The term ‘Contemporary Art’ refers to art being produced now and using a variety of forms, styles and media. Modern Art’s hallmark was using line and color in painting to move away from a naturalistic goal and towards an eventual extreme of minimal abstraction; form and space were used in sculpture towards similar ends. ‘Contemporary Art’ is post-modern in the sense that it moves beyond both the timeline of Western Art History from Renaissance naturalism to modern abstraction where line/color is the subject matter and instead into something which both brings back a multiplicity of themes, subjects, styles and media but also looks towards the ‘global’.

To be at the center of Contemporary Art means to be in a place where the visual arts, new media, film, architecture and design all figure prominently and thrive; a brief look at leading art magazines such as Art in America or Artforum suggest a fluid world of all of these with a healthy dose of fashion and style thrown in. New York City still figures prominently in any discussion about the Visual Arts and what is happening now- a place it has held on to since at least the end of WWII when Paris was recovering from a German occupation. London has had a vibrant scene for decades and is an international crossroads for both artistic production and larger exposure. Other factors which make a city a hub for Contemporary Art include a functioning commercial gallery scene along with (and often at odds against) a thriving and organic counter-culture as well as a breadth of institutions, museums and art schools.

Istanbul remains a destination for the Muslim world because of its location, accessibility and beauty. First impressions of the city’s visual landscape reverberate minarets and water and there is a collective pride in visiting historical mosques, palaces and streets that remain so breath-taking.

Certain trends continuously present themselves when discovering a city’s art scene. Artists are constantly looking for affordable work spaces and access to grants and funding. Smaller cities can be alluring in this regard as can industrial areas and third-world metropolises. Cities with large art scenes like Toronto, Canada have a number of galleries, journals and magazines (and of course artists) but have little to offer that is radically different in terms of culture, perspective and history. European capitals are dynamic but remain places mostly for the local population of artists, writers, filmmakers and designers to work and live in (Berlin may be the exception). Indian cities Bombay and Delhi are important art centers in Asia – but remain too closely tied to the art market and the buying and selling of works in auctions and galleries (and hence a hesitation in sponsoring, producing and promoting more cutting edge media).

Looking for Contemporary Islamic Art

What is often described as ‘Islamic Art’ stretches dynasties, periods and huge swaths of the globe. Key periods in art and architecture include Andalusian, Persian, Ottoman, Mughal and Deccani. Patterns and design in architecture create an aesthetic of non-representational abstraction where line, color, space and light are used to signify the infinity of Allah’s universe. This can arguably be described as ‘Modern’ hundreds of years before 20th Century Western Modernism.

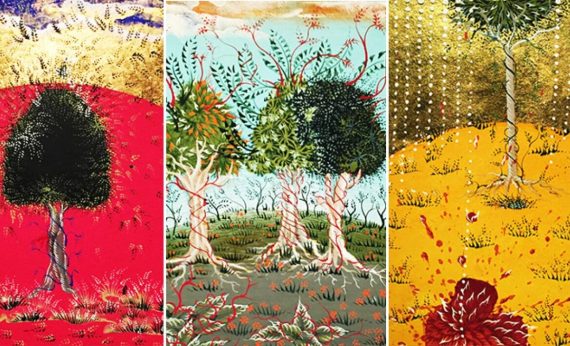

Miniature painting gives prominence to a form of visual story-telling where the narrative unfolds through saturated colors and flattened landscapes – where characters are part of a larger message, theme and universe that mixes history, fiction and fantasy. Simpler, looser rendering gives characters a role as part of the landscape rather than as the sole representational focus of the painting (as was the case in European painting of the time).

