When a team at the Scientific Studies Association (İLEM) designed a clock with Ottoman features, it sparked a debate over the object’s place in today’s society as well as history. Lutfi Sunar, a Sociology professor at Istanbul University who lead the team, speaks with Dr. Faruk Yaslıçimen about the clock, and the larger lessons one can learn about how society, the state, and individuals perceive their place in a history that is often self-manufactured.

Firstly, I would like to thank you for allowing me to hold this interview with you. I want to talk to you about the Turkish society’s perception of the past, the society’s relations with it and how the past is reproduced and consumed. If you please, let’s start with a work of your institution and its background. You had prepared a bookmark for the tenth anniversary of the Scientific Studies Association (İLEM) in 2012 and there was a design of an old clock on it. In time, this visual started to be circulated on the Internet as the “Ottoman Clock” and even become a product. What was your initial intent?

Initially, we wanted to design a bookmark looking like a clock, which had several of the most prominent concepts of the Islamic civilization. Selecting these concepts took some time. Eventually, we tried to place the concepts hierarchically on the clock; however, it was not possible, as we were unable to establish a hierarchy between the concepts. Depending on perspective, a hierarchically superior concept could also be perceived as an inferior when compared to others. Therefore, we decided to place representations of the concepts on only the numbers 3, 6, 9, and 12. We placed “Hakk” (God or the Truth) on 12, while placing the concept of “human” on 6, establishing a hierarchy on the vertical axis. Similarly, we placed “irfan” (knowledge or wisdom) on 9 and “ahlak” (morality or principles) on 3, establishing a hierarchy on the horizontal axis. So we accepted these as the vertical and horizontal axes of science and knowledge. We placed certain concepts like “justice” and “comprehension” in between these. This was a gift prepared for the 10th anniversary of İLEM. It was a plain and simple bookmark. Behind the bookmark, we inscribed these details along with the name of the designer. Yet this visual spread on the Internet and gained new meanings besides the one we attributed to it. It was seen as an Ottoman clock.

Had you named this visual?

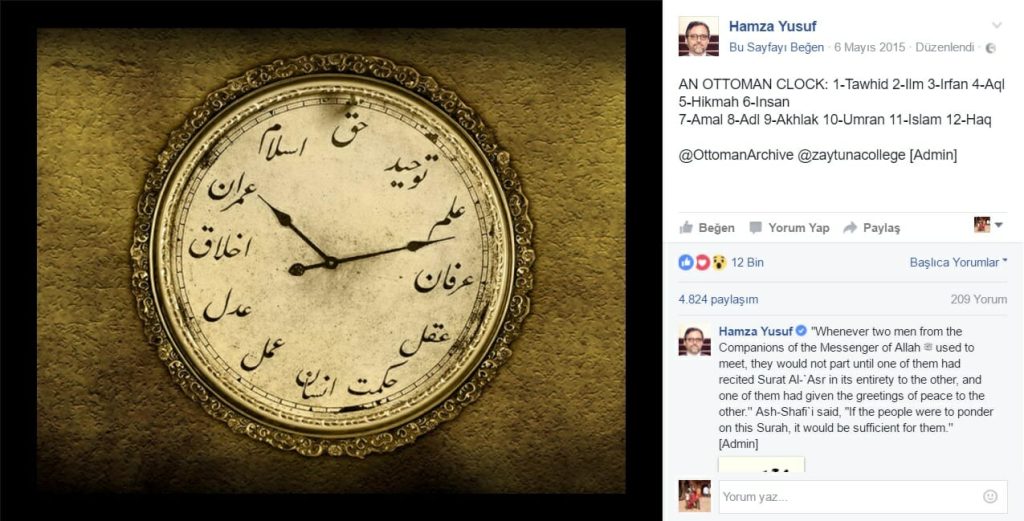

We hadn’t named it. It was just a gift for the 10th anniversary of İLEM. After its perception as an Ottoman clock, people started to see it as “a monument to the value attributed to science by the ancestors.” Even now, when you Google “Osmanlı Saati” (Ottoman Clock), you find the bookmark we prepared. Eventually, this visual was made into a watch, a clock, t-shirt and such. The people started to see it as their own. Moreover, some renowned figures shared the visual on their social media accounts and sparked discussions, some of which were very interesting.

