Disregarded by many developed countries and neglected by the Muslim world, the humanitarian crisis in Myanmar found a voice through Turkey, once again highlighting the country’s prominence in humanitarian aid. After President Erdoğan’s meeting with the Myanmar administration, Turkey will extend its helping hand to the region and its people through the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (TİKA).

Providing humanitarian aid has been a strong cultural trait of Turkey. During the time that the government has been standing firmly against the massacre in Myanmar, it must not be forgotten how Turkey was the only country that took an initiative of help during the famine in Somalia in 2011. While no politicians visited Somalia, President Erdoğan visited the country with his family, ministers, and representatives of business and sport in order to draw the international arena’s attention to the crisis that was occurring in Somalia.

In addition to Somalia, disregarding the political and economic repercussions, Turkey did not remain idle to the Israeli violence in Palestine. During the 2009 World Economic Forum’s “Gaza: Peace in the Middle East” panel, Erdogan’s firm stance against Shimon Peres clearly illustrated his government’s position on the Arab-Israeli conflict. Then prime minister, Erdogan’s “one minute” slogan became characterized of Turkey-Israel relations. Diplomatic relations further deteriorated after the 2010 Gaza flotilla raid, which was organized by the Foundation for Human Rights and Freedoms and Humanitarian Aid (IHH). Israeli commanders that landed on the deck not only prevented the aid from being delivered to Gaza but also killed 10 activists who were on board.

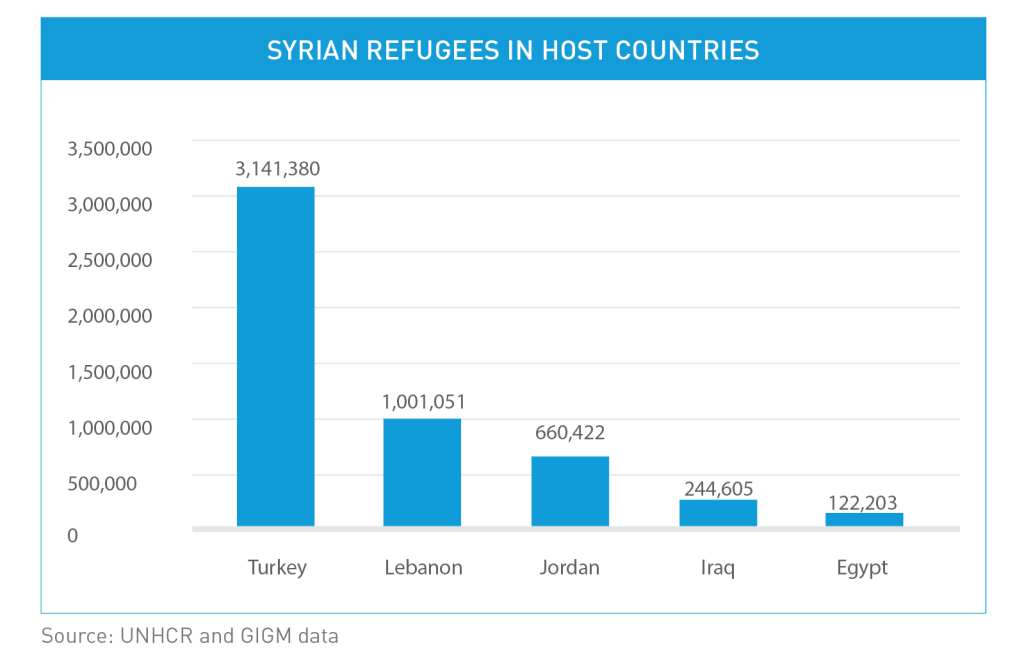

Another conflict in the region, which Turkey has approached with a humanitarian perspective is the Syrian civil war. Pursuing an open-door policy, Turkey has welcomed Syrians fleeing chaos and conflict. Followed by Jordan and Lebanon, Turkey is the largest host of Syrian refugees. According to data provided by the Republic of Turkey Ministry of Interior Directorate General of Migration Management (GİGM), there are 3.141.380 registered Syrian refugees in Turkey. While hosting such a capacity contains political, economic and social burdens on the state, Turkey has maintained high standards in regards to its refugee camps and social inclusion of refugees into areas such as education and employment.

