As Turkey has entered into the atmosphere of early elections, there is one crucial question that begs to be answered: Why does the opposition in Turkey fail to win elections?

In order to win an election, political parties are supposed to create the most inclusive identity. This involves political parties to steer the majority of societal demands to themselves and articulate these demands within their constitutive discourses. For instance, a political party that pursues liberal-democratic politics is to argue that social problems such as underdevelopment or discrepancy between the rich and poor or ethnic and religious discrimination, or the absence of rule of law could only be solved if society embraces liberal democracy. From this perspective, if a political party cannot win an election or hold on to power, this means that the identity it offers was not the most inclusive or that society does not find it persuasive.

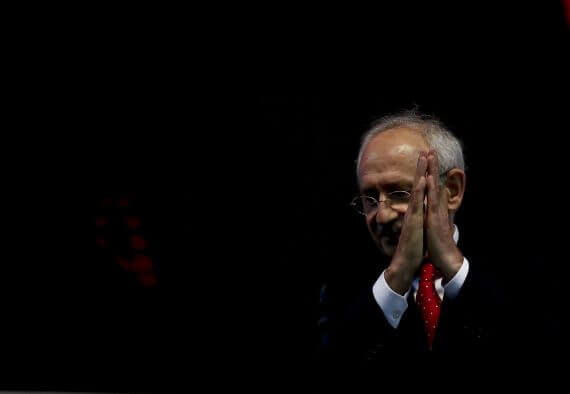

In Turkey the opposition, which is mainly formed by the secular-nationalist Republican People’s Party (CHP) and its constituents in society, suffers that shortcoming. The identity that the opposition offers, which is based on a secularist-nationalist discourse, is not that inclusive. This secularist-nationalist politics denies the demands of conservative and Kurdish sects of society, which constitute the majority of voters, at least 65-70 percent. Those demands are excluded on the ground that they menace Turkey’s long march to modernization and jeopardize the country’s unity and integrity.

Despite this, secular-nationalist politics fails to obtain sociological legitimacy. The equivalence between modernity and secular-nationalism played a central role for the Kemalist forces to sustain their political and international legitimacy in the pre-2002 period. In that period they held on to power by means of bureaucratic tutelage, yet suffered enormous democratic legitimacy. Due to these authoritarian policies, the Kemalists did not win a single election since 1950, when Turkey switched to a multi-party parliamentary system and held its first free elections in the Republican period.

Recommended

The opposition kept clinching on to its secular-nationalist politics even after the AK Party rule started in 2002. The AK Party strived to lay the ground for democratic politics in the sense of emptying the place of power. This process of democratization gradually alienated the Kemalist forces from the state. Once this process of alienation was completed around 2010, the Kemalist CHP became the opposition party in real terms. Hence, it has left aside its secular-nationalist politics, which was functional in sustaining the identification between the Kemalists and the state, and adopted the discourse of democracy. However, this shift has not yielded the expected results. CHP lost all elections – the parliamentary elections in 2011, 7 June 2015 and 1 November 2015, the presidential elections in August 2014, the referendum of April 2017, and the local elections in 2014.

There are two reasons for these series of failures. First of all, in order to win an election by democratic discourse, there has to be a situation where there is a strong identification and integration between the ruling power and the state (there are democratic and non-democratic ways of doing this). As long as the ruling power observe the basic principle of democratic politics which keeps the place of power empty – that means allowing the transfer of power through free elections and respecting the presence of opposition parties within a multiparty setting and agreeing to share power with them if the conditions require so – the discourse of democracy does not help winning an election. Since the AK Party has in general abode by the basic norms and rules of democratic politics, this “negative” form of democratic politics has not delivered the expected results.

Secondly, as noted above, democracy also requires producing the most inclusive definition of demos by absorbing the majority of societal demands in order to win an election. This constitutes the “positive” side of democratic politics. Failing in this results in losing the elections and holding on to power. The opposition has so far failed to put forward the largest and most inclusive identity. This requires bringing together either the Kurdish nationalists or the secular-nationalist sections of society on the basis of secular politics or its secular-nationalist sociology with the conservative-religious sections of society on the basis of a form of right wing nationalism. The former backfires due to persistent nationalism of its constituents whereas the latter results in nothing due to their hard headed secularist tendencies.

Therefore, the options before the opposition comes to be either to transform the secular-nationalist identity of its constituent in order to bring them together with other identity groups or find a new identity basis that transcends secular-conservative and Turkish-Kurdish nationalist fault lines in society. Failing in both leaves CHP with the option of making the country ungovernable. Sadly, this disruptive politics is what the CHP has followed for a while. And it seems that it will continue to do so.