G

old has long been considered a safe haven asset. Together with foreign exchange reserves and assets, it forms an integral part of a country’s reserves. Gold can facilitate trade, either in national currencies or in digital currencies. Moreover, wars, geopolitical tensions, financial crises, and high price volatility can all lead to increased demand for gold. However, recently, political impulses have played a relatively greater role than fundamental supply-demand or arbitrage dynamics.

Gold has recently been the main instrument of political revolt against the U.S.-dominated financial order. The dominance of the U.S. dollar is increasingly being challenged by gold and digital currencies as well as the growing trend to trade in national currencies. Many emerging or developing economies are building up their gold reserves. Even the BRICS countries are now working on a new gold-backed reserve currency.

Other key risk factors driving demand for this precious metal include, but are not limited to, rising geopolitical tensions in the South China Sea, the Middle East, South America, and the war in Ukraine. In addition, the tendency to avoid sanctions, the impulse to avoid other external influences, and the fact that the dollar’s role as an international reserve currency is increasingly being replaced by gold, the euro, and the renminbi all contribute to the same end. Moreover, rising interest rates and realized losses due to decreasing market value of the treasuries in reserves is also raising demand for gold reserves.

Despite rising interest rates, there is still a general increase in market demand for gold due to the risk of a banking crisis, geopolitical risks, and the financial turmoil. Gold should therefore continue to be used for hedging against catastrophic scenarios. For all these reasons, this most archaic—for some, even barbarous—instrument of trade and investment has today become a modern instrument of hedging and even of revolt against the financial hegemony of the U.S. dollar.

The rush to gold reserves

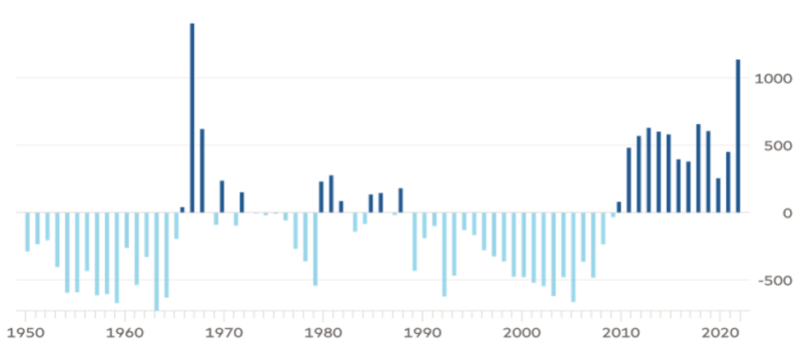

Central banks around the world are building up their gold reserves. In fact, these purchases are at one of their highest levels since the 1960s (Fig. 1). Central banks now account for almost a third of monthly gold demand. Meanwhile, most of these record purchases in 2022 were made by central banks of countries at odds with the West. Central banks are reducing their dollar and even euro reserves and replacing them with more and more gold.

Sizable gold imports are now a reality in most developing countries as they seek greater economic and financial independence. In this vein, a huge current account deficit challenge is also a certainty: exports are strong, but imports are even stronger. Energy and other commodity imports (such as gold) are massive in emerging markets. Thus, imports, energy, and broader commodity dependence have led to a new current account deficit spree.

As shown in Figure 1, according to the World Gold Council, gold purchases rose 152% year-on-year to a record 1,136 tonnes in 2022. This buying cycle is expected to continue this year. However, in order to keep gold reserves free from the direct influence or intervention of other major external powers, it is better to keep gold within one’s country.

Russia’s recent experience of increasing its gold reserves is a good example. Russia has been gradually increasing its reserves for a long time, doubling them to $640 bn in the last five years alone. Especially since the annexation of Crimea in 2014, Russia has consistently reduced its dollar-denominated reserves and has tripled its gold reserves.

Brazil and France are also well known for their criticism of over-reliance on the U.S. dollar for trade and financial transactions. Many experts believe that countries and companies alike are now too dependent on the U.S. dollar as their main currency. Some, such as French President Macron, have even called it a “sovereignty issue.” EU members such as Poland and Hungary, two of the largest Eastern European countries, have also recently increased their gold reserves.

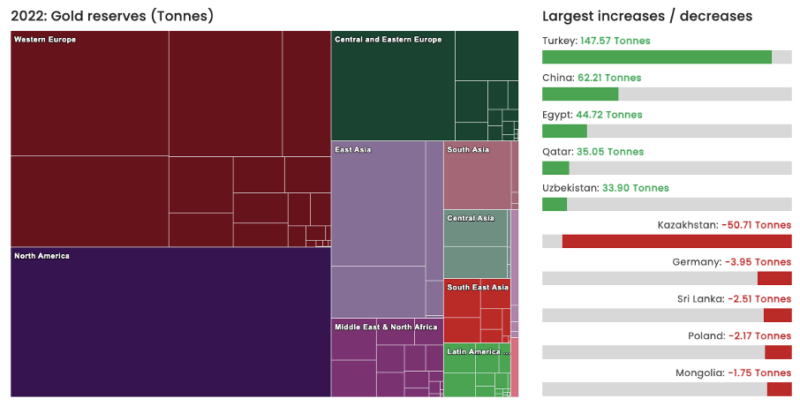

Indeed, major continental European countries such as France, Germany, and Italy, already hold around 60% of their reserves in gold (Fig. 2). Many others are already accumulating huge amounts of these gold reserves. Turkey, Germany, and Russia (even China and Iran) are steadily increasing their precious metal reserves as an independent tool against the financial dominance of the U.S. dollar.