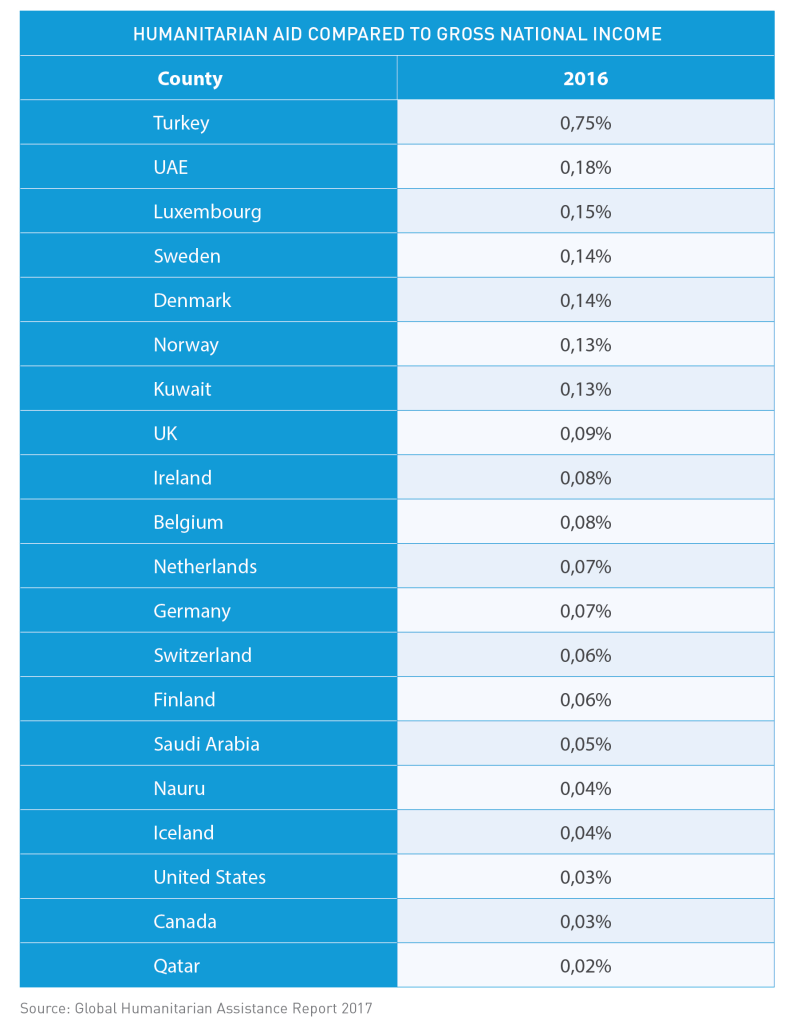

It is definite that a country’s economic condition is not an indicator for humanitarian aid. While 18% of the host countries are low-income economies, only 7% consists of high-income economies. Therefore, superior economic conditions do not ensure a better performance in humanitarian aid. This is further reflected in the graph provided below.

Thus, it can be argued that the Turkey is successful in lending a helping hand and aiding those in need. While the success of this activity could be measured through quantitation, sincerity of aid ultimately relies on not expecting any political or economic return.

‘Developing countries’ designed for chaos

In order to assess Turkey’s performance in terms of humanitarian aid and provision, one must glance at the 2017 report of Global Humanitarian Assistance. This report, alongside the concept which has become “Humanitarian Day” both carry relevance for the topic in discussion. It is important to briefly note here the significance of the day the report was published.

