Facing a labor shortage after World War II, in October 1961, Germany created a program to bring in so-called gastarbeiter or guest workers from Turkey. Besides Germany, other Western countries such as the Netherlands, Belgium, France, and Austria also needed workers to boost production in their booming postwar economy.

Many of the Turkish guest workers who arrived in the country never left, and created a minority community that forever changed the demographics of Western European countries. As stated by the German Federal Foreign Office, “We called for workers, but people came.”

Today, sixty years on, individuals with Turkish roots form one of the largest minority groups in EU countries. Politics Today interviewed six motivated, educated young adults from five different countries who all share a migrant background.

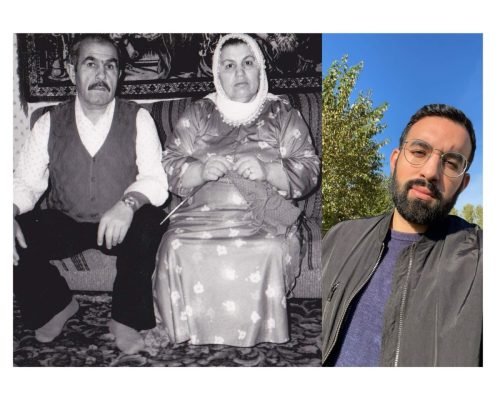

Burhan Bayhan, 31, Denmark

Burhan Bayhan, a 31-year-old Danish-Turkish historian living in Copenhagen, told Politics Today he was never able to meet his grandfather as he died when Burhan was still a baby. This made him try to meet his grandfather through understanding and studying his legacy.

My grandfather Kemal Bayhan was one of many guest workers who sought their luck in Denmark in the late 1960s. He was born in a village in Sivas, Turkey, where he worked as a farmer. He got an invitation letter from an employer through a friend from his village who was already working there. He left behind a wife and five children, and came to Denmark in November 1969. He worked for many years in low-paying industrial jobs to build a better future for his family which he brought to Denmark in 1980 through family reunification.

As a kid I used to play with his coin collection and ask my parents questions about him. But many questions about his first years in Denmark remained unanswered. So last year, I went to the Danish National Archives in hope of learning more about him. I found his immigration case, which answered all my questions. To my big surprise, I also found a picture of him and my grandmother which I had never seen before – this was really an emotional moment for me.

In a time where hatred and anti-immigrant rhetoric against immigrants became the norm, we should remember that these hardworking guest workers sacrificed a lot including their health for building and straightening our welfare system from which we benefit today. I feel really proud and lucky to be a descendant of a Turkish guest worker. Thanks to him, today, I am a well-educated and open-minded person, and their struggles keep inspiring me and giving me strength.

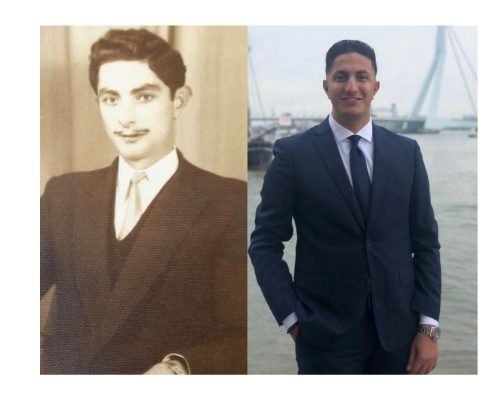

Rıdvan Denizoğlu, 21, Belgium

The process of adjusting to Belgian culture made the 21-year-old Rıdvan Denizoğlu question his background. This led to an identity crisis in which Denizoğlu has been asking himself whether he is Turkish or Belgian. After a long period, he came to the conclusion that it is a huge benefit to be in-between both cultures.

My grandparents were among the first Turkish guest workers to arrive in Limburg, Belgium, in the 1960s. My grandfather worked here for years in the Beringen coal mines. My mother was the first child of six, making the future generations of my family in Belgium a fact. I love to listen to my grandparents’ stories about this time, and they love to tell them. The common theme in all their stories is how hard it was to adapt when you come from a rural village in Ardahan in northeastern Turkey, and suddenly find yourself in industrial and ‘modern’ Belgium/Europe where nothing is the same.

