Humor magazines are beyond an entertaining fantasy or stereotypical thought. Instead, they are essential instruments of cultural and political production and distribution. Especially caricatures, not only as intellectual reflections of everyday life, are also ideological and manipulative fiction toward shaping public opinion. On the other, the point of whether humor is totally against the power is considerably paradoxical. This article, in this sense, focuses on the cliché-like discourse in the context of the modern Turkey and by dealing with some popular magazines such as Leman, Gırgır, Penguen and Uykusuz. Moreover, the notion of the opposition is examined through some crucial breaking points experienced particularly after 2002 when AK Party came to power for the first time.

Recommended

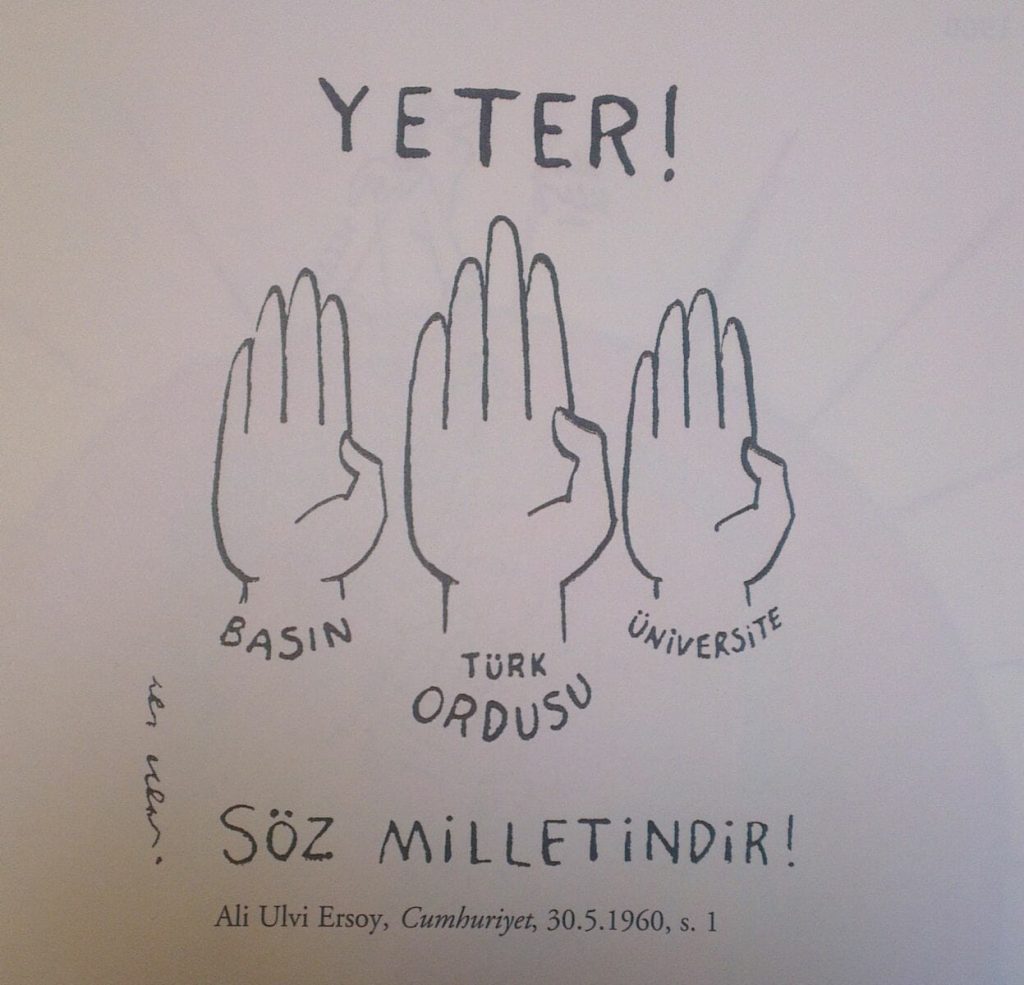

Ali Ulvi Ersoy’s caricature published on May 30, 1960 in Cumhuriyet newspaper, following the military coup of May 27, 1960 and dedicated to the Grand Turkish Army (Büyük Türk Ordusu).