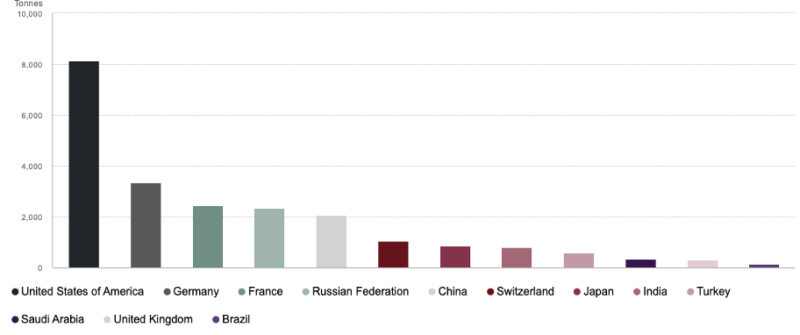

Perhaps a similar idea was behind the gold reserves that Turkey has built up or withdrawn from the UK and the U.S., especially in the last 10 years (Fig. 2). Thanks to its recent attempts, Turkey is currently pushing for a place among the top 10 countries in the world in terms of gold reserves (Fig. 3).

Turkey’s gold reserves

Turkey has been accumulating gold reserves for a long time, mainly, among other things, in response to rising geopolitical tensions and increasing efforts to pursue an independent policy. According to the World Gold Council, the Turkish Central Bank has been accumulating gold reserves in a continuous cycle for at least the past few years. Meanwhile, Turkey has also been withdrawing its gold reserves from the U.S. and the UK. Today, as the importance of this precious metal has begun to grow, the value of these initiatives is clear.

Reserves are rising fast. Turkey has increased its gold reserves by 148 tonnes in 2022 to a total of 542 tonnes by the end of 2022 according to data from the World Gold Council. They bought another 30 tonnes of gold reserves in 2023 and as of the first quarter of 2023, has a total of 572 tonnes. Nearly a third of all its reserves (34%) are gold. Central Bank of Turkey (CBRT) statistics from June 2023 show that the Turkish Central Bank had $67 billion in foreign exchange reserves and $41 billion in gold reserves.

However, an extraordinary sale of more than 130 tonnes of gold to meet domestic demand in the second quarter of 2023 should also be noted. Though, thanks to its recent bullion moves, Turkey is closer today (more than ever) to being among the top 10 countries in gold reserves (Figure 3). The withdrawal of gold reserves from abroad, on the other hand, had been on the agenda in Turkey since at least the 1960s; however, it held the potential to leave the country in deep political turmoil.

Other developing economies

The sanctions against Russia have surely led to great concerns about where to keep international reserves, especially among the central banks of countries that are not aligned with the West. The sanctions following the war in Ukraine froze almost $300 bn of Russian reserves held abroad. Russia was able to use its huge gold reserves even during the sanctions in 2022, but most other international reserves were frozen. If these reserves were in bullion and held at home, they would not have been affected by the sanctions.

Following the invasion of Crimea, Russia has made an even more assertive attempt to diversify its reserves and other countries may follow suit. This de-dollarization trend, or shift away from U.S. assets, could in turn have major implications for the role of the U.S. dollar, its value relative to gold and other currencies, and its impact on the global economy.

Another example is China, which has increased its gold reserves to more than 2,000 tonnes for the first time in history. India is the world’s number one gold buyer with Indian consumers accounting for almost 20% of global demand per annum. China, Russia, and India are building up huge gold reserves. Together, these BRICS economies are making no secret of their ambition to find an alternative to the currently dominant U.S. dollar and are even looking for a new gold-based global reserve currency.

Recommended

India and China are at the forefront of global demand for both silver and gold, and are shouldering the gold imports. For example, China’s gold imports rose by 16% (or 555 tonnes) in the first half of 2023. This huge demand makes sense, as the post-WWII dollar-based Bretton Woods system was also built on the fact that the U.S. at the time held more than 70% of the world’s official gold reserves. More recently, many other Asian countries have also increased their demand for gold.

Nine of the top ten developing economies are either challenging or not aligned with the West. Many other Middle Eastern and Central Asian economies are also active buyers. Kazakhstan, for example, has been building its reserves since, at least, its independence. The left-wing Lula government in Brazil, countries such as Turkey and Iran, and Malaysia are all strong supporters of these alternative currency ideas. This also shows the value of Turkey’s recent attempts to build up its gold reserves.

The global outlook

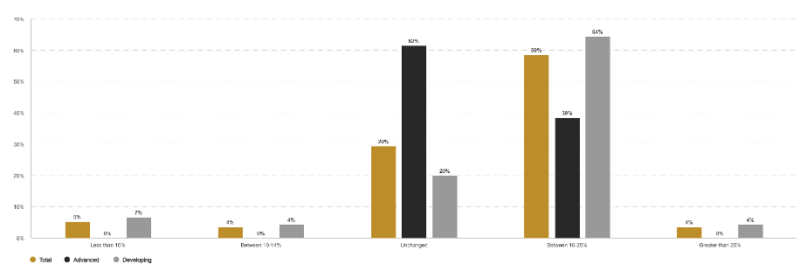

According to the 2023 Central Bank Gold Reserves Survey by the World Gold Council, the historic trend of gold accumulation in 2022 continues in 2023 albeit to a limited extent: 24% of central banks are inclined to increase their gold reserves further within a year and most are pessimistic about the role of the U.S. dollar as a reserve currency; 62% of central banks believe that gold is likely to play a much greater role than other reserve currencies.

Meanwhile, 59% of central banks—particularly those in developing countries (64%)—believe that between 16% and 25% more reserves will be held in gold over the next five years (Fig. 4). Moreover, more than 70% of central banks believe that global central bank gold reserves will increase within a year.