Because of my background and experiences, I am following a primary school teacher training course because I do not agree with the way children with a migration background are treated. That is why, as a teacher with Turkish roots, I hope to realize a renaissance in which future Turkish children are treated fairly and can make the best of themselves. I am also president of the Youth of Willebroek (YoW) association. Our goal is to bring out the best in young people from all cultural backgrounds.

While dealing with such matters, I try to motivate the next generations to speak up, to use their talents, to show that we, as a younger generation, must continue the “legacy” of our grandparents. They came to an unknown place during difficult times to provide a better life for us. Despite the fact that we still have a hard time as “immigrants,” we have to thank them by working hard and to show them that their efforts were not in vain.

Büşra Suratlı, 27, Germany

Büşra is 27 years old, and was born and raised in Germany where she works as a civil servant. In addition to her work, she is studying to get her degree in business administration. Büşra talked to Politics Today about how her grandfather was homesick his entire life.

My grandfather Mustafa Özcan who was originally from Trabzon, left his family behind and came to Duisburg, Germany, as a “Gastarbeiter” in 1970 where he stayed with many other Turkish guest workers in a dormitory. They stayed in one room where everyone had his own closet and shared the same bathroom. My grandfather could only communicate with his family in Turkey through letters. Sometimes he would record an audio on cassettes and send them by mail which would take 10 days.

After 1976, my grandmother and children also came. In Hüttenheim, a total of six people lived in a two-and-a-half-room apartment. My dear grandfather used to travel 20 km a day by bike to go to the train station in the city center and buy the Tercüman newspaper which wasn’t even up to date. Most of the times it was from two days ago, but it was a great blessing for him.

Although his children lived in Germany, in the late ’90s, my grandfather decided to go back to Turkey. Then, he was only able to see his children and grandchildren during holidays when they would visit Turkey. The Turkish word “gurbet,” which means the state or feeling of being a stranger in a foreign country, or longing for one’s homeland, always remained part of my grandfather until his death. Being alone in Turkey made him become homesick for his family.

As a bilingual European Turk, I am currently working as a civil servant in Germany. I proudly tell the story of my grandfather to everyone. I feel very lucky for the decision he made. Most of the time, I think about his suffering and visualize it in my mind. My wish is to pass on these memories to the next generations, and not to let them forget that we are here because of them. I think it is important to represent our culture and homeland in an exemplary way for the sake of all the sufferings they went through.

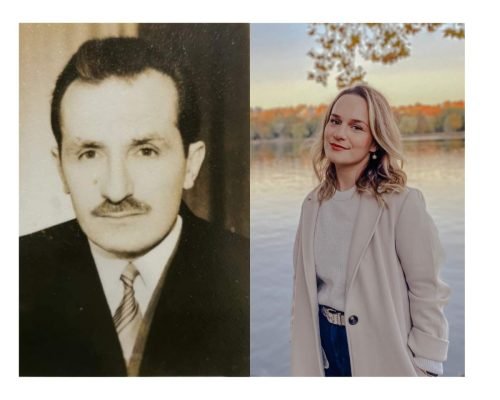

Ahmet Turan Atmaca, 26, Netherlands

Ahmet Turan is 26 years old and is working in the field of environmental sustainability through recycling. He was born and raised in Rotterdam in the Netherlands where he was able to study at the same building his grandfather once worked at as a guest worker.

In the beginning of the 1960s, my grandfather Ahmet Atmaca came to the Netherlands where he stayed and worked at the Rotterdamsche Droogdok Maatschappij, which pre-World War II was the largest shipbuilding, ship-repair, and machine building facility in the port city of Rotterdam – it existed between 1902 and 1996. I’m proud to say that my grandfather was part of such an important company when it comes to the Dutch shipping industry.

I’m even more proud of the fact that I was able to study later at the same place my grandfather once worked. The older I get the more I realize what kind of hardship my grandfather had to endure. From a small village in Trabzon, a city on the Black Sea coast of northeastern Turkey, to the port city of Rotterdam situated on the Maas River. Only for this reason these two cities will forever hold a special place in my heart.

