In the last few years, Turkey has been going through a rather dynamic phase in higher education. Especially in the last ten years, the higher education sector experienced an impressive growth rate. As the increasing demand for higher education was not met by higher education institutions for decades, politics has intervened by pursuing the policy of founding new universities to increase the higher education supply. This meant that the massification of higher education, which took place in developed countries after World War II, could be experienced in Turkey first in the late 2000s. This also meant that Turkey must also struggle the problems brought about by the massification. Despite these problems, however, there are dazzling gains: obstacles to higher education were removed and schooling rates in higher education are steadily increasing.

According to the Global Competitiveness Report 2016–2017 by the World Economic Forum (WEF), Turkey is ranked 55th among 138 countries in the Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) and the country is ranked 17th in tertiary education enrollment. When compared to 2011-2012 Report by the WEF and the subsequent reports in the following years, it is seen that Turkey has been experiencing stable progress.

For the first time, the schooling rate of women surpassed men’s, due to women’s increased access to higher education. Similarly, the number of women academics within this period skyrocketed, surpassing the average of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA). The number of students in higher education is currently over 7 million. On the other hand, the number of international students and academics increased significantly. The internationalization of Turkey’s higher education is strengthening by the day and providing the opportunity to become a regional and global center for higher education. All of these are important gains for Turkey and now the time has come to deal completely with the problem of quality.

The tremendous growth in higher education raised questions about the quality of education; nevertheless, it’s not a form of growth that disregards the quality of education. These developments all took place in accordance with the existing culture of quality and this culture is being consolidated by the day. There is an increased awareness on the subject matter; the experiences of the past paved the way for healthy development, while also contributing to the culture of quality. Increased awareness, higher education institutions embracing the process and the quality assurance system are crucial, along with staff, students and the partners being a part of this culture of quality for the years to come.

Previously, higher education institutions in Turkey were accrediting their departments and programs in accordance with their own quality standards through international accreditation institutions. Similarly, institutional evaluations of higher education institutions were being handled voluntarily through the Institution Evaluation Program (IEP) of the European University Association (EUA); however, only a handful of universities were able to implement it. After the establishment of national quality associations under the umbrella of international quality agencies, the awareness for quality increased and the culture of quality started to spread. In this context, associations such as the Association for Evaluation and Accreditation of Engineering Programs (MÜDEK); the Science, Literature, Faculty of Science and Letters, Faculty of Languages, History and Geography Curriculum Programs Assessment and Accreditation Association (FEDEK); the Association for Evaluation and Accreditation of Medical Education Programs (TEPDAD), recognized by the Council of Higher Education (YÖK), and the Association for Evaluation and Accreditation of Educational Institutions and Programs of Veterinary Medicine (VEDEK) contributed heavily to the training of personnel specialized in quality assurance and the formation of a common understanding.

http://thenewturkey.org/with-brexit-and-the-trump-election-turkey-has-a-chance-to-draw-more-international-students/