Could you provide an example?

Of course, for instance, when Hamza Yusuf shared this visual as the Ottoman clock on Facebook and Twitter, a serious debate began on whether the clock was Ottoman or Iranian. A follower of his was saying that this could never been an Ottoman clock, but it could be an Iranian one. We had used the ta’liq script to write the concepts and Ottomans didn’t use this type of script when copying the Holy Quran. Iranians predominantly used it. However, the reality was different; the calligrapher we had an agreement with knew ta’liq and we didn’t have much time for its preparation, we just thought that it was only a bookmark and the details aren’t that important.

But ta’liq was also used extensively by the Ottomans. They had also used this script in their official correspondences.

Yes, it was being used by Ottomans in their official correspondences and literature, along with other fields. Nonetheless, as Iranians used it more commonly than the Ottomans, for instance even in the Holy Quran, Hamza Yusuf’s follower was not that wrong. Looking at it from the perspective of historical methodology, if you had found such a visual in a book, you would first think that it probably belonged to Iranians.

So, what is the current condition of your clock?

It seems like a new product that is popping up every day and it’s continuously being marketed with new marketing strategies. Our bookmark became a part of pop-culture.

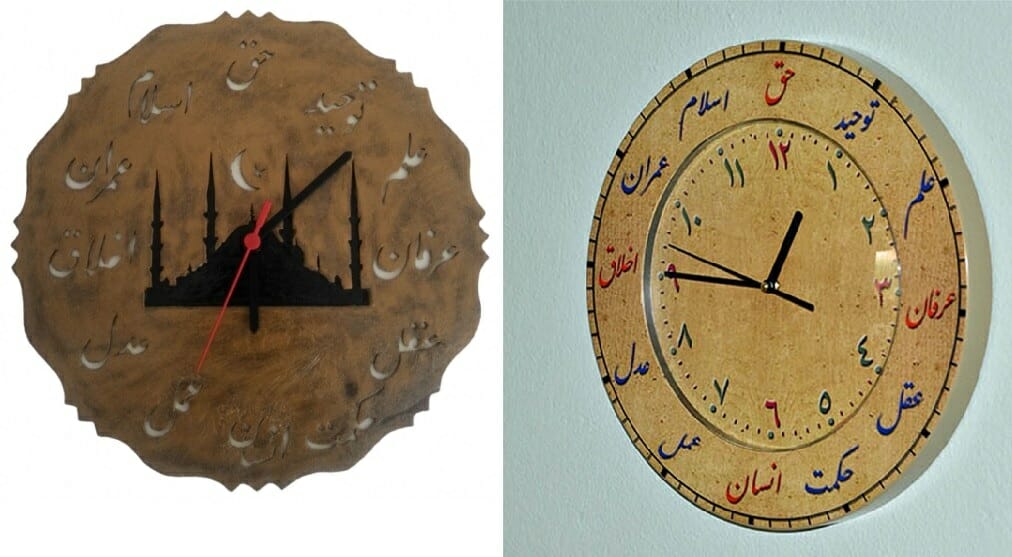

Was a real clock made out of your bookmark design?

Of course, there are even various versions of it. Certain firms are making these clocks out of wood or iron. Moreover, the designs of the clocks started to evolve. It created its own neoclassicism; the colors and shapes started to change. It’s become a truly popular item. We are also seeing that it’s evolving further with special orders.

Are you forcing the firms to pull these clocks from the market?

We’re unable to do so. At first, we chose to send cease and desist letters to these firms through the notary. Everything aside, it is a work of art and intellectual property. It’s an original design, which was designed by a designer. Therefore, it’s about protecting our rights. We didn’t want this to spread for this reason. And, it’s spreading a false kind of idea. Then, I realized that history consists only of these false ideas. Some of the firms we sent cease and desist letters pulled their merchandise from the market. A couple of them apologized, but, as when we saw an unstoppable culture of imitation in the country, we stopped pursuing it.