In 1994, my grandfather decided to move back to Istanbul. He would come and visit us in the Netherlands from time to time. Every time he came, we would take different walking routes in Rotterdam where we had the most precious conversations. I remember he loved to look at the Maas River, maybe because it felt like home, the Black Sea. I really think that my passion for caring for nature, the environment, and my admiration for the sea comes from the relationship I had with my grandfather.

Unfortunately, my grandfather passed away earlier this year. As the grandchild of a migrant, I think it is important to continue talking about their sufferings otherwise the next generations won’t be aware of what our grandparents once did for us. They really sacrificed their lives for us. Most of the Turks in Europe owe this to their parents and grandparents.

Yasin Güler, 25, France

Yasin is a motivated councilor of the municipality of Erstein, a city near Strasbourg, where he was born and raised. Yasin, who is 25 years old, holds a master’s degree in international law and currently lives in Paris. Here he works as a compliance Manager for an MGA Insurance Managing General Agent. He also has a great passion for Turkish classical music.

My story starts the same as a lot of other Europeans with Turkish roots. My father saved some money in the early ’80s to move to France. As a result of the introduction of the law on family reunification, my mom too, was able to come to France. Being the youngest child of a family of 5, I have always been very interested in culture, sports, and music. At this stage of my life, I realize that I, just like other children of migrant parents, have been asking myself questions the answers of which weren’t actually that hard to find.

I realized that even though my roots are miles away, through my passion for art and music, I slowly start to understand that I belong to both countries. From a very young age, I’ve been aware of the possibilities the country I was born gave me, and, therefore, it was more than crucial to give back to the French community through my education and personal achievements. An example of this is my work for the municipality after I became a councilor. As the second- and third-generation Turks in Europe, our lifestyle and achievements today we owe to our family members, friends, and every individual who helped us through this process.

Sometimes I’m exposed to the question of whether I feel more Turkish or French. I use the term “exposed” because I don’t think that there is a certain answer to this: there are just people with stories and paths they have walked on – that is what matters.

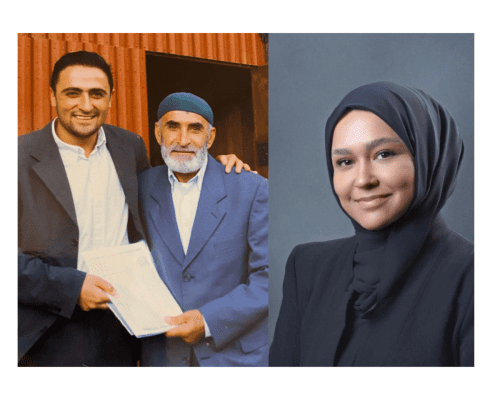

Latife Özdemir, 23, Netherlands

My grandfather Vahdettin Özdemir was born and raised in a small village in Elazığ, southeastern Turkey. After elementary school, he had to stop his education and work with his father because of their poor conditions. He once told that they only had one pair of shoes at home and that he had to share this with all his siblings. In the winter, he sometimes had to walk barefoot through the snow.

In the early ’60s, my grandfather went to Germany, where he worked in the coal mines for a long time. After a few years, he decided to move to the Netherlands where he stayed in a dormitory with a lot of other guest workers while working at the harbor of Scheveningen in The Hague.

My grandfather used to send voice messages through cassettes from The Hague to his village in Elazığ to my grandmother and their children. My father tells us that whenever a cassette would come, the whole village would come together to listen to his stories and how hard life was abroad. Sometimes the cassettes came months later. My grandfather used to sing Kurdish songs known as “Dengbêj” (a genre of singing storytelling) in which he expressed his feelings and the hardships he was going through.

Because my grandfather had to stop his education from a very young age, he encouraged my father to study. Although my father was lucky enough to be able to continue his education in the Netherlands, it wasn’t always easy to adapt to the culture and learn the Dutch language. In 2001, three years after I was born, my father got his master’s degree in criminal law from Leiden University. Currently, I am studying law as well, and I am more than proud to hear these stories and reflect on the migration and integration history of our family. I hope the next generation of Turkish Europeans will continue telling these stories and become more active as an integral part of modern European culture.

Recommended