One of the interesting developments in cinema over the last 25 years was the rise, critique and then canonization of the Iranian ‘New-Wave’. What was first described as a cinematic ‘anomaly’ was later endlessly written about in the context of politics and the need to ‘veil’ creative expression; now some of the key figures from that period (eg. Abbas Kiarostami) are firmly cemented as key directors in the history of cinema and a larger breadth of Iranian films covering diverse subject matter and genres are released and distributed globally. This has influenced many non-Western filmmakers (such as in India or Turkey) with a renewed interest in shooting on location in smaller towns or villages and the search for an authentic naturalism in the performances and settings. However the full influence of the Iranian ‘New-Wave’ is still being felt in the formal approach to traditional or classical Islamic sources.

Istanbul needs dedicated National Art and Film Institutes that are portfolio driven (rather than grade and exam based) and which move beyond simply being a department in a University.

Iranian Cinema is important as a new form of Contemporary Islamic Art for a number of reasons; the subject matter which reflects a post-revolution Islamic society is something often cited but it’s actually the formal approach – one that mixes aspects of self-reflexive documentary, Persian poetry and miniature painting while shooting on location to create a new style both remarkable and influential.

Recommended

Istanbul City of Culture 20..?

Historic, dynamic and energizing – Istanbul has managed to preserve much of its Ottoman architecture and has major areas which are designated as UNESCO world heritage sites (Sultan Ahmed complex and Suleymaniye quarter). Compared to other cities of the Islamic world buildings are relatively well-maintained and respected (although Republican period ‘modernization’ was a balderdash for many functioning fountains and Mosque complexes and more recently some well-intentioned renovations for the cultural events of 2010 feel rushed). By comparison cities such as Old Delhi or Hyderabad, India which were once jewels of Mughal and Deccani architectural splendour have disintegrated through a combination of neglect, pollution, encroachment and politically motivated destruction.

Istanbul remains a destination for the Muslim world because of its location, accessibility and beauty. First impressions of the city’s visual landscape reverberate minarets and water and there is a collective pride in visiting historical mosques, palaces and streets that remain so breath-taking.

The International Istanbul Biennale remains one of the major Contemporary Art events in the world and yet there is a major disconnect between the style of work shown and the city itself; it could be shown in any place (New York City, London, Toronto, Berlin) and has not in any significant way reconciled itself with the Ottoman-Islamic heritage, culture and art that surrounds it. The last two Biennales have been criticized as too political, too text-driven and too obscure by the very International Art World that feeds it (eg. New York based publications); the city’s Biennale is more ‘Western’ in its approach to Contemporary Art than the West itself.

The notion of Contemporary Islamic Art is challenging for many people. For some the very word ‘Contemporary’ has certain connotations of vulgarity or obscurity; for others the term ‘Islamic Art’ is politicized.

On the other side of the divide there are pockets of local exhibitions which display Calligraphy and other traditional arts such as miniature painting; these are often held in municipality-run cultural centers and exude an amateurishly derivative mix of mediocre skill, poor lighting and installation and an absence of any concept. The work displayed is often done as a hobby on the side and often seems honored simply because the viewer admires its ‘Islamic’ aspirations rather than on the merit, quality or idea behind it.

Istanbul needs dedicated National Art and Film Institutes that are portfolio driven (rather than grade and exam based) and which move beyond simply being a department in a University. Specialized departments that present visual art, design, film, fashion as parts of the same world as well as a reconciliation between traditional crafts and techniques and contemporary approaches to Art which highlight the importance of concept and self-expression. A move beyond calligraphy as the only authentic ‘Islamic Art’ – an opinion which has become increasingly prevalent through narrow perspectives being given wider platforms – is also necessary.

The notion of Contemporary Islamic Art is challenging for many people. For some the very word ‘Contemporary’ has certain connotations of vulgarity or obscurity; for others the term ‘Islamic Art’ is politicized. Beyond the borders of Turkey a global embrace of all the quality Islamic Art and Architecture that exists (including examples like miniature painting, patterned objects, fountains, tombstones and mosque and palace interiors) and the preservation of this work alongside an equally great thirst to create, build and express new and innovative ideas that branch out from this heritage is a noble objective – and one that is already starting to happen.