I have to object as a historian. Let’s start from the beginning; a product, which is deemed good, beautiful or faithful to history, is made. It’s not being made in the name of history; it’s produced for today with a script that isn’t being used in our daily lives. Then, this product becomes a part of the social belief and it becomes spread due to its historical references. Rather than fakery, we are talking about what the society believes in. Doesn’t history have this kind of a dynamic aspect? History is something that is believed in. So, it’s more than just the recollection of what happened in the past; it’s like a poem of what we believe has transpired in the past. Isn’t that right?

As you know, Ibn Khaldun expresses that rulers, scholars, illiterate people and the masses alike have an interest in history, while he talks about history as a science. “The people and even the careless want to know history,” he says. History is an intriguing subject, but why? It actually serves as a means to provide a meaning to today, to provide security, while allowing us to find our way to the future through the events that transpire. Ibn Khaldun calls this “the history of commoners.” On the other hand, he talks about another form of history which focuses on the causes of events appealing to the scholars. Isn’t history as popular in Turkey? There are history pages in newspapers, and there are primetime TV programs. Moreover, there are radio shows on history and the politicians constantly make history everyday; there are even some which still fight over an event that has transpired 300 years ago. Therefore, history is never-endingly current. After the said events, I started to think once more on this subject. Why are the people interested in the past? Why do long gone events bother the people this much?

If we’re talking about history in Turkey, the identity problem can also a factor, right?

Yes, I think it is both about security and identity problems. It’s an ontological state and identity is affiliated with it. History is a suitable conduit for one to position himself/herself in the world.

On the other hand, you came up with the idea for this bookmark that looks “historical”.

That’s correct. This reveals our subconscious. For instance, why didn’t we create a modern bookmark, but designed a bookmark with Islamic concepts on it? Nevertheless, I can say that initially it didn’t have any historical meaning for us.

Yet, you didn’t use the current Turkish alphabet, but the Ottoman Turkish alphabet.

A phenomenon we believe to be ahistorical or not necessarily historical may be perceived as historical by the society. Today, anything related with Islam is considered as historical by people. However, I think that they also believe Islam has become outdated, but it could still be made relevant by updating certain aspects of it.

Here, it appears to me that you are shaping how it is going to be understood by the society with your preferences. Firstly, these concepts belong to the Islamic civilization. It’s your preference and it corresponds to your position in semantics. Then, you decide to make it in Ottoman Turkish. These concepts were mostly created and used at that time. By using ta’liq script, which was again used by the Ottomans, you connected the text to a wider context. Thus, all of these are references to the past and I believe it’s only natural that people perceive it as a part of the past. Could this be a result of you having a similar background while creating the bookmark?

The real question here is do the people perceive other things in a similar way. There is the idea that the reality of certain historical figures might be different. For instance, people are watching the TV series Diriliş Ertuğrul today. There is an idea about Ertuğrul; however, his very existence is being debated by historians. Again, the people are watching Game of Thrones, yet they know that it’s fiction, even though it replicates certain historical eras and has characters inspired by historical figures. On the other hand, Diriliş Ertuğrul is a series about a figure that is believed to be historical and the series attributes certain contemporary concepts to this reflected history. On this subject, we can say that in our imaginations many of the past events are associated with today’s situations.

For instance, the [early 18th Century] Tulip Period is perceived as an era of immense entertainment, indulgence and pleasure which caused the Ottoman Empire to regress. Even though the reality is completely different, this image was created during the Republic era to create a cause for the fall of the Ottoman Empire. This image was needed at the time and, thus, it was created.

The shift in the image of the Tanzimat period is more interesting. While it was first seen as an act of treason by the early Republic scholars, later it was praised as the first steps of Ottoman modernization.

Similarly, the images of Abdulhamid II are all baseless, as they are fictitious to an extent that could deprive Abdulhamid II of his historical character. Left-wingers, right-wingers, Kemalists and conservatives all have a fictitious image of the Sultan.