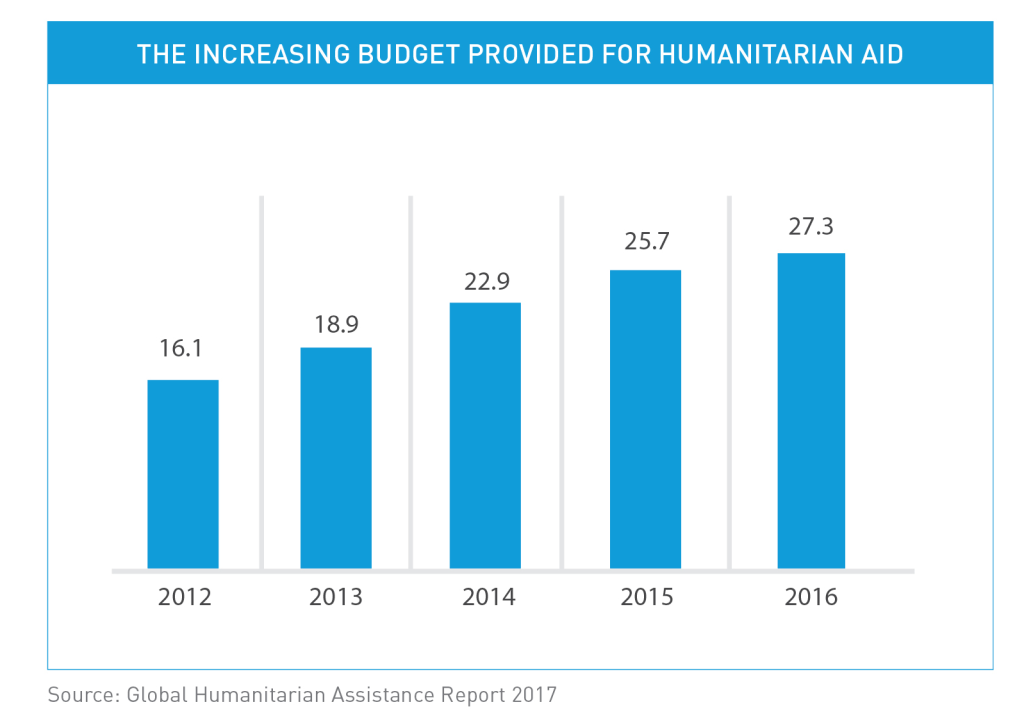

Commemorating the day UN headquarters in Baghdad was victim to a terrorist attack, August 19 has become acknowledged as World Humanitarian Day since 2008. The World Humanitarian Day provides a minimal opportunity for issues of development and crises to rise on the political agenda and for international organizations such as the UN to measure their success in areas such as the ability to provide clean shelter, water, food and security to those in need. Trends in the amount of humanitarian aid between 2012-2016 indicate that the need for humanitarian aid is increasing by the day. While $16.1 billion was dedicated to humanitarian aid by the state, EU and private sector in 2012, this amount has increased to $27.3 billion in 2016.

Recommended

The strive for power in the international arena and the self-interest of societies ultimately harms socio-economically vulnerable people. In this respect therefore, the regions of crisis and the populations affected by war and famine have certain similarities between them. It cannot be denied that the wars in the Middle East and Africa today, are to a certain extent, a legacy of colonialism. Ethnic and sectarian conflicts that have been driven to the fore in the regions in question are potentially due to the fact that the borders of countries were drawn by the colonial powers. The case that emphasizes this best is the Rwandan genocide, where the Tutsi were slaughtered by members of the Hutu majority.

The power relations that were formed during the colonial era remain stable today. When we talk of humanitarian crisis, deprivation and impoverishment, we are addressing a specific ‘area’ of the world: the less developed countries. While it may be common to read of children dying from famine in Sudan or Somalia, reading of the same story occurring in a western country will come as a shock. Further, while child soldiers in Syria are perceived as commonplace, participation to Daesh from the west is perceived abnormal.

