Since the nationalist Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) administration in the early 20th century, the modernist elite in Turkey have tried to create a homogenous and “harmonious” Turkish national identity. The process of building a national identity in Turkey has been controversial and, at times, cruel. Mass deportations of Ottoman Armenian and Rumelian Muslim populations, and also the exchange of the Muslim population in Greece with the Greek population in Anatolia, created a religiously homogenous society. Although ethnic, linguistic and sectarian diversity had been preserved to a certain extent during the early Republican era, there were moments when this diversity was considered a potential threat to national security and unity.

Recommended

Unfortunately, the crisis in Syria has stimulated the identity-related fault lines in Turkey, increasing the risk of social contention.

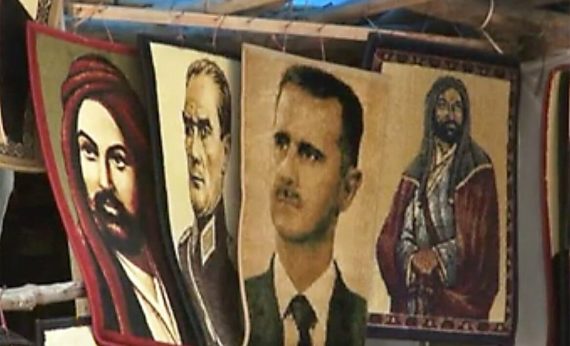

Efforts to create a homogenous society during the early Republican era failed several times due to the resurgence of ideological and ethnic identities. Nonetheless, the top-down Turkish national-identity-building project of Mustafa Kemal is still regarded as a “successful” policy due to its immense defects. Ongoing developments in the region have drawn attention, once again, though unenthusiastically, to the harmonizing aspect of national identity. Ethnic and sectarian fragmentations in the Middle East, primarily ethnic terrorism and Salafist Jihadism, have become a serious threat to Turkey’s national security. The ongoing war in Syria has complicated the identity puzzle in Turkey, leading to the dangerous potential of triggering identity-related radicalizations.

The risk of ideological and political polarization in Turkey constitutes a serious challenge. In addition, the civil wars and uncertainties in Syria and Iraq could become a source of tension and polarization within Turkish society. The increasing material costs of the civil wars in Turkey’s neighboring countries, the presence of more than 3 million Syrian refugees living in Turkish territories and the mounting security risks are further fueling the concerns of the Turkish people. The Turkish government feels that the country’s Western allies are not taking these security worries seriously; in addition, the Western allies have proved unwilling to shoulder Turkey’s economic burden. Once ardent supporters of EU integration, the Turkish people are disappointed and feel abandoned by the country’s Western allies as Turkey faces the uncertainties of the spillover effects of the Syrian crisis.

Once ardent supporters of EU integration, the Turkish people are disappointed and feel abandoned by the country’s Western allies.

Most people in Turkey are fully aware of how the peace process ended, as the PKK attacked the Turkish Security Forces in the summer of 2015. This was partly related to the developments taking place in northern Syria, namely, the increasing power and international legitimacy of the PYD, the PKK’s Syria branch. The PYD managed to gain legitimacy and material support by positioning itself against ISIS within the Syrian context. So far, the Islamist, Alevi and Turkish nationalist dimensions of the identity polarization in Turkey have been either avoided or underestimated, owing to the absence of direct confrontations and violence. The terrorist attacks, bombings and the never-ending funeral ceremonies of the martyred Turkish soldiers are causing Turkish citizens further unease.

Secular nationalists feel further strained due to the hegemonic status of the conservative democratic AK Party in Turkish politics, which has gained ground over the last fifteen years. The rise of Salafist Jihadi radicalism in Turkey’s backyard is causing apprehension in all sectors of society in Turkey, including the conservative religious groups. For decades, conservative religious groups in Turkey managed to refrain from illegal activities and violence and pursued their goals through democratic channels, adding legitimacy to Turkish democracy. At one time, the military, judges and secular establishments had been considered the strongholds of, occasionally oppressive, secularism in Turkey; now, it seems that none have maintained their power. The loss of the relative influence of the institutions that oversee the secular foundation of the republic has caused some of the secular urban groups to feel uncomfortable.

Ethnic, sectarian and ideological tensions within the wider region have had definite spillover effects in Turkey.

Ethnic, sectarian and ideological tensions within the wider region have had definite spillover effects in Turkey. Turkey’s border with Syria is 911 kms long and all demographic groups, including Kurd, Arab, Turcoman and Assyrian, exist on both sides of the Turkey-Syria border. Indeed, the border between Turkey and Syria was drawn arbitrarily as a result of colonial bargaining in the early 20th century. Not surprisingly, given these close links between the two countries, ethnic, sectarian and political tensions on the Syrian side of the border have certainly affected and will continue to affect Turkey.