On the other hand, all of these images are evolving as the elements of identities shift; different aspects are brought to the fore and discussed. The adventure of this clock made me think about how we can differentiate fictional narratives from reality.

It’s known that the bourgeois class in France, which lacked an aristocratic background, created their own background stories. This has a fictitious aspect. “The past is static, but the history is dynamic” or “the past is certain, the history isn’t”, they say.

I believe that history has some aspects which are certain. I believe that the causes behind the sequences of events and the knowledge extracted from the abstraction of how the events in the past took place have more certain data. It’s mostly perceived as if events represent the reality, while their interpretation is fictional; however, if a conclusion on history is reached through a meticulous process of distillation, I believe it’s more a part of the reality and definitely more helpful in understanding what has transpired.

Let’s return to the subject of society and history. Do you refer to your own clock as “Ottoman clock”?

Yes, we’re referring to it in that way now.

There are many imitations of your clock out there. We see a similar trend in the shop names, as well. We’re hearing that people are creating new phrases in Ottoman Turkish, looking at an Ottoman Turkish dictionary or consulting people of letters for the names of their shops. Analogous to this, we are seeing attempts in architecture to connect with the past, resulting in both meaningful and superficial examples, along with being pastiche. The truly exemplary products, on the other hand, aren’t that widespread and as famous. Today, the past is something that we both produce and consume. What is the future of this need?

For some, it seems like the society is reconciling with history; however, I believe it’s associated with the search for identity and security. Especially during times of great social changes, society believes that their identity is in danger and the elements that make them are fading away. As I said, this is a belief, not knowledge.

Wasn’t this always the case?

This belief always exists; yet, it becomes accentuated during times in which changes are swift, political tensions are high and there is a fear for survival. There’s an inclination in the society towards creating an identity to guarantee its existence. For instance, the spread of Nazism in Germany after WWI is a great example for this inclination. Similarly, the emergence of German romanticism after Napoleon’s invasion is another example. When survival is at stake, the society looks for something to hold on. This is sometimes religion. As religions have roots in history, this paves the way for referring back to history. This leads to holding on to certain historical figures, recreation of certain historical periods or resurrection of traditional ideas and concepts. It’s a part of the reality of social existence. I’m not judgmental towards it, but we have to think about the outcomes. This belief sometimes creates a rigid conservatism in the society. Standing against the swift changes and searching for shelter are common reactions. However, when this transforms into conservatism, the zealotry may become an element which prevents the society from adapting to the reality. History becomes an escape, a shelter.

Aren’t there meaningful reasons to escape certain aspects of the existing reality?

Recommended

Of course there are. As I’ve said, I’m not being judgmental, but interested in the outcomes. It sometimes makes people adapt to the contemporary world, as history has a soothing attribute. It consoles people with “the glorious past.” They become happy by reminiscing on “the golden days.”

What if they don’t want to accept the reality which is imposing itself on them and go for another reality?

If the interest in history breeds a dynamism that is required for the creation of another reality, which is a very rare case, it allows the society to assume a new position against the change and grants a power to direct the changes, along with rendering threats ineffective. As I’ve said it’s a very rare case; history usually is a sedative or even an opiate, in this sense.

Doesn’t the society need to be soothed from time to time?

If there is a case of anxiety, you should use sedatives, as you will need it. However, according to my observations, the nostalgic interest in history makes it hard to accept the reality and to take necessary measures against threats in today’s Turkey. The necessity of historical education for creating a correct identity has always been discussed. For instance, in the past, the name of the history course was “national history.” It was national in both senses: it told the history of the nation and it employed a national perspective. When recounting the events of the war between Ottomans and Serbians or the struggle between Tamerlane and Bayezid I, it’s biased in favor of the Ottomans.

Considering history is continuous and is a part of the society and its perception, isn’t it natural to have such narration?

It’s definitely normal; however, it requires looking at history from a singular point of view. The national is believed to be a means to reestablish our society; yet, with time, different data emerges, revealing that it’s not as it’s told. “Truth hates delay,” as the saying goes.

