Turkey has been witnessing proliferation of the traditional architectural forms as the country reconciles with its Ottoman past. The early republican regime took radical steps during the 1930s and 1940s to systematically downgrade and erase the cultural memory inherited from a more cosmopolitan and sophisticated Ottoman heritage. This caused a deep controversy and made a traumatic impact on the Turkish society. The persistent war on culture and the discursive hegemony of the republican elite produced lots of tragedies with which the people of Turkey still have to face. In fact, rediscovery of the Muslim heritage was a general phenomenon all over the Muslim world from East Asia to North Africa since the 1980s. However, this development halted in Turkey in the 1990s due to the secular establishment’s suspicion of conservative masses and their traditional values. Heavy hegemony of the secularist elite over “culture” only recently tended to be lifted and the past has been relatively emancipated from monolithic readings of history, a great opportunity for enhancing democracy and cultural diversity in Turkey.

Reflections of the current process of reconciliation with history can be seen in different spheres of life from the shop names to architectural forms of public and private buildings, ever growing interest in the television series based on historical figures or periods in addition to the TV shows hosting popular historians and discussing popular historical subjects. Even the daily language, which is slowly being occupied with Ottoman-Turkish words, rediscovered and occasionally reinvented with a sense of amazement as well as amusement. No doubt, this is not a refined or a painless process which creates its own set of problems like the production of kitsch or generating not always accurate reflections of identity based on the revisionist readings of the past. However, conservative religious circles have lately begun to question their perception of history, which is overall torn between exalting and disparaging. A popular Ottoman historian has baldly claimed “history is poisoning us” in a monthly journal called Lacivert referring to the current problematic interpretations of the past. Another author in the same journal complained the superficial appropriations and understandings of the past that are both likely to waste a lucrative opportunity and thus preclude proper contemporary reconfigurations addressing the present needs and expectations. The tension and competition between and within secularist and conservative “quarters” over culture and history will apparently continue in the following decades to define the public space in Turkey and the architectural forms and preferences will constitute one of the most visible and hot topics of this debate.

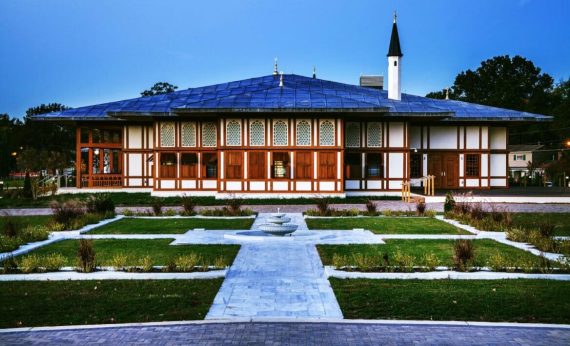

In this broad socio-political framework, one should analyze the architectural choice of the Diyanet Center of America in Maryland which is being inaugurated this weekend by the participation of the Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. The center is built on 60,000 square meters, half of which is covering the constructional area. The huge project consists of a conference hall, library, cultural center, a mosque with a capacity for 1,500 people (3,000 including the courtyard, being the largest mosque in the U.S.), a fellowship hall including a restaurant, cafe and shops, a double Turkish bath with its pool and indoor sports hall, a guesthouse, a state-of-the-art Museum of Islamic Civilizations, a neighborhood consisting of Turkish houses, a Turkish-Islamic garden, open sport areas, picnic areas, fountains and parking area for 400 vehicles.

The architect of this huge complex is Muharrem Hilmi Şenalp who is known with his great amount of knowledge and expertise on as well as his firm commitment to the classical Ottoman architecture. His office, Hassa Architecture, was named after the Mimaran-ı Hassa Ocağı (State Architecture Corps) which was an official organization founded by the Ottoman Empire and that the corps was responsible for the architectural design along with undertaking the construction projects. Şenalp’s symbolic reference is not designated for a synthetic namesake but undoubtedly has some essential characteristics. His devotional determination in reproducing classical Ottoman architectural forms while designing today in the twenty-first century is due to a deliberate identity quest which was not in the slightest imposed or supported by the construction material, concrete and steel. The Hassa Architecture manifests its objective in their website, epitomizing the project as “an opportunity to represent our deep-rooted millenary civilization by handling it as a whole with its overall course and originality.” Therefore, this experiment actually stands out as a bald manifestation and perhaps a radical response to the contemporary post-modern and deconstructivist architectural currents which one may fairly criticize for their decontextualizing effects through disregarding the existing architectural landscapes and suggesting a definite rupture from the past.

Recommended

The architectural designs of various constructions in the Diyanet Centers of America can be traced back in the earlier works of Şenalp. For example, the mosque in the Center resembles very much to Ankara Subayevleri (1996), Tokyo (1993-2000) and Berlin Sehitlik (2004) mosques from an external glance. Likewise, the Turkish houses and other buildings with similar functions bear a clear resemblance to the Küçük Çamlıca Kiosks (1998) and to certain buildings in the Prime Ministry Ottoman Archives Complex (2009), both in Istanbul. The architectural ancestry of this choice recalls a more substantial question that is to what degree such designs can be regarded as up-to-date examples of historicism or anachronism. A great number of pictures generously shared by the Hassa Architecture in their website recalls the Ottoman pavilions in the sumptuous World Fairs of the late nineteenth century, a time period in which eclecticism and, from a critical perspective, historicism was predominant all over Europe. One may also feel uneasy about the relationship between these architectural forms and the place where they were built.

However, from one perspective, Şenalp’s approach can be regarded one of the several legitimate architectural choices and innovative at least as much as the postmodern and deconstructivist architectural experimentations. Şenalp’s architecture follows the principle of renewal from within the tradition, which means that the design, freed from virtuosic concerns, communicates with the forms of the past and associates them through new configurations with due respect to their proportions. It uses the old technics and craftsmanship but also benefitting from new materials and expertise. Although having clear predecessors, inlaid doors, for example, are not direct replications of any existing historical doors. Instead they are original designs fashioned by the living craftsmen adding their own minimal stylistic contributions and even more vaguely addressing the “modern” taste as well. Şenalp’s recently inaugurated Marmara University Theology Faculty Mosque in Altunizade Istanbul demonstrates his openness and perspective regarding the new forms of architectural designs. The mosque looks entirely “contemporary” but at the same time full of references to the past. In fact, the dome of the mosque, being the most impressive part of the building, is inspired by an existing traditional form, called kırlangıç kubbe which can be seen in some public and civil architectural examples in Erzurum.

Beyond doubt, the architectural designs of Şenalp, whether traditional or contemporary, is a deliberate manifestation of a quest for identity of its architect and of its sponsors. This approach reinterprets the traditional forms in such a way that it is related to the past, history and memory. This is one architectural quest for identity, along with various other approaches, and a response to the globalizing world in which values are being homogenized and social memory is altered through a structural imposition of decontextualized spaces. A visitor of the Diyanet Center in Maryland notes that the mosque is already filled with Muslims from various backgrounds, all gathering every week for Friday sermons and excited by the scene that makes them feel “at home”. With respect to the contemporary discussions in Turkey, it seems that the public space, though still on its long way, is becoming more pluralistic in terms of the cultural manifestations of Turkey’s past in present.