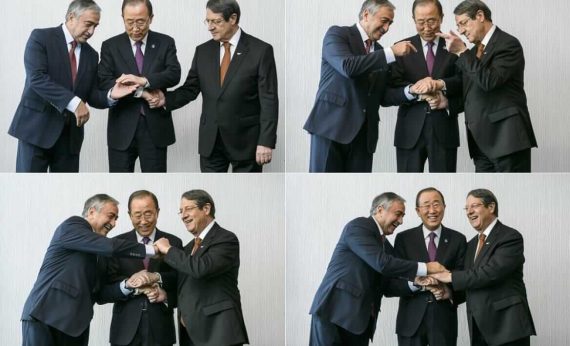

The date was May 15, 2015. Greek Cypriot leader Nicos Anastasiades and his Turkish Cypriot counterpart Mustafa Akinci had just announced the resumption of peace talks in the divided island of Cyprus. As the two posed for the press, none looked happier than the man who had brought them together, Espen Barth Eide, the UN’s envoy to the island.

The Norwegian diplomat’s ear-to-ear smile gave hope to over a million people on both sides of the divide. It was a hope they were all too familiar with, that had been given to them time and time again for over 40 years, only for it to be taken away from them. Barely a year had passed since they saw Anastasiades and Akinci’s predecessor, Dervis Eroglu, declaring their commitment to reunite the island under a bi-zonal, bi-communal federal system. Eight months later, the talks were off again due to disagreements over drilling for offshore natural gas.This did not help alleviate the trauma of 2004, when a plan proposed by then-UN Secretary General Kofi Annan to reunite Cyprus failed. Although Turkish Cypriots had approved the plan in a referendum held in the breakaway Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, Greek Cypriots in the internationally recognized Republic of Cyprus rejected it. As a result, Cyprus entered the European Union as a divided country.But this time there was something different in the air. Standing before an audience of hopeful onlookers were two leaders, both eager to end the stalemate, and an incentive for both the people and the international community to support them in their quest.

What was that incentive? Of course, natural gas. The discovery of hydrocarbons under the eastern Mediterranean seabed completely changed the dynamics of the on-again-off-again Cyprus peace talks. Its discovery particularly delighted the European gas market, which was long looking to diversify its imports away from Russia. Considering the most feasible supply route from the eastern Mediterranean to Europe would be building pipelines through Turkey, the EU had more reason to encourage both sides in Cyprus to sit down and come to an agreement.

A solution to the Cyprus problem would not only bring benefits to the EU, but would also give the economy of Cyprus a much-needed boost. It would also allow other regional players, such as Israel and Egypt, to cash in on the gas bonanza and enjoy better ties with Turkey. As for Turkey, a satisfactory deal would pave the way for the withdrawal of troops from the island, which would speed up its EU accession process.

So, Akinci and Anastasiades wasted no time. They started by ironing out differences in the basic areas of contention, making smooth and steady progress in an atmosphere of warm enthusiasm. But there was a huge elephant in the room that the two leaders were ignoring – the question of how the land itself would be divided.

Now, as the two sides begin to tackle the main points of disagreement that have repeatedly led to the collapse of talks in the past, the mood has suddenly changed.

On November 22, the talks hit their first major snag since they had resumed when Akinci and Anastasiades left two-day meetings in Geneva without an agreement on territory.

Currently, Turkish Cypriots control around 36 percent of the island. The Turkish Cypriot side offered a concession of 7 percent, which would bring their territorial control down to 29 percent. The Greek Cypriot side, on the other hand, demanded an extra 4 percent, leaving them in control of 75 percent of the island. The demand of the latter included all of the Guzelyurt (Morphou) district, the return of Kapali Maras (Varosha) and the establishment of a canton in the Karpaz (Karpasia) peninsula.

Recommended

The Turkish Cypriot side, however, seems keener on compensation payouts than drastically changing borders and demographics. Under any deal, the Turkish Cypriot side will already have enough trouble deporting some 80,000 migrants back to Turkey, which includes the children of migrant families who were born and raised on the island. They too will require compensation.

Having failed to reach an agreement in November, the two sides are expected to submit new maps in the next meetings in Geneva on January 9, 2017. Three days later they will be joined by the three guarantor states – Turkey, Greece and the UK – to discuss the issue of guarantorship.

Both Greece and the UK have previously stated their willingness to waive their guarantor rights. The Greek Cypriot administration has also demanded a complete pull-out of Turkish troops from the island. But the Turkish Cypriots oppose the complete withdrawal of Turkish troops. Turkey’s stance, meanwhile, remains ambiguous. If offered the right incentives, such as greater integration with the EU or the financial benefits of hosting a pipeline, Turkey may forgo its guarantor rights, or settle for a military base on the island, similar to the British bases.

In many ways, the fate of Cyprus partly depends on Turkey’s relationship with the EU. These relations took a turn for the worse recently when the European Parliament condemned Turkey for its crackdown on a network of state infiltrators who stand accused of being behind a failed coup attempt in July. Greece’s recent refusal to extradite fleeing coup plotters to Turkey also hasn’t helped.

Likewise, a rapprochement between Turkey and Russia following almost a year of strained ties presents its own problems. With Moscow and Ankara deciding to push ahead with the Turk Stream pipeline, which will pump gas from Russia to the Turkish-Greek border via the Black Sea, it is likely that any pipeline built through Turkey from the eastern Mediterranean will join the same network. This means that any gas Europe seeks to import from the eastern Mediterranean or Central Asia will be mixed with Russian gas as well. So much for Europe cutting off its dependence on Russia.

Low global crude oil prices also risk putting off potential investors from approaching the eastern Mediterranean reserves. Energy giants must first be convinced that exploring, exploiting and exporting natural gas from the area will be profitable. So far, the reserves found in Cypriot waters are not enough to economically justify such investment, which means it would need to be combined with Egyptian and Israeli reserves. But in a region already plagued by political instability, investing in the eastern Mediterranean may prove to be a risk no company is willing to take.

As the gas fueling these peace talks begins to run low, Eide’s inspiring grin is gradually turning into a frown. Eide himself is now warning of a “deterioration of trust” and a “hardening of positions” among ordinary Greek and Turkish Cypriots. For many Cypriots, these talks are a last chance for peace on the island. If they fail, it is unlikely that anyone will accept the continuation of the status quo.