History has multiple dimensions; each perspective provides a different reality. An identity set on a singular perspective starts to become fictitious, leading the people to question the once unquestionable aspects.

Let me tell you the story of my friend. His father was a Turkish nationalist and he claimed that he was a purebred Turk. One day he was ill and went to the doctor. According to the result of a medical examination, it was found that he had Thalassemia. A purebred Turk couldn’t have Thalassemia, as it is a Semitic illness; so, at least one of his ancestors had to be of Semitic origins. Learning this, my friend’s father was devastated. Everything he believed in was destroyed by a simple reality. It’s absolutely devastating to learn that the reality you created in half a century is wrong… The same is correct for the society. If you absolutize a singular historical narration and interpretation, while basing the social identity on it, the society will start to question their collective identity as a result of emerging data.

The objective perception of history emerged with modern academism and they’re still trying to make it more common. However, since the beginning, the past was always perceived from a certain perspective, which was probably true for all societies, and, in this sense, it’s inevitable that social identity is based on this. Isn’t that so?

Here, we have to talk about the multiple historical narrations. Before the emergence of the nation-state, the history was told from various perspectives. However, with the emergence of the nation-state, one of these interpretations was absolutized as the only truth.

After that, the perception and knowledge of the past are fragmented; thus, the existence of different narrations is natural. On the other hand, nation-states absolutize a certain narration to create a common identity for the society. If you open a schoolbook on history or look at the general direction of historical research, you will see a bunch of research which was conducted to address the deficiencies of the created identity. This research creates perspectives that are theoretically contradictory and incompatible.

For example, looking at the relatively short history of the Republic of Turkey, we can see that three contradictory perspectives on the Ottomans are told in three different eras as the only reality. After a time, this transforms history into an ideological utility. Its subjectivity is being utilized. In this sense, I believe history works in a similar way with the human mind; both find and process past events and base what is transpiring today on it. The human mind constantly restructures the memories in accordance with today’s conditions; meaning that if we love somebody, we will remember the best memories with them. The same is true for the opposite situation as well. Thus, we interpret the past according to our notions. Our minds erase certain memories that could make us unhappy and revive those memories when we are expected to be happy.

So, you mean we’re always fictionalizing the reality.

Definitely, like in Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s novel, Red Monday. All characters know the event beforehand, yet they explain the outcomes differently. The mind fictionalizes the past according to the events of today and we’re actually fictionalizing many aspects of the memories that we are very certain of. Our minds trick us in many ways.

Adalet Ağaoğlu has a beautiful essay at the beginning of her book, Göç Temizliği. For a periodical, Ağaoğlu reviews her recollections of the past and tries to write down the details. Then, she shows what she has written down to her siblings. After reading it, they object to certain details: “That event didn’t happen that way. Also, the house had three rooms, not two”, “You say that there was a tree in the front of our house, but that tree was elsewhere.” In her essay, Ağaoğlu tries to retrospectively analyze why she believed that the tree was in front of the house and why she interpreted certain events the way she did. It’s a lovely essay on how our minds work. We actually do the same; we always relocate, merge or divide certain aspects of the past. We remember it in a certain way. Therefore, I believe that it’s reasonable to utilize history in this way; however, a constantly shifting history and its utilization may cause issues with people’s identities, rendering them insecure. In this sense, I think the role that history should play was inverted.

Then, you believe that history should supply us with accurate information about the events and concepts of the past?

We have to consider that all information comes with doubt, as history doesn’t possess certain and absolute facts. These facts can be only extracted from putting events into a sequence, synthesizing different historical narrations, thus creating causality. It’s next to impossible to do this. People are mostly attracted to the intricacies of the events.

Today, historians are appearing on the television and providing information about the field that they are specialized in. These shows are pretty popular. How do you evaluate them?

I regard them as tabloid programs. As you know, they’re also very popular; a celebrity dining with someone, rumors, expenses of celebrities and such. The history programs on the television have the same format. They’re extracting the lives and manners of historical “celebrities.” They’re also mystifying the events and the historical figures; there’s mystification, rather than objectification. These programs are offering to reveal the mysteries and to tell a never known fact about their subject matter. This offer intrigues the people.