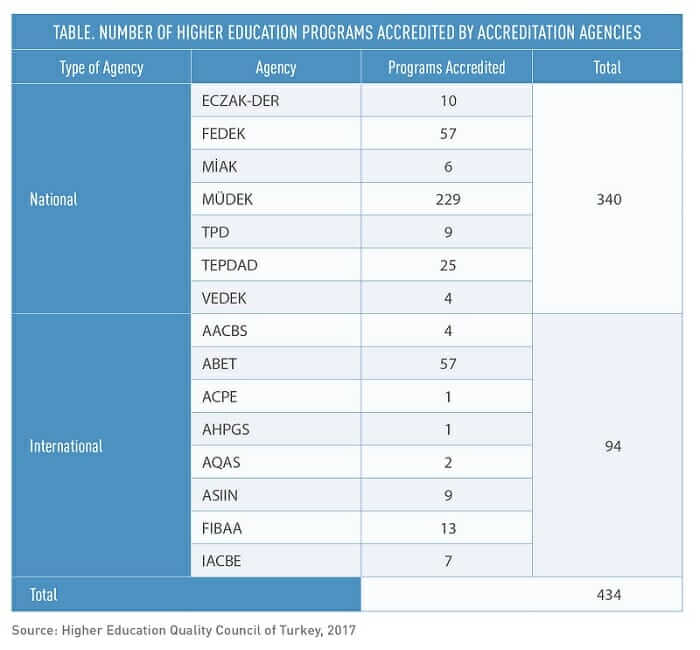

As the table below indicates, 340 higher education programs, excluding evening education programs, were accredited by these associations (April 2016). The increasing number of accredited programs of higher education institutions sets a level of quality which sets a standard for those programs that aren’t yet accredited, allowing them to share their experiences with other educational units within the same university. Moreover, the resistance of higher education institutions to external assessment is weakening, which is leading the way for the establishment of quality assurance systems.

Recommended

On the other hand, even though EHEA encourages higher education institutions to be assessed by other countries’ quality assurance agencies to establish trust between higher education systems, increase transparency and to set a quality standard, it can be seen that there are limitations within some European countries (Eurydice, 2012). For instance, higher education institutions in Denmark and Germany can only use other countries’ quality assurance agencies when the accreditation of the joint programs is in question. Similarly, in Austria, while public higher education institutions can use other countries’ quality assurance agencies, their private counterparts cannot.

In Moldova and Spain, the assessment of higher education institutions by foreign agencies is only possible after they have been accredited by domestic agencies. In Turkey, however, all higher education institution programs are free to accredit themselves from any existing quality assurance agencies, including both European and international ones. In this sense, while there are limitations for higher education institutions in some European countries to be accredited by international agencies, their Turkish counterparts are open to the assessment of all international agencies without a limit. As the table below indicates, 94 higher education programs in Turkey have been accredited by international agencies (April 2016).

EHEA, previously known as the Bologna Process, contributed to our higher education institutions and especially education programs by making them student-centered, while helping them to define the educational output in terms of skills and competences. All of these made it easier for the aforementioned quality associations to function and be a part of the system, along with increasing their activities.

After these experiences, the year 2015 witnessed two important cornerstones in terms of quality of Turkish higher education system. The Regulation on Higher Education Quality Assurance was prepared by the Council of Higher Education (YÖK) and came into force on July 23, 2015. The Higher Education Quality Council has been founded by the regulation. Similarly, with the joint effort of the Ministry of National Education (MEB), YÖK and the Vocational Qualification Authority (MYK), the Turkish Qualification Framework (TYÇ) was published, which was implemented on November 19, 2015.

The Higher Education Quality Council finalized its structuring and started to function. By December 2016, it started the international institutional evaluation program of the Turkish higher education institutions. This is an important cornerstone indicating that Turkey is entering a new era in higher education quality. While the higher education institutions previously could apply for institutional evaluation voluntarily through the IEP of EUA for exchange of a hefty sum of money, the new setting foresees the one-time external institutional evaluation of all Turkish higher education institutions within five years through the Higher Education Quality Council without any expenses. This process, analogous to the previous ones, will contribute to the development of the culture of quality within the Turkish Higher Education System, along with instilling this culture in the institutions and increasing awareness.

The institutional evaluation reports will be unique for each higher education institution and will include guidance to improve quality in the services they provide. In this sense, it won’t be accreditation, but a report which will encourage the higher education institutions to improve their services, while also assuring their quality. Therefore, it will function as an indicator which shows the strengths and weaknesses in quality assurance, and as a form of incentive to improve their status. As the institutional evaluation processes will result in the mutual learning of both the higher education institutions and evaluation teams, and help the spread of good examples in the county, it will also help the setting of a standard in the long-term in the Turkish higher education system. On the other hand, this process will eventually render the criticisms on lacking quality of higher education institutions irrelevant. Consequently, Turkish higher education system maintains its momentum and strives to continue the success stories despite the July 15 coup attempt.