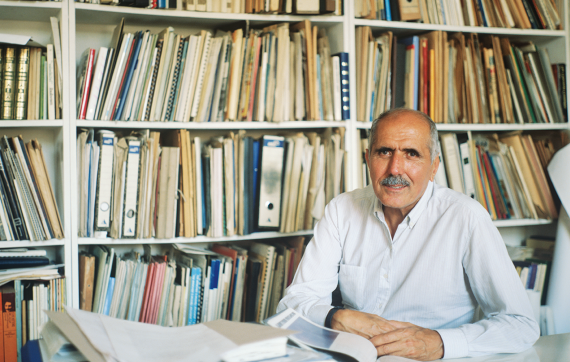

“Think of the Ottoman Empire, which developed its peculiar modernity without experiencing the Tanzimat and its aftermath; this is the type of architect Turgut Cansever is,” said Beşir Ayvazoğlu, a well-known Turkish literature and biographical writer, in his short commentary on Turgut Cansever (1921-2009). Having passed away nine years ago on Feb. 22, 2009, Cansever was a well-known Turkish architect and a prominent figure in reinterpreting and refashioning the centuries old architectural heritage of Turkey by inventing a novel approach that combines traditional architectural principles pertaining to a set of moral values and beliefs with a modern perspective. Commentators rarely miss the chance to mention that Cansever is the only architect in the world who received Aga Khan Awards for architecture three times.

Architect’s responsibility

Cansever believed that constructing an architectural work should come along with a sense of responsibility. Unlike reading a novel or listening to music, which can be interrupted privately, people have to live with architectural works for decades or perhaps for generations to come, once the construction is finished. Thus, architects must design buildings respectful to society and social values with a concern for the future. The feeling of responsibility is what turns human creatures into human beings. It is the realization of being the pearl of creation that lays the burden of thoughtfulness on various strata of existence and of the duty of beautifying the world. The higher the level of consciousness, the greater the realization of responsibility. Without such principles, Cansever warns, architects would surrender either to market conditions or to individualistic architectural fantasies.

There is an inextricable relationship between what we believe in and what we produce. Human beings are rational actors who make conscious choices, and everything they construct reflects their beliefs and convictions. Thus, ethics and ethical concerns should be closely related with architectural practice too. What kind of a relationship between architecture and ethics should be established is a vital question that needs to be answered to understand Cansever. He believed that architectural choices could easily turn into fetishs if they reflected personal pride or merely aimed for self-satisfaction. Such an egocentric attitude also increases complexity in architecture. Cansever reacts to the self-ordained deconstructivist and post-modern attitudes that came to dominate the field with ever-growing influence. Instead, moral values, such as modesty and solemnity, should lead the processes of design, material selection and construction.

Cansever had real difficulties with the creator-artist type of architect. This attitude was combined with the market realities of attracting customers, bypassing legal requirements to increase profit and personal pretentiousness that resulted in cultural pollution and spatial detachments and incoherence. A building, Cansever argues, cannot go beyond mere technological success if it does not take material, technological and biosocial levels of existence into consideration simultaneously. Cansever also criticized approaching the land and city from the perspective of bureaucrats or technocrats, or paying too much attention to bureaucratic procedures, but instead offered viewing the land and city as manifestations of divine perfection, and consequently showing due respect to it. True architectural behavior would lead to listening to the voice of nature and to understand the order of a God-created environment, as it requires encompassing all aspects of existence.

Architecture as an Islamic art form

Cansever offered a universal conception of Islamic art, which also applies to architecture, and defined it as “obeying the truth with no ifs and buts; staying away from wrongdoing; submission, modesty and conforming to the structure of existence; seeming as you are; contenting oneself with less; being conscientious toward God, all that means to build things not to impress others.” Cansever described Islamic architecture on another occasion as a “movement in calmness, having the clarity of finitude, modesty and naturalness in expression. Rather than being dramatic or compelling, it is for beauty and ornamentation.” It is also a sort of colorful and exuberant picture, full of optimism, confidence and cheerfulness.

However, his conception of Islamic architecture is not an essentialist one. According to this concept, he means architecture carries certain virtues and values. Thus, a German, Russian or Japanese city can be more Islamic than a Turkish, Iranian or Egyptian one. For example, Cansever deemed Frankfurt an Islamic city, with its population of over 20 million and whose upkeep costs are lower than Istanbul due to its city planning. Likewise, Cansever found Russian-made Istanbul-like houses as Islamic as the basalt houses of Anatolia since both take the relationship between human and nature into consideration.

Recommended

Architecture, localism and locals

Cansever expected architects to have certain qualities, such as paying attention to climate, ecology, the topography of construction, the consent of people who live in and around the place of construction, controlling climate conditions by passive methods and characterizing relations and tensions between different construction materials when used together.

Submission to the local condition of geography and using locally sourced materials were important assets for Cansever who taught that architectural work should give the impression that it is a natural part of the locality that has been built as if it has always been there. Finding locally produced architectural solutions to material problems that appear on a biosocial level of existence also means, to him, being in rapport with divine will. For instance, Cansever finds it very unreasonable and unIslamic to construct glass-covered buildings in Erzurum, an eastern city in Turkey, famous for snowy, cold winters. This means to challenge nature and challenge the given order of things, ending up polluting the world. Cansever believed that things natural and spontaneous are beautiful and closer to human nature. The most serious problem of 20th century architecture, according to Cansever, was to favor vanity and turn people into passive creatures. In contrast, he always favored local solutions to local problems with the participation of locals. He communicated with people and paid attention to their views and opinions about the work. Sometimes, criticism from non-architects could even lead him to change the facade or the public side of the design.

Cansever’s concepts

Cansever loved to use single-word concepts as illustrative tools to depict certain ethical qualities that a proper architectural work should supposedly contain, such as quietness (asudelik), objectivity (bîtaraflık), timidity (çekingenlik), piety (dindarlık), inert expression (durağan ifade), reverence (huşu), honesty (dürüstlük), simplicity (sadelik), optimism (umut), elegance (zarafet), submission (tevekkül), mellowness (yumuşaklık), respectfulness (saygı), dignity (vakar) and enjoyment (zevk). One example of how he used these concepts can be seen in his comparison between the Nuru Osmaniye and Selimiye mosques. Although some argue that Ottoman architecture was able to produce its own baroque in the 19th century, like the Nuru Osmaniye mosque, Cansever did not hold the same opinion. When comparing Nuru Osmaniye and Selimiye, he argued that the former was designed to demonstrate the grandeur of load-bearing architectural elements, while the latter is the embodiment of quietness, calmness, elegance and inert expression.

Turgut Cansever’s primary concern was to combine architecture with ethics that entailed a quintessential overlap of religion, tradition, architecture and cultural identity on a sociopolitical axis in contemporary Turkey. Those who read his books or those who had the chance to meet him in person know well the endless optimism he had for the future. Thanks to his strong belief in ideas that have precedence over actions and the idea that what changes the world is the power of ideas, Cansever strived to find “true” ideas in architecture and disseminating them. His architectural practice and intellectual legacy have a huge impact on the new generations of educated middle-class conservatives of Turkey and will probably influence the next generation of architects in decades to come.

This article has first appeared in Daily Sabah on February 24, 2018.