I had graduated from my schools in Paris and was working as a journalist in 1996. Despite serious opposition from the Republican People’s Party (CHP), the representative of the status quo in Turkey since its conception, it had been 6-7 years since the first privately owned TV channel was established. After that, more privately owned TV channels started to emerge and emerge fast. A French journalist who worked for the weekly French TV magazine Telerama and was to go to Istanbul to write an article on Turkish television called me. I invited the journalist to my home office. I was opening Turkish TV channels one by one and was answering the questions of the journalist during evening news. At one point, the journalist suddenly turned towards me and said “It seems there was a recent coup in Turkey. Sorry, I guess I didn’t study Turkey that well; but, now I understand it.” I replied: “What makes you think of that? There hasn’t been a military coup in Turkey for 16 years.” The journalist was surprised and said “As I have seen many men with epaulets, I couldn’t think otherwise.” Even though I had issues with military’s intervention to politics, I then realized that we were inured to this situation and the military rule was normalized. It was a degrading feeling.

After the 1960 coup, the 1961 constitution, which is deemed as the most democratic constitution of Turkey was prepared. Those who prepared the constitution were the members of a group which made the decision to hang the prime minister and two other ministers after the 1960 coup. At first sight, it seemed like a constitution which was democratic and clearly defined separation of powers; however, in reality, it was also a constitution which was made by those who supported the coup and the junta. The spirit and the body of the constitution were disparate. The National Security Council (MGK), which was to increase its power with every change in constitution until the 2000s, was established with the 1961 constitution. As the military tutelage was already dominant and functioning at that time, its significance wasn’t immediately evident.

The military was the determiner of Turkey’s policies, both domestic and foreign. Even though it was already independent, the military established the military courts with the constitution made after the 1971 coup, becoming an institution that was completely out of the system. The MGK’s authority was increased with this constitution. The military tutelage branched out and started to extend its branches in every direction with every change.

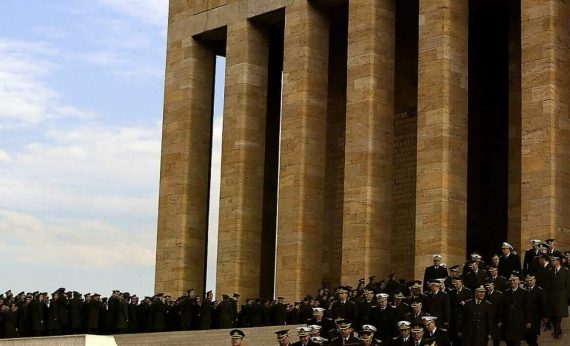

For those who have read about the said era from books, who were children during the 1980 military coup and who were in their teens in the 1990s, this was how Turkey seemed to be: On a long table, at one side the force commanders and the chief of general staff were sitting with all their majesty, while on the other side there were the president, a miserable looking prime minister and a couple of ministers. MGK meetings were frequent; they would start in the morning and journalists would camp right in front of the General Staff compound, waiting for the results of the morning while sharing information like “the curtain moved, a car came in, a car moved out.”

Most of the times, the declarations were made on evenings and the military’s new designs on civilian politics would make the news. Naturally, these visuals had only one meaning for the journalist who was from France; a country where the name of the chief of general staff isn’t known and where the army is deemed “mute” since the Dreyfus incident: a military coup! We had seen only a president who stood against this and he was Turgut Özal. Beside him, the system was functioning like clockwork; however, Turkey experienced two more military coups, as those who winded this clockwork machine wanted to do so, for some reason.

The foul-spirited but physically healthy constitution foresaw the foundation of a new institution which was the constitutional court. It was a seemingly crucial institution of modern democracy which would examine laws. As I have said, it was a seemingly democratic constitution; however, it didn’t function in the same way. The 1924 constitution that was made a year after the foundation of republic had a definition for the ideal citizen. It wasn’t easy to utter “Ne mutlu Türküm diyene” (How happy is the one who says I am a Turk). Everyone, regardless of their ethnicities had to say these words; yet, it still wasn’t easy for Turks as well, as all Turks weren’t eligible. They had to be Kemalists, secularists and originally Turkish. If their origins were any different, they had to just forget their origins.