It’s believed that the society will consume it. In those programs, history merges with stories, literature and legends, creating a product for popular consumption.

People are interested in the unknown. They are probably trying to understand the unexplained dimensions of their lives through these programs.

Isn’t it only a facet of the issue? Perhaps the other facet of this is to reconnect with historical events which shape their identity by relearning them. For instance, subject matters like Selim I, Mehmed II, the conquest of Istanbul and Abdulhamid II shape people’s identities, or people define themselves in reference to these historical figures or events. Can we talk about agency of the people here?

Sure, we can. Once I had been to Andalucía. When I was little, I had read a novel on the fall on Andalucía, which fascinated me. While I was there, I realized that I was actually living the novel.

How?

I mean, I was in Andalucía, for sure; visiting Alhambra, the Mezquita of Cordoba and the Alcazar in Sevilla… Yet, I was experiencing the feelings that the novel had shaped. I was always looking for it. Even when I was really there, the image of the novel shaped me. Was I discomforted by this fact? Maybe not much, but I remember telling myself “I believe I should travel here once again to see the real Andalucía.”

Why?

I have to erase the image that the novel has imprinted on me. I realized this by the end of my trip there, that I wasn’t interested in the reality of the place. Andalucía was there, along with a community, their lifestyle and such; yet, I was pursuing a five centuries old image of the region, rather romantically. That image was only fiction. Most of the people are interested in history in a similar way; they seek a fiction within history and that fiction is shaped by contemporary notions and needs. For this reason, I’m always reserved towards so-called accurate historical facts, as we learn in time that they aren’t that accurate.

How do history, politicians, social memory and expectancies intersect?

We see that when politicians discover this inclination and interest, they use it masterfully. Sometimes they identify themselves with a historical figure, or use a historical figure as a take-off point. If the society is in a bad shape, myths of heroism are spread; there is an immense effort to identify certain politicians with figures of these legends in order to manage the social imagination. In 2001, right after 9/11, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad made a speech in front of the Saladin monument [in Aleppo], while constantly referring to Saladin. As a uniting figure, Saladin was used by al-Assad, as he believed the invasion of Iraq would affect Syria. Similarly, Saladin’s image is also used in Turkey; however, it’s a contradictory image in Turkey which actually threatens al-Assad’s rule in Syria. There only was one Saladin, but he has multiple images and perceptions.

If history is fictional, uncertain, dynamic, and could be repurposed according to the needs of the day, it will never cease to exist and it will be perpetuated, as the politicians are a part of the social reality. In this sense, maybe we can consider it as the swift and effective reemergence of radical interpretations and a reconnection to the early Republic era.

Today, I believe any perspective on history could become dominant and none would surprise me. Once it becomes a malleable object, history is a fiction that can be authored by the ones that have adequate power.

Or, maybe we have to continue facing our past.

We don’t face the past; we only discuss our positions today. That’s why the discussions are so heated. Sometimes politics functions through allegoric discussions. Even though we are actually discussing the events of the day, we always refer to the past events, as we can’t discuss today’s event that clearly. I believe that the future, rather than the past, has to be discussed in an ordered and well-functioning society.

As far as we know, today the politicians in China, Russia, Europe or the US don’t refer to history that much? What would you say about this?

They only employ symbols from time to time and that’s it. For instance, Russian President Vladimir Putin participated in a mass service in a church where previous Russian tsars participated in masses. This symbolization was enough. Returning to one of your previous questions, I believe it’s closely tied with the identity crisis. Societies which aren’t certain about their identities and which feel as if they are under threat look more into the past.

Would you like to add anything?

Apparently, people’s interest in history will continue to exist. This interest has to be transformed into something useful. If we can discuss today’s issues without sticking in the past, we’ll achieve this aim. Disregarding the issue at hand and placing in the past will only make these issues more complicated.

Prof. Sunar, thank you very much again for sharing your valuable time with us for this exclusive interview.