Different social groups in Turkey hold the expectation that the Turkish government will support groups in Syria to enable them to feel more connected. In 2014, a group of Kurds had expected the Turkish state to support the PYD against DAESH in the battle for Kobani. The Turkish government’s unwillingness to engage militarily was manipulated by the political wing of the PKK, which led to outrage among the Kurdish ethno-nationalists. Conservatives and Islamists wanted the AK Party government to support the moderate opposition in the Syrian civil war, whereas the secular left and the Alevis wanted the government to restore its relations with the Asad regime. Some influential names among the secular elite also wanted Turkey to stay away from the “Middle East Quagmire” and to turn instead to its traditional Western allies. Clearly, it is almost impossible for the AK Party government to meet the expectations of all social groups at the same time.

Different social groups in Turkey hold the expectation that the Turkish government will support groups in Syria to enable them to feel more connected.

Among the different social groups, there is increased excitement among the Kurdish ethno-nationalists. This group perceives the increased autonomy of the PYD in Northern Syria, under the conditions of the civil war, as a positive development, even an historic opportunity for independence or a strong autonomy. Many young PKK terrorists from Turkey either volunteered or were forced by the PKK to join the Syrian civil war in the ranks of the YPG. Some Alevis, on the other hand, fear that the anti-regime stance of the AK Party government in the Syrian civil war has sectarian underpinnings.

During the Arab Uprising, the Turkish government was in favor of political change in Syria and elsewhere, when Turkey chose to support the opposition politically and diplomatically. This support was interpreted differently and ideologically among some Alevis. The Alevis were concerned about the weakening of the secular foundations of the Turkish State, which previously had been neutral and distanced in its approach to the regimes in the Middle East. As a result, certain Alevis believe that the AK Party administration is pursuing sectarian goals within the Middle East.

Turkey’s increased security cooperation with Qatar and Saudi Arabia have further elevated such worries. From among the extreme-left Alewites (Arab Alewites differs from majority Alevis) of Hatay, few joined the Syrian civil war in the ranks of the Asad Regime as foreign fighters. Some people from Turkey joined the Syrian civil war in the ranks of groups such as the Free Syria Army, Ahrar al-Sham, Jabhat al-Nusra and even DAESH. Those who are fighting on opposing sides of the Syrian civil war may bring hostilities and their fighting experience back to Turkey, which poses a serious risk to Turkey’s national security.

In addition, some young nationalists crossed the border to join the fight to defend Turcoman villages against the regime’s forces. For the time being, the AK Party government’s humanitarian aid to Turcomans, as well as active policies and diplomatic efforts to support Turcomans on the Syrian side of the border, has curbed Turkish nationalist sensitivities; however, fluctuations are always possible. For instance, there is increased nationalist sensitivity concerning the PKK-PYD attacks on Turkey and the demographic engineering against the Turcomans and Arabs on the southern side of the border.

People in Turkey who are anxious about the economic and security-related spillover effects of the Syrian crisis may experience some friction with the Syrian refugees.

Another important identity-related issue is raised by the situation of more than 3 million refugees from Syria and some from Iraq. At the beginning of the crisis, most people believed that the Syrians would return to their homes when the civil war came to an end. However, more than five years have passed since the beginning of the uprising in Syria and, as most of the country’s cities are devastated, most of the refugees have no safe place to return to, which means that the majority of Syrian refugees will become permanent residents of Turkey.

There is increasing sensitivity about the immigrants, especially within the cities neighboring the border of Syria, such as Kilis, Antep, Urfa and Hatay. The populations in those cities are concerned about the spillover effects of the Syrian civil war. Although the refugees from Syria are also the victims of the brutal civil war in their home country, people in Turkey who are anxious about the economic and security-related spillover effects of the Syrian crisis may experience some friction with the Syrian refugees. There is always room for potential escalation. The government has regulated to accommodate Syrians on a more regular and stable basis; however, the existing identity-related status quo in Turkey can hardly be maintained with within the fast-evolving conditions.

If not skillfully managed, serious social frictions may arouse.

The mounting civil wars in both Syria and Iraq have increased radicalization at Turkey’s southern borders. Turkish citizens who live in the bordering cities feel anxious. These fears trigger skepticism and may lead to polarization among different identity groups. So far, the psychological impacts of the Syrian crisis on identity groups in Turkey remains an underestimated issue. In particular, people living in the cities bordering Syria and Iraq are experiencing this tension more intensely. If not skillfully managed, serious social frictions may arouse. Becoming aware of such a potential threat is a crucial first step, but following steps need to be taken to ensure that communities in Turkey are more resilient to such tensions.