The International assessment of aid

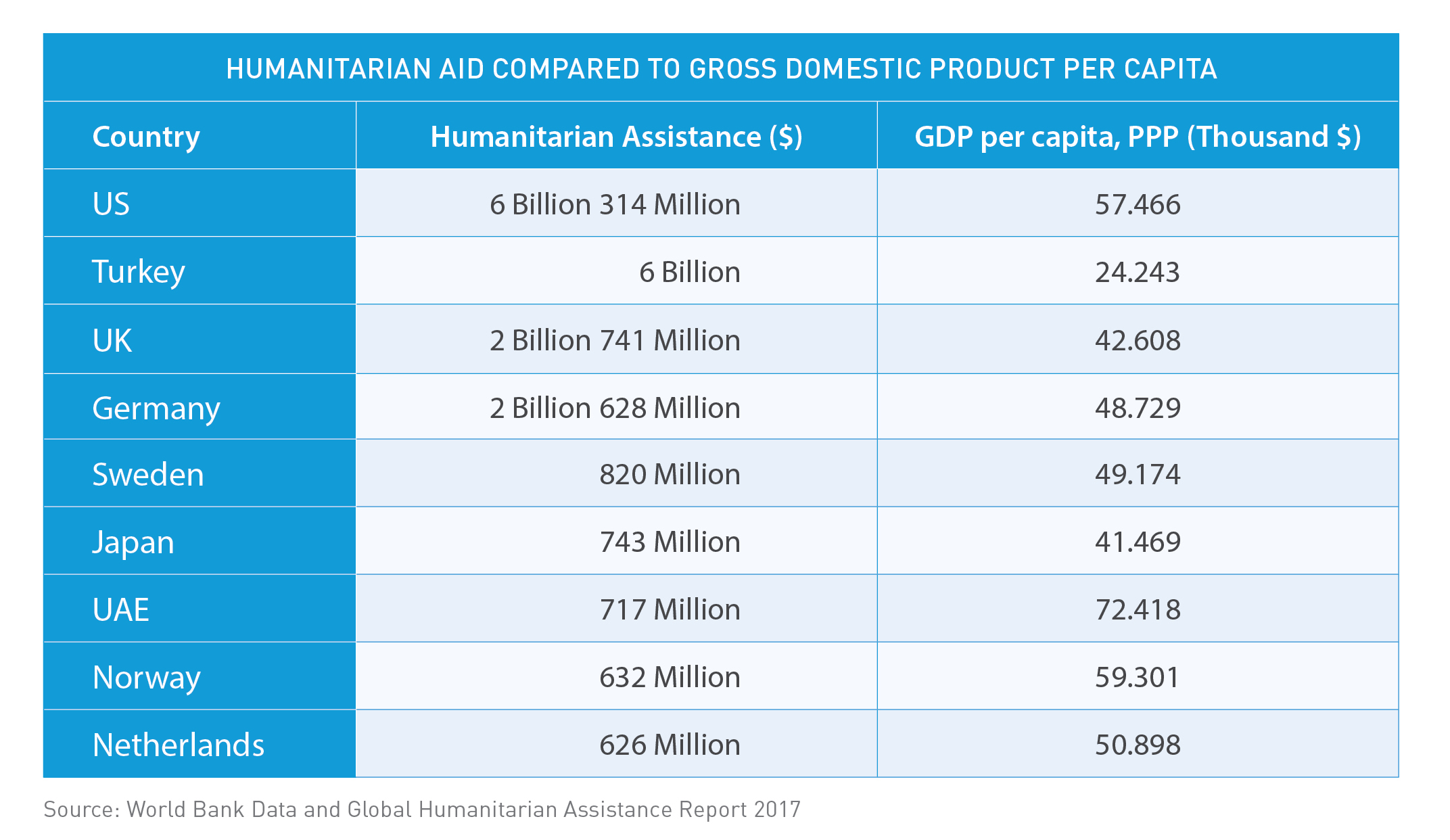

Providing $6 billion in 2016, Turkey is the second country that provides the most humanitarian aid. Looking at the top ten (see list below), we see that the US ranks first, while Turkey second. They are followed by the UK, Germany, Sweden, Japan, UAE, Norway and the Netherlands. When one considers the income per capita according to purchasing power of these countries in 2016, there is a negative correlation between income per capita and humanitarian aid. Ironically, the richer the country, the less humanitarian aid they provide.

Moreover, Turkey dedicates 0.75% of its Gross National Income to humanitarian aid. Among the top ten, the US dedicates 0.03%, the UK 0.09%, Germany 0.07% and Sweden dedicates 0.14% of their GNI to humanitarian aid. Turkey’s emphasis on humanitarian aid in comparison with developed countries like UAE, Luxemburg, Sweden, Denmark and Norway also reflects on quantitative indicators.

