C

hina’s lending practices towards developing countries under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) have come under heavy criticism from the U.S., which has dubbed it “debt trap diplomacy.” China’s critics argue that it is causing unsustainable debt by financing mega-infrastructure projects whose economic viability is not guaranteed.

Again, according to its critics, some of the implications of the BRI appear to be that Chinese loans will eventually cause developing countries in the Global South to default on their debts, allowing China to take control of strategic assets such as ports, railways, power stations, etc.

China rejects such discourse, claiming that it is criticism invented to discredit it. Referring to the BRI, China portrays itself as a benevolent development partner of developing countries in the Global South.

China argues that its development finance has created a niche for developing countries that lack sufficient national savings to finance their own development investments. The ease of borrowing compared to Western institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) strengthens China’s international reputation.

In fact, China has become the “lender of first resort” for developing countries in the Global South. China emphasizes its role as the largest contributor to the Global South and temporarily suspended interest payments to developing countries canceling 23 interest-free loans to 17 African countries during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Brad Parks, executive director of AidData at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute in Williamsburg, Virginia, told AP News that China’s interest-free loans to Africa were mostly from two decades ago and amounted to “less than 5% of the total” loans it has given to Africa. In addition, Harry Verhoeven, a senior research scholar at Columbia University, told Voice of America that China has forgiven the 23 interest-free loans to African countries in order to counter the West’s debt-trap diplomacy discourse.

How China’s development finance works

Between the 1950s and 1970s, due to the Cold War context, China’s aid was based on the strategic purpose of funding sympathetic movements and governments. From the 1980s onwards, its development finance started to undergo a paradigm shift that prioritized China’s own economic development. In the newly emerging paradigm, China’s development finance rested on export credits and loans tied to the global expansion of state-owned enterprises (SOEs). The China Development Bank (CDB) and the Export-Import Bank of China (China Exim Bank) became the pioneering development financiers within this process. SOEs financed developmental investments overseas to stimulate external demand for Chinese goods, services, and capital within the framework of the BRI in a profit-seeking manner. The scope of overseas financing by SOEs covers the construction of railways, ports, and power plants.

What differentiates Chinese loans from those of the West and international organizations such as the UN, the World Bank, and the IMF are as follows:

Chinese SOEs’ financing often begins with Chinese SOEs lobbying the government of developing countries to provide finances for the developmental investments and win the relevant contracts.

China’s SOE-led development finance proceeds through the developing countries’ pursuit of finances to materialize their developmental investments, which contrasts with the conventional approach by the West and international socio-economic institutions which remain simple donors.

An article by Chatham House has argued that the loose governance of overseas financing by Chinese SOEs and banks has created a set of flaws such as closed tendering which are the result of the lobbying activities of Chinese SOEs for overseas projects initiated by developing countries’ governments. The article also claimed that the interplay of Chinese state-owned enterprises’ commercial interests and the policymaking of the political elites in recipient countries makes project viability assessment problematic.

Chinese loans vs. Paris Club’s loans

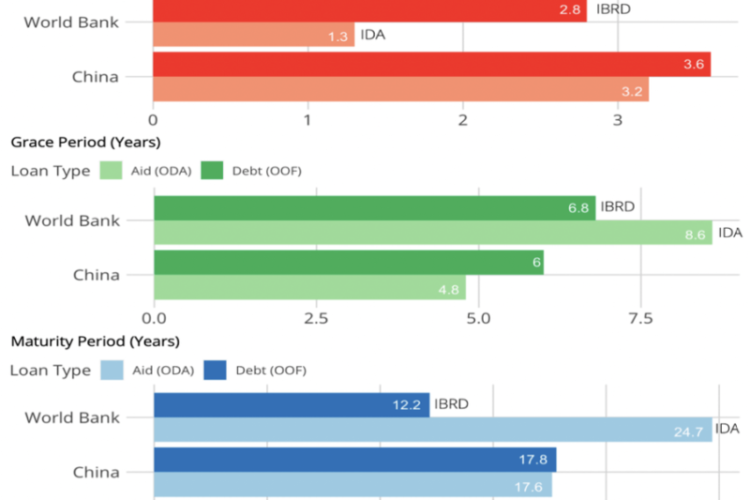

China’s loans have higher interest rates with shorter grace and maturity periods compared to concessional loans by the World Bank and the Paris Club which makes Chinese loans harder to repay. The Paris Club (or Club de Paris), established in 1956, refers to an informal group of creditor nations whose main objective is to find solutions for various debt repayment issues faced by debtor countries.

In order to mitigate the risk of default posed by the high-interest loans, in some cases, China opts for the collateralization of assets. In Southeast Asia, the Global Career Development Facilitator dataset detected 54 collateralized debt-financed loans, approximately 95% of which was allocated to strategic sectors such as energy, mining, transportation, and communication. What is more, Brad Parks, executive director of AidData, has also discovered that Chinese state-owned enterprises were including clauses in some contracts that required borrowing countries to deposit U.S. dollars in secret escrow accounts. Thus, China’s risk mitigation strategy for debt-financed foreign loans has given rise to the Western-orchestrated discourse of “debt trap diplomacy.”

China often channels its loans to developing countries through Chinese SOEs, joint ventures, and banks, keeping them off government balance sheets. The country’s development finance relies on the commercial interests of SOEs, with government-to-government loans accounting for a small share of Chinese lending.