Establishing a monolithic structure in a country which transitioned from a multilingual and multicultural empire to a nation-state wasn’t going to be easy. In fact, look at the past of those who remembered that they were Kurdish and established parties, of liberal, conservative or classical right-wing parties which had issues with the system that was based on the secular understanding of France’s 4th Republic. The constitutional court’s most important handiwork in between the coups was to close down parties which were deemed to be against the rigid tutelage system. While Turkey turned into a garbage heap of political parties, the tutelage system recycled these parties, allowing them to emerge with new names and new programs. If they went against the system once again, they would be closed.

To understand the extent of this, it’s enough to look at the numbers of right-wing parties and their leaders, along with Kurdish political parties. However, this wasn’t the only duty of the constitutional court. For instance, whenever the ruling party made a law on anything, ranging from agriculture to privatization, the status quo party CHP’s former leader Deniz Baykal would appeal to the constitutional court to abolish the law. Therefore, the main opposition party was an actor of a system which was deadlocked by the constitutional court. Applications of the party that did politics under the shadow of the military, that supported and was supported by the military was accepted for decades.

Recommended

According to the 1982 constitution, the decisions made by the MGK had to be prioritized by the government. As almost all presidents were of military background since the 1961 constitution, the presidency was deemed a safe position by the tutelage. Süleyman Demirel, who just couldn’t win against the military despite all his efforts, said “We knew that they [the military] would propose a general for presidency. We thought that we should choose a candidate with a military background instead.” He tried to be compatible with the system, as the opposite was impossible; indeed, when the most renowned constitutional lawyer of Turkey Ali Fuat Başgil became a presidential candidate, the henchmen of the tutelage had put a gun to his head, dissuading him.

The 1981 constitution had also topped the ceremonial parliamentary system of Turkey with a president which had unlimited power and gave the post a new duty: to determine the agenda of the MGK. This meant that the president of the tutelage system would determine the agenda and the elected government would have to implement the president’s decision.

On February 28 1997, during the coup which was deemed as post-modern by its perpetrator, Süleyman Demirel, one of the most important figures of the political right who had suffered because of the system, did what the military asked and preserved his presidential seat. The following president was a classical Kemalist and CHP supporter who sincerely believed in the system and used the authorities provided by the 1982 constitution to the fullest extent. He was not of a military background, but he was the previous head of the constitutional court. This system, this ceremonial parliamentary system functioned well in Turkey. However, there was a crisis when the Justice and Development Party (AK Party), which had become the government by itself through having the majority of the seats in the parliament, tried to elect the president.

Despite facing closure, attempts of junta intervention, the AK Party was able to stand tall because of strong public support. At the same time, the AK Party had initiated negotiations with the EU and passed many democratic laws from the parliament to fulfill the Copenhagen criteria. However, the Turkish democracy was wounded once again in those days. The tutelage system made it clear that all hell would break loose if Recep Tayyip Erdoğan became the presidential candidate. One of those who announced this threat was the main opposition party CHP’s then leader Deniz Baykal.

Erdoğan renounced his candidacy and made Abdullah Gül the presidential candidate in his stead. As Gül’s wife also wore a headscarf, he couldn’t be the candidate too! In fact, they have expressed that they would raise hell; however, the AK Party resisted and showed Gül as their candidate. The CHP alleged the election was unconstitutional and appealed to the constitutional court. The constitutional court knew what they had to do; the military had published a memorandum which detailed what kind of a president had to be elected!

With a scandalous reason for its decision, the constitutional court declared that the elections were invalid. There was a crisis. The AK Party sought to resolve this crisis and found a solution. The proposal foreseeing the election of the president by popular vote was brought to referendum and the people voted in favor of it. You know the rest; Gül was elected first and after his term Erdoğan was elected on the first round of elections by acquiring 51.8% of the votes.

On April 16, the constitutional reform which foresees a change in Turkey’s system of government is going to be voted on. If the people approve it, the ceremonial parliamentary system will be replaced with a type of presidential system. If you’re wondering whether the main opposition party which is the guardian of the old system is offering any alternative, they are not; they’re only saying that Turkey must be governed with a parliamentary system. The question is was there even a parliamentary system in Turkey to begin with?

Is Turkey completely free of issues regarding democracy? No, not completely. Yet, people have become experienced in such matters and they don’t believe that these issues will ever be resolved by the representatives of the status quo. Regardless of the result, everyone is sure that the crises of the imposed system will eventually be resolved by Erdoğan; not by the main opposition party.