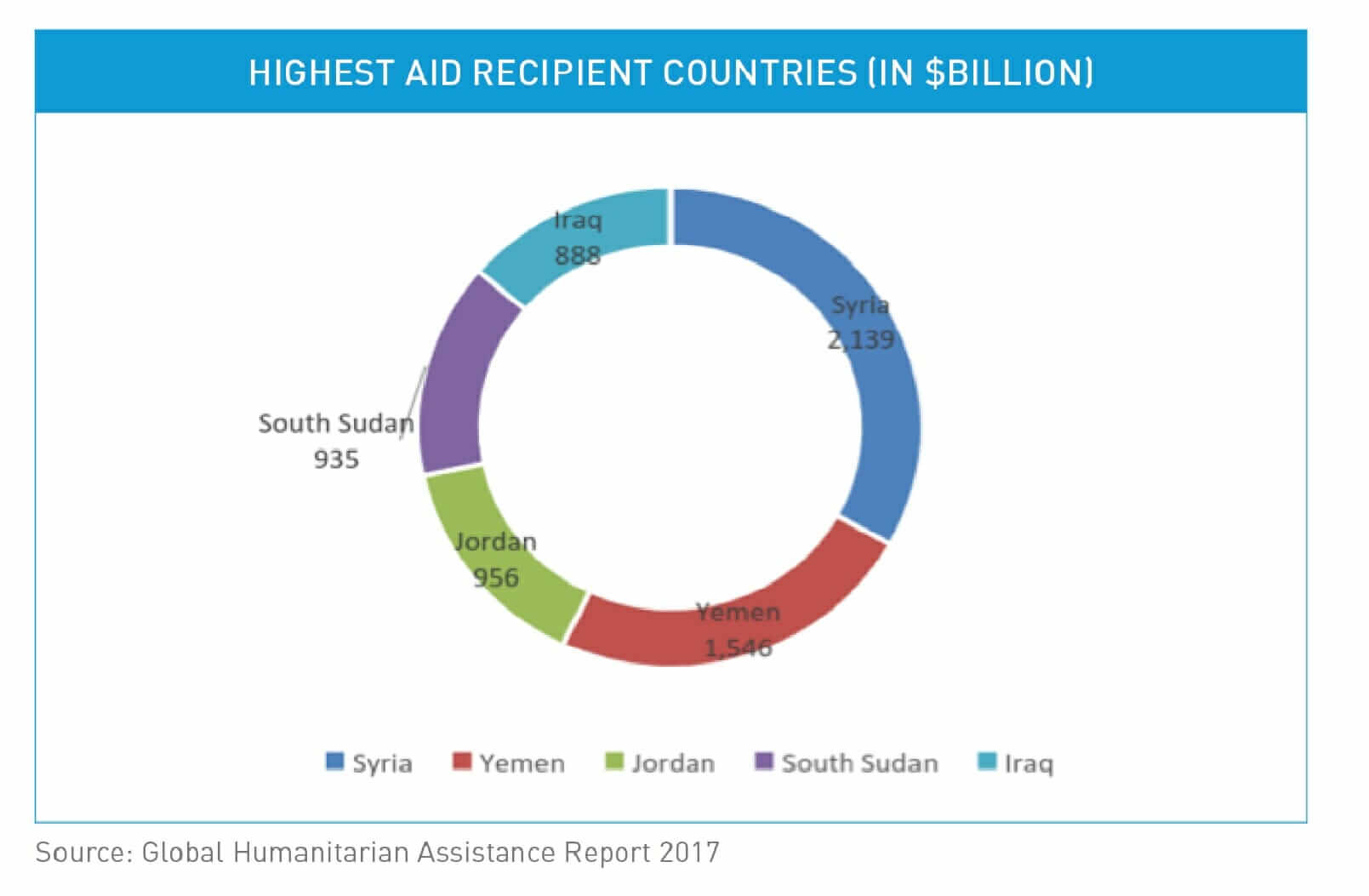

Ranking of the countries receiving aid indicates that political and social stability along with economic development are determinants of need for humanitarian aid. Met with idleness by developed countries, the chaos and conflict in Syria puts the country on the top of the list. Syria is followed by Yemen, Jordan, South Sudan and Iraq. Receiving $2.129 billion humanitarian aid, Syria is followed by Yemen with $1.546 billion, Jordan with $959 million, South Sudan with $935 million and Iraq with $888 million. Analyzing these countries, beside economic development, we can see how important political stability is for social and economic prosperity.

The increase in the number of people in need of humanitarian aid highlights that political and social crises and chaos are deteriorating in less developed or developing regions. Interpreting the increase in resources dedicated to humanitarian aid as an improvement in awareness and sensitivity would only be unrealistically optimistic, especially seeing the list of countries that provide humanitarian aid. However, this could only be resolved if countries that disregard humanitarian catastrophes cleanse themselves from political and economic ambitions. It should be remembered that humanitarian crises are not necessarily regional threats, but pose a threat to the whole world.