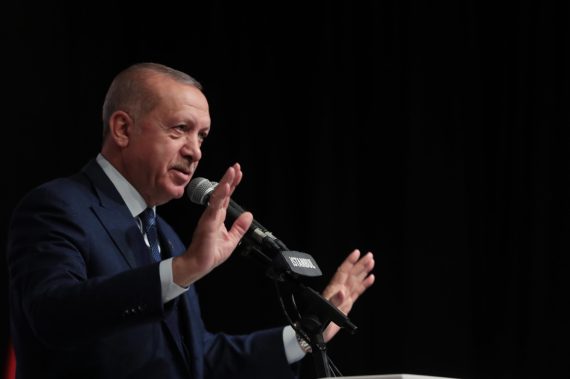

When Recep Tayyip Erdoğan became the Turkish Prime Minister in 2003, it was immediately clear that a new era had dawned in the country. Whilst Erdoğan’s AK Party had won a majority of Turkish votes, thus giving them a mandate to form a new government, many in Turkey remained sceptical as to whether Erdoğan would be able to deliver on the promises that he and his early political partner Abdullah Gül had pledged to deliver. Likewise, other Turks were skeptical over whether the social change that the new AK government would bring would be positive or negative.

Inversely, the rise of Erdoğan was widely praised throughout the west. Erdoğan’s pro-business, pro-economic growth, pro-trade and pro-enterprise stance was seen as a welcome development among western businessmen and financial markets who had long spoken of Turkey’s untapped economic potential but who could scarcely bring themselves to deal with the overly regulated and stagnating economy that unfortunately defined Turkey through much of the lattermost decades of the 20th century.

Erdoğan was likewise praised for injecting fresh energy into the overall democratic atmosphere in Turkey by challenging not just the electability of the legacy CHP, but in challenging the lethargy and complacency that often serves to define legacy parties long after such a party’s heroic founder had died.

The rise of Erdoğan was widely praised throughout the west. His pro-business, trade, and pro-enterprise stance was seen as a welcome development among western businessmen and financial markets.

In terms of his foreign policy, Erdoğan’s early years were defined by an enthusiasm to build on Turkey’s already strong relationship with the European Union with an aim to eventually join a bloc of nations which unlike today was defined by optimism and economic growth between the turn of the 21st century and 2008.

Finally, Erdoğan’s democratic credentials combined with his open embrace of Islam was often praised by western leaders looking for a major international figure to point to in order to illustrate that the increasingly widespread post-9/11 theory that Islam and democracy are uniquely mutually exclusive is false.

Whilst Erdoğan and the AK party have not changed in their ideology and overall mission for the country, western powers have changed both internally and in their perceptions of a remarkably consistent Turkish government and society.

Things began to change when Gülenist terrorists grew determined in their mission to overthrow the legitimate authorities in Turkey beginning in 2013. Because Gülen was able to use his wealth to influence liberal western mainstream media, the same Erdoğan hailed for being a pro-business Islamic democrat within the framework of an open and tolerant modern society was transformed into “the villain next door.”

For ordinary Turks the Gezi Park provocation was an event designed to sow social discord at the behest of foreign based actors including the U.S.-based Gülen and the infamous George Soros.

Recommended

For ordinary Turks the Gezi Park provocation was an event designed to sow social discord at the behest of foreign based actors including the U.S. based Gülen and the infamous George Soros. However, rich and powerful western based individuals like Gülen and Soros were able to use their influence over the corporate western media to portray the Gezi Park provocateurs as “peaceful democrats” even though subsequent court records from Turkey have proved otherwise.

As the EU economy slowed down, Islamophobic sentiments continued to move from the periphery to the mainstream. As is often the case in times of economic downturn, the European extreme-left also became more emboldened in their calls for a new political consensus. In respect of how this effected Turkey, the otherwise opposed groups of the Islamophobic right, the Soros manipulated liberals and the extreme left, all ended up perversely agreeing on their hatred of Erdoğan’s Turkey. For the Islamophobic right, Erdoğan’s position as the world’s foremost political champion of the rights of Muslims throughout the world was seen as a threat to a worldview which seeks to portray Muslims as unilaterally wicked and Christians, secularists and Jews are uniformly innocent.

For the Soros style liberals, Erdoğan’s refusal to allow his nation’s internal affairs to be subject to malign foreign interference was a trigger for such groups to accuse Erdoğan of being some sort of anti-democratic human rights violator even though the terrorists he arrested threatened not just Turkey but the wider world. A strong argument can also be made that traditional free speech is much heathier in Turkey than in the increasingly censorship happy European Union. Finally, the European far-left that had always had a perverse soft spot for the PKK terror organisation found a strange comrade in the form of the U.S. military which, beginning under Barack Obama allied with the Syria branch of the PKK, the YPG in the Syrian conflict.

At the same time as western powers became increasingly strained in their relations with Turkey, Turkey itself continued to make new partnerships abroad. Under Erdoğan, relations with neighbouring Iran and nearby Russia improved greatly in spite of external actors attempting to prevent both whilst under Erdoğan, Turkey signed up to the international game changing Belt and Road initiative which was introduced by China in 2013.

More recent years have seen Turkey expand its economic and cultural connectivity throughout Africa with investment projects and visits by major Turkish officials becoming ever more common from South Africa to Sudan. Turkey has also come to engage ever more with the dynamic and economically vibrant Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN). Relations with Pakistan likewise continue to remain strong and within this context Islamabad has formally invited Turkey to participate in projects related to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor which aims at expanding Pacific to Afro-Mediterranean trading routes.

For the Islamophobic right, Erdoğan’s position as the world’s foremost political champion of the rights of Muslims throughout the world was seen as a threat to a worldview which seeks to portray Muslims as unilaterally wicked and Christians, secularists and Jews are uniformly innocent.

This has further led to western antagonism against Turkey not because of any Turkish maleficence against the west, but because of America’s particular tendency to exert its economic authority in order to prevent other countries from developing a multilateral foreign policy. As Turkey is among the most prominent and strong nations seeking to balance relations between the major powers of the west and those of Eurasia, Ankara has been singled out for specific harassment, particularly when it comes to Turkey’s decision to buy S-400 missile defence systems from Russia. Thus, Erdoğan is now hated in certain western quarters not in spite of, but because of his consistency and his unwillingness to compromise from a position of weakness.

In this sense, the same qualities for which many western leaders and analysts once praised Erdoğan are those which now earn him excoriation from the west. Erdoğan’s willingness to emphasize Turkey’s democratic, Islamic and modern traditions simultaneously, his championing of a high growth strategy for the economy, his willingness to engage in unique win-win agreements with partners to the west, south and east and his ability to transform Turkey from a place where the world came to admire history to a place where the world now comes to admire the present and future, remain his defining characteristics.

One must remember though, just because western leaders and policy advocates have changed their mind on Erdoğan, for most of Asia, Africa and even Latin America, Erdoğan and Turkey’s star continues to rise whilst many are questioning whether the decline of the west is temporary or permanent.