As a result of the rigid perspective, all these magazines provided an intellectual basis for the execution of Menderes, the legitimate president. Humor magazines, as a representation of cultural hegemony, have moved in concert with the junta in modern Turkish history that is full of military coups and conspiracies, so much so that they produced fun and erotism-oriented publications in spite of socio-political conflicts between 1960s and 1990s. Although many scholars and politicians were murdered by unknown assailants especially in 1993, the magazines generally ignored the essential question. What is more, the 1997 military memorandum was approved by caricaturists. The hegemony war between conservatives and seculars, between nationalists and socialists, between traditionalists and reformists turned into a tense cultural segregation after AK Party was founded and Erdogan became prime minister.

Before and After 2002

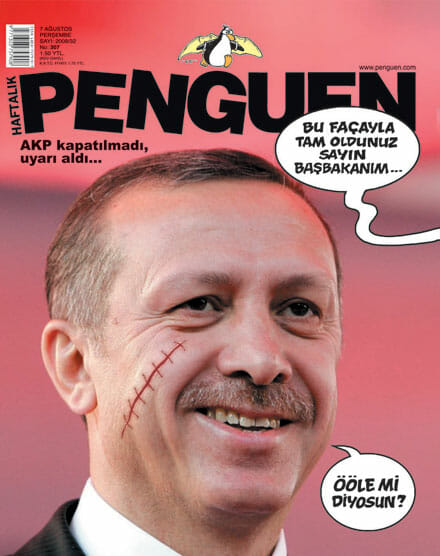

Humor can understandably be an ideological and subjective providing that it makes opposition in a principle sense. The basis of the principle should be conscience, justice and courage. However, humor publications in Turkey are biased, unfair and tutelary; so much so that they have supported the military coups experienced since the late Ottoman era, also that they felt free to describe the ousted leaders as animals on account of supporting the official authority based on nationalist Kemalism. Not only Abdulhamid II, also Adnan Menderes, the elected president, who was executed by hanging was harshly criticized by humorists. They did not utter a word about militarism. Further, same attitude was continued in March 12 (1971), September 12 (1980), February 28 (1997), April 27 (2007) and even in July 15 (2016). In fact, the figure of Erdogan in the periodicals accompanies previous ousted or, at least, ‘chastened’ leaders. He was drawn as monkey, camel, cow, frog and snake and depicted as bigoted and vulgar character. He was ‘orientalistically’ associated with Hitler. Also, the AK Party supporters were stereotyped as ignorant and amorphous mass. Electoral system and even democracy was questioned whenever AK Party won the elections.

Penguen Magazine cover dated August 7, 2008. The magazine summarized a top court’s decision not to close the AK Party as “AKP was not closed, but warned” with a smiling picture of then prime-minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan with a scar on his face. The court decision did not please Penguen magazine, which always represents itself as democratic.

