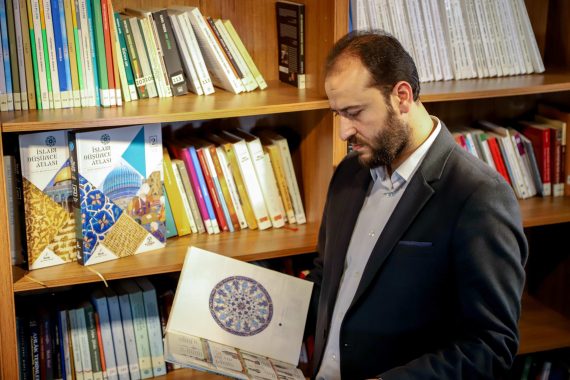

Following an intensive three-year preparation period, the Atlas of Islamic Thought project finally came to life. The project, which was led by the Scientific Studies Association (ILEM) and fully funded by the Konya Metropolitan Municipality, gave life to a new website and a three-volume encyclopedia, with the intention to bring back to life the significance and relevance of Islamic thought and philosophy to today. Assist. Prof. Ibrahim Halil Ucer of Istanbul Medeniyet University, the project coordinator, answered questions about the project.

What is the scope of the project and how did it come to life?

The Atlas of Islamic Thought is a project which came to life within ILEM with the support of the Konya Metropolitan Municipality Culture Co. It is a project of historical thought and literature, which was brought together with a broad scope of people, including historical researchers, software engineers and map engineers.

Within the scope of this project, an uninterrupted, dynamic and in-depth history of Islamic thought was suggested. This proposal is based on a new periodization, a comprehensive treatise on the evolution and transformation of scientific disciplines in the history of Islamic thought. In relation to every scientific discipline, scholarly, institutional, and architectural works are written down. Supported by extensive project-specific maps and graphics, the three year work led to an open-access website (www.islamdusunceatlasi.org), which includes interactive programs online, and a three-volume encyclopedia called the Atlas of Islamic Thought.

What has been your initial motive?

The history of Islamic philosophy and sciences were put to the periphery of the history of philosophy and were ostracized. However, Islamic cities were the capitals of global philosophy between the 7th and 17th centuries, while its languages were Arabic, Turkish, Farsi and Urdu. This era doesn’t exist according to current historiography of philosophy; it’s as if there was a millennium of silence. We have prepared this project to position Islamic philosophy to its rightfully earned place in the general history of philosophy. As long as we don’t position Islamic philosophy and sciences in the general history of thought, we won’t be able to regain our historical consciousness and to dare to think.

This era doesn’t exist according to current historiography of philosophy; it’s as if there was a millennium of silence.

How did you extract the history of Islamic thought? What were some of the challenges?

We faced two dilemmas. The first one was the ignorance of the Islamic philosophy in the general histories of philosophy and the second was the neglection of the post-Ghazali period by historians of Islamic philosophy. According to them, the history of Islamic thought begins with the 7th or 8th century and ends with the 12th or 13th centuries.

The history of Islamic thought is divided into two epochs: the pre-Ghazali era, which includes the Rashidun, Umayyad, Abbasid and Taifa, is deemed the heyday of Islamic thought, an Islamic Renaissance. Meanwhile, the post-Ghazali period, thus the scientific traditions which emerged in Seljukid, Ottoman, Timurid, Baburid and Safevid periods are regarded as an era of regression, dissolution, collapse, and decay.

Since the early 1900s, there is a dominant discourse that Islamic thought lived its heyday until Ghazali. There is a belief that Ghazali killed philosophical and scientific thought. The reason behind this discourse is the belief that only Greek elements within the history of Islamic thought are valuable. If it has traces of Aristotle or Plotinus, it is perfect and golden. The Atlas of Islamic Thought is an objection to this discourse. This is also an objection against the orientalist cultural offense exerted to the Islamic world for over a century.

What have you found through this objection?

We’re not only talking about lost periods, but about lost centuries and geographies. Every civilization builds itself with cities, art works, scientific and literary traditions, and institutional organizations. All of these components which create this unified structure are only meaningful within it. Today, this civilization that we hope to live in is fragmented and these fragments are scattered around. We’re living in a scattered home; yet, we know nothing about this home as our memory has been fragmented. Because we don’t have any idea about the whole that has been built by Islamic civilization, these scattered components have lost their real meanings.

Recommended

Because we don’t have any idea about the whole that has been built by Islamic civilization, these scattered components have lost their real meanings.

The most important function of the Atlas is to recreate this scattered whole through recollecting various historical, geographical and institutional facets, determine their meaning in relation with the big picture and to see this unified structure again. Meanwhile, we offer a holistic approach to the neglected geographical and cultural heritages of Islamic countries through historical maps. We also aimed to give cities like Merv, Bukhara, Samarkand, Delhi, Damascus, Mosul, Konya, Sivas, and Malatya the place they deserve in history – all of which were subjected to something that could be called geographical theft.

Is forgetting Seljukid and Ottoman thoughts related with the alphabet reform?

It definitely is related. While it’s a prominent reason, alphabet reform is not the only one. Muslims understood that the scientific revolutions reaching its climax in the West during the 18th century was a breaking point for history. However, instead of harmonizing the old and the new in a critical way, they relinquished the old along with its memory and adopted the new as a whole. We have been forgetting consciously for the last two centuries. Alphabet reform was probably the fatal blow.

Could you talk about your periodization of the history of Islamic thought?

We periodized it into four main eras. The 7th-11th centuries are called the Classical Era, 12th-16th centuries Renewal Period, 17th-18th centuries Self-Examination Period, while the 19th-20th centuries are called the Quest Era.

The Renewal Period is divided into two divisions within itself. The 12-14th century is characterized by the evolvement of methodologies and the formation of new classics. The 15-16th century is labelled as the Late Renewal Period and is characterized by the efforts of methodological integration. The Self-Examination Period is also divided into two within itself. The seventeenth century corresponds to the time period in which the scholarly accumulation so far produced in the Islamic thought tradition was examined with reference to the old (kadîm). However, the case in the eighteenth century was different in the sense that self-examination was done with regards to the new (cedîd) – taking into account the groundbreaking developments that appeared in the West.

You have mentioned lost cities like Mosul and Aleppo. We were forced to forget these lands and now they are being destroyed, one by one. Isn’t this rather meaningful?

We are unaware of the reality that cities like Mosul, Aleppo, Baghdad, Damascus, Bukhara, Samarkand, Khiva or Delhi are all essential components of our collective memory. When Daesh occupied the antique city of Palmyra, the European world reacted, as Palmyra is an antique Roman town and Europeans believe that it is part of their collective memory. Thus, they have allowed the Assad regime forces to recapture the city, despite having declared their, at least outward, enmity with the regime. Mosul and Aleppo are in ruins today, so is Damascus. Collective memory is tied to the space.

So, you mean without the spatial aspect, memory is harder to recall.

Exactly. We can achieve this only by putting the pieces together, reforming the whole and remembering as the motto of the Atlas of Islamic Thought says “reunite the parts, discover the whole.”

Professor Ucer, thank you very much for the interview.

Note: A Turkish version of this interview has first appeared in Gercek Hayat weekly magazine.