AidData has revealed that China does not report half of its loans to developing nations in debt statistics. The commercial contracts by Chinese SOEs with the governments of developing countries include confidentiality clauses, precluding borrowers from revealing the content.

Configuration of Chinese loans to the Global South

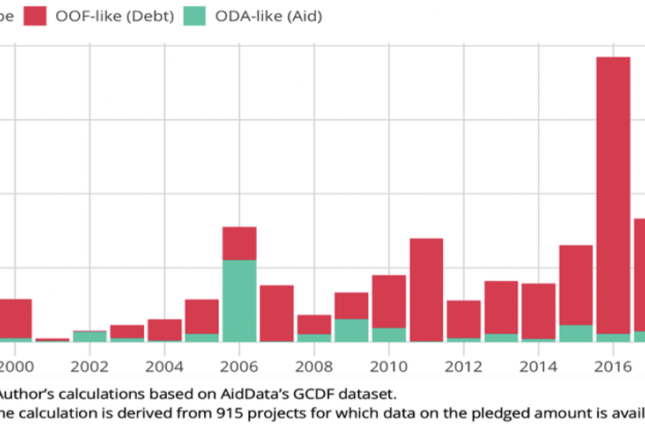

China’s debt-financed loans heavily outweigh aid-financed loans. Figure 2 demonstrates the configuration of China’s foreign loans to developing countries in Southeast Asia. The findings are in line with the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development’s definition of flow types, namely “official development assistance” (ODA) aid and “other official flows” (OOF).

The drastic change in the aid-debt ratio that started in the early 2010s reflects China’s tendency to provide loans with high interest rates at the market level rather than aid with either zero or concessional interest rates. China’s rising debt-financed loans relative to aid-financed loans to developing countries also coincided with the introduction of the Belt and Road Initiate in 2013. This fueled the Western perception of China pursuing a grand strategy of economic statecraft in the Global South.

How China’s “debt trap diplomacy” is playing out in the Global South

A typical example of how China’s “debt trap diplomacy” is unfolding can be observed in Sri Lanka with its Hambantota International Port often cited as a leading case against the Belt and Road Initiate.

Sri Lanka

Critics have claimed that China’s Exim Bank stepped into financing the construction of a mega-size port at Hambantota, Sri Lanka deliberately without assessing the debt sustainability of civil war-torn Sri Lanka and the economic viability of the project.

Concerning China’s lending practices to Sri Lanka, journalist Maria Abi-Habib stated in an New York Times article that “every time Sri Lanka’s president, Mahinda Rajapaksa, turned to his Chinese allies for loans and assistance with an ambitious port project, the answer was yes.” Building on that, critics argued that China overwhelmed Sri Lanka with an unsustainable debt stock, leading the country to default on its sovereign debts in 2022, and then leased the strategic port of Hambantota in exchange for debt relief for 99 years.

With China’s reluctance to forgive debt repayments, Sri Lanka’s economic situation is grim: half a million jobs in the industrial sector were lost, inflation hiked up to 50%, and more than half of the Sri Lankan population has been plunged into poverty.

However, an opinion article in The Atlantic opposed this take on China’s “debt trap diplomacy.” It argued that Sri Lanka defaulted on its sovereign debts due to the political upheavals in Sri Lankan politics and Western capital markets’ lending to Sri Lanka which comprised 40% of its foreign debts.

Recommended

Zambia

As a landlocked country of 20 million that appealed to China’s state-owned banks for the financing of the construction of dams, railways, and highways, Zambia serves as a case study of the dire outcomes of China’s “debt trap diplomacy.” Chinese foreign infrastructure investments brought about a boom in the Zambian economy, while also increasing Zambia’s foreign interest payments to such an extent that the country was forced to cut welfare payments. In 2020, the refusal by a group of non-Chinese lenders to suspend interest payments on loans caused a shortage in Zambia’s foreign cash reserves.

With the remaining scarce foreign cash reserves, Zambia was unable to procure commodities such as oil and natural gas adequately. In November 2020, it suspended interest payments and defaulted on its sovereign debts. Researchers looking into Chinese loans to Zambia found that a third of Zambia’s foreign debts, amounting to $6.6 billion, was from Chinese state-owned banks. China’s Western critics ascribed the situation to its unconventional lending practices such as confidentiality and reluctance to forgive a portion of sovereign debts.

The aftermath of Zambia’s debt crisis was that inflation rose to 50% and unemployment reached a record high. Additionally, Zambia’s national currency (Kwacha) has suffered 30% devaluation in the last seven months. According to U.S. estimates, the number of Zambians who couldn’t afford to buy staple foods in 2023 tripled, reaching 3.3 million. Marvis Kunda, a 70-year-old blind Zambian woman, told AP news, “I just sit in the house thinking what I will eat because I have no money to buy food.” “Sometimes,” she went on, “I eat once a day and if no one remembers to help me with food from the neighborhood, then I just starve.”

In addition to Zambia and Sri Lanka, several developing countries in the Global South, such as the Maldives, Angola, Pakistan, and Laos, which have relied on Chinese loans, are on the verge of defaulting. This has given rise to speculation that China is deliberately pursuing economic statecraft to establish a Sinocentric world order in the Global South. On the other hand, given the recipient-driven nature of China’s development finance, it is debatable whether it is indeed diplomatizing the debt trap.