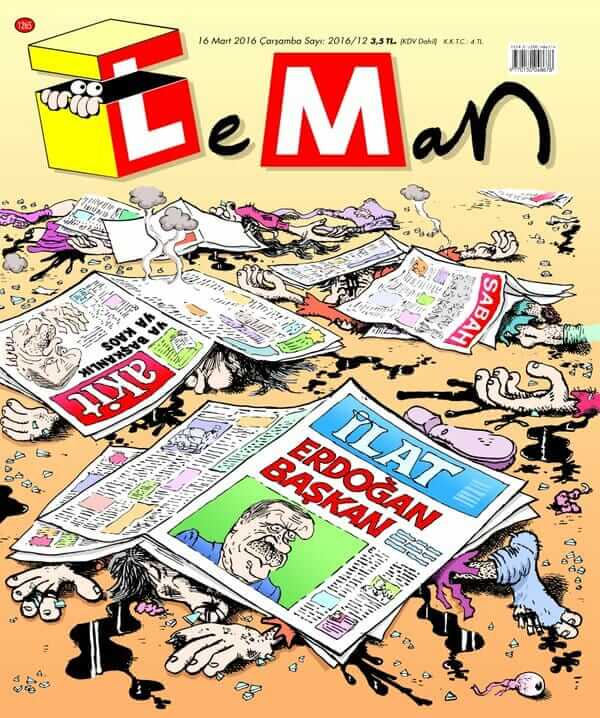

As for the political opposition in Turkey, they were instead sympathized. Terrorist groups such as PKK, DHKP-C and TAK were never criticized by leftist humorists dominating this field. The term “terror” was linked only to Erdogan, the State and the government. The unprincipled view can be conceptualized as “Tayyip-phobic humor”. Today, humor without Erdogan is almost impossible. The opposition made by humorists concentrated merely on his “evil” existence. He is known as the crux of every problem in Turkey, in Middle East and even in the world. The humorists, who define humor as cliché-breaker, produce rude and rigid clichés ironically themselves. What is more, some of these are indisputably Islamophobic. The magazine covers that are intolerant about religion, tradition and pedagogy are full of ‘ugly’, ‘repellent’ and ‘terrorist-like’ Muslim types. The language of the publications is mainly slang, swearing and humiliation rather than irony and lambency.

One of the deadlocks of humor publishing, not only in Turkey also in all over the world, is the ambivalence between censorship and freedom of expression. Humorists generally tend to reduce the freedom into unlimited liberty and to define the censorship as restriction of freedom. However, just as freedom does not refer to a free hand, censor is not antithesis of freedom. The concept freedom that becomes vague and gets more complicated each passing day in the contemporary culture is paradoxically is positioned in an absolute positiveness, therefore its destructive mission in the context of consumption-based worldview is ignored in some way. According to the overall impression gaining from the statements made by humorists, AK Party has dominated humor magazines and sued for damages, so much so that Turgut Çeviker, a humor historian, describes AK Party era as the most radical period in which caricaturists are suppressed and humorists are marginalized. However, considering the cases, it is easily seen that almost all of them were dismissed in favor of caricaturists. Moreover, these cases were somehow seen as a resistance mark against the political power.

Leman Magazine cover dated March 16, 2016. The cover portrays the Ankara bombings of March 13, 2016, which were claimed by the TAK terror organization, a branch of the PKK, yet the magazine redirected the blame on Erdoğan and connected the issue with the debate on presidentialism.

Humor magazines that have taken a stand against the AK Party government in every crisis and that have seen Erdogan as responsible in all local or global trouble categorize and discriminate the society. On the one hand they underline the importance of peace and solidarity in interviews, but on the other hand, with their works, they provoke the differentiations and cultural tectonic faults of contemporary Turkey as Turks and Kurds, Alevis and Sunnis and, seculars and conservatives. In this respect, we can conceptualize this non-principle approach as a “humor dictatorship”. As an indication of this approach, although they highlighted Berkin Elvin and Ali Ismail Korkmaz who lost their life during the Gezi Park protests, they said nothing about Yasin Börü and Serap Eser who killed by the PKK and its extensions. Similarly, they frequently dealt with Kobane, but never Aleppo.

Without doubt, most humorists in Turkey are not elite but elitist and they are away from the real problems of the society in which they live. Throughout the history of the republic, they have satirized civilians rather than elites, so much so that they have taken active roles in legitimizing the military tutelage against democratic regime. They have been more rigid and bigoted than even religious dogmatism despite the fact that they define themselves as creative, cliché-breaker and reformist. Hence, in the magazines, while facts give their places emotion-based ideologies, opposition turn into vulgar aggression. Since Tanzimat era, political power and cultural power are separate and even vis-a-vis. Therefore even if governments are determined by elections, the Power is mostly at the settled elitists’ hands, and more interestingly, although humor magazines that describe themselves as ‘unofficial weekly’ reproduce the discourse of those who see themselves more equal than others. In other words, just as humor magazines in Turkey stand in the heart of official history and ideology, they are not dependent upon, for and together with the society.