One of the most important actors on the night of July 15, 2016, was the personnel of the Directorate of Religious Affairs. Calling mosque staff in all cities to duty, the directorate consolidated the people’s resistance against the coup taking place in Istanbul and Ankara. In this respect, in an unprecedented way, mosques broadcasted messages calling people to go out on the streets and thwart the coup attempt. This process, during which the Directorate of Religious Affairs personnel faced dangers such as going through a conflict zone or being attacked by some Turkish citizens verbally and physically, was initiated with former President of Religious Affairs Mehmet Gormez’s verbal instruction on Ulke TV when he reached the TV channel through phone around 11:40 PM:

“I ask all of my devoted brothers out there, please each and every one of you run to the minarets. First recite salawats to Prophet Muhammad (pbuh), then invite all people of Turkey to protect their rights and will.”

In addition to this verbal instruction on TV, the directorate personnel received a text written by Mehmet Gormez around 01:00 AM:

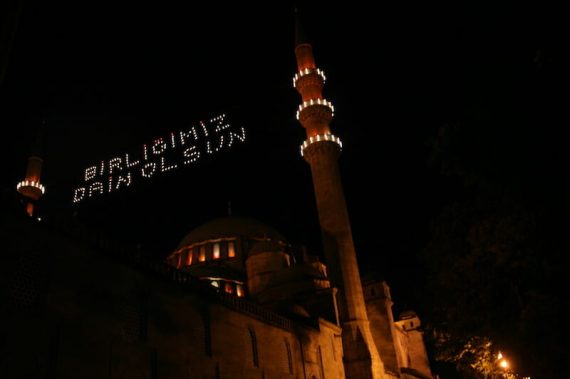

“My fellow devoted brother, doing whatever we can to protect the rights of our people is our duty. We can never allow this country and its people to be divided, deprived of peace and prosperity along with the will of people being infringed through coercion and violence. As the spiritual guides of our nation, we will stand with the people against all illegal initiatives. I call all of you to resist this heinous treachery [the coup attempt] in a nonviolent way by going up the minarets, the symbol of our freedom. Tonight, lights of minaret should remain on and the people of Turkey should be invited to protect their rights via reciting salawats.

Mehmet Gormez”

After this instruction of Mehmet Gormez, sounds of salawats, call to prayers, prayers and announcements rose from the minarets. Gormez had given the general framework to muezzins and let them do whatever they can within this framework. This situation revealed a rich potential of materials; while some muezzins recited salawats unceasingly, others were inviting people to resistance after salawats, praying in Turkish/Arabic, reciting “salat-ı ümmiye,” Turkey’s national anthem and poems.

Recommended

Shaped through improvisation in terms of content, this rich material gave insight to the relations between the July 15-religion in particular and religion-state/politics/democracy/military in general along with how these relations were perceived by Turkish society. In addition, it also revealed how the directorate personnel viewed this sinister event and how they conveyed their views to the public along with uncovering how one of the most effective motivators functioned. In this respect, this material is crucial and for this reason it would be beneficial to look at what happened on the night of July 15 from this perspective through the common points that could be found among limited sources:

Looking at the mood of these calls and prayers, it is clear that there is an apparent and dominant “war of independence” or invasion psychology. This wasn’t a coup aiming to overthrow the government, but the state, call to prayer, the flag and independence – all of which are seen as synonymous. “Europe,” “the U.S.” “Zionists,” “Christians,” “heretics,” “hypocrites” and co-conspiring traitors are behind this coup attempt. This psychology had an impact on the frequent recitation of the Turkish national anthem written along with Arif Nihat Asya’s poem “Biz Kısık Sesleriz” [“We are the husky voices”]. Meanwhile, referred historical figures also reflect this psychology: Ulubatli Hasan, Mehmed the Conquerer, Abdulhamid II, Sütçü İmam…

National unity and solidarity are among the most underscored arguments during the calls made from minarets. Undoubtedly, this was the case because it wasn’t a solely military coup; it was perpetrated by a religious order which had a social correspondence. In this respect, with the addition of indiscriminate usage of heavy weaponry against the people, the coup was seen more of a threat than just a struggle for power between two parties or an attempt to shift power. This perception was due to the damage caused by violent political and social conflicts in Syria and Egypt in the near past being still fresh in the memory of people.

Protecting democracy and the national will were two points that were frequently expressed by religious officials when calling people to resist. People were invited to take the streets not only for the love of God or country, but also for the love of democracy, while it was highlighted that the national will, elected government, president or the Parliament could be altered with arms and coups, that was a clear threat.