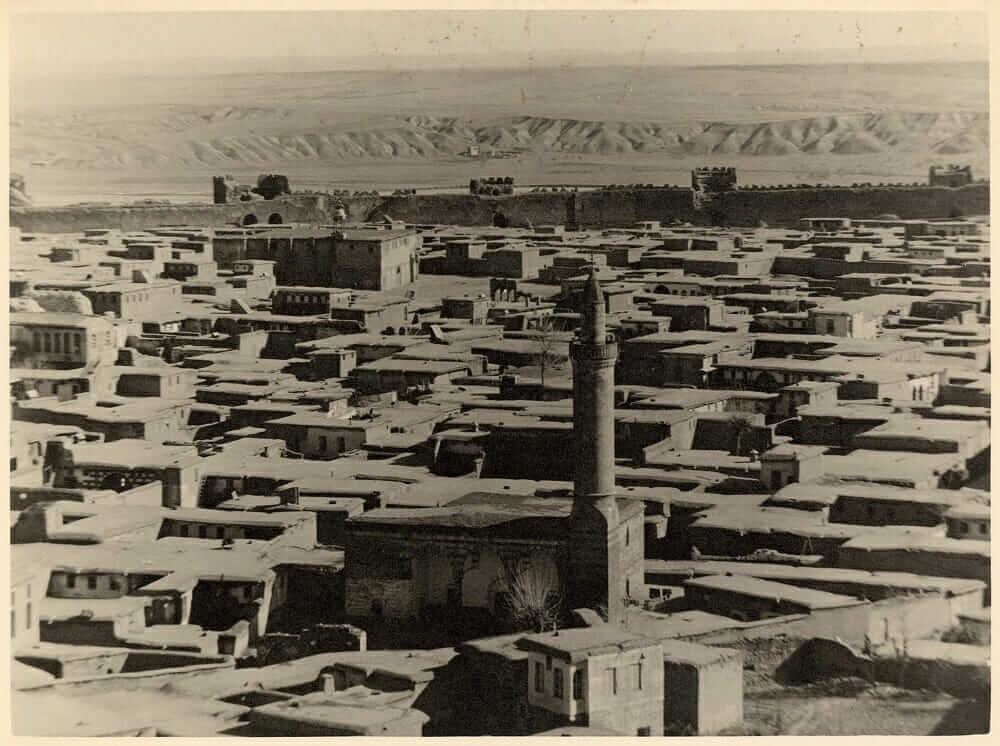

The reconstruction of historic cities has become entrenched in the Turkish political agenda due to security operations against the PKK terrorists in the Sur district, the ancient heart of Diyarbakır, in the winter months of 2015-16. Out of 120,000 residents, one quarter flew from the city, and the city’s historic legacy was heavily damaged. The social geography of the town has changed, and almost no one who returned home found the same home. A corollary of the material loss was the eradication of the signs and symbols of the childhood of the Sur residents.

Both the spatial and temporal dimensions of their collective memory turned into an empty sheet. All this was caused by the city fights that erupted after PKK forces made Kurdish majority cities the battleground for their alleged “self-rule” and “self-defense.” In so doing, the PKK tried to install itself as the “guerilla” fish in the sea of the Kurdish people, but failed to garner the support of the people and instead came into direct collision with the forces of the state. The end result was a fatal mistake for the PKK.

Recommended

The devastation of an historic city with an unplanned urban landscape and uncontrolled growth, including poor and non-developed urban slums, has brought with it new challenges as well as opportunities. Europe saw a great renewal and reconstruction of its historic cities after World War II. It supplied the builders with ample chances for creating cities equipped with modern streets, sanitation systems and innovative lodging. City planners, composed of miscellaneous scholarly disciplines like social and urban history, geography, architecture and town planning and political science, created functionally differentiated separate zones of housing, industry, culture, government and recreation. This way of reimagining Europe’s cities was common to both fascist and democratic countries.

Needless to say, urban reconstruction is a complex task with enormous potential for conflict that policy-makers have to tackle.

Needless to say, urban reconstruction is a complex task with enormous potential for conflict that policy-makers have to tackle: the clearance of the rubble and debris, financing the renewal project, the allocation of building material and labor, the extent of the possibility of historic cities being amenable to urban renewal during reconstruction, the creation of new streets and social amenities, the possibility of planning the city with functionally distinct zones in order to keep housing, commerce, industry and culture separate, deciding about the population density, the dilemma of building historic cities with a modern conception while keeping its traditional fabric intact, and the like. On top of all, there are two crucial questions: Who will make decisions for the city? The central government, the local town authorities, or private individuals? And how will priorities be determined vis-a-vis urban needs?

All of the queries listed above inform the debate sparked by the Sur Renewal Project (Sur İhya Projesi) initiated by the AK Party government. The Council of Ministers took the decision of “urgent expropriation” of 6,300 parcels scattered along 15 neighborhoods of Sur, which included the building of the Sur Municipality, some hotels, and the Cemil Pasha Mansion in March 2016. This decision was contested by the Diyarbakır Bar Association before the Higher Administrative Court (Danıştay) and is still awaiting a final decision. Former Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu had announced the Sur Renewal Project in Diyarbakır on April 1, 2016. According to what Davutoğlu said, the project will be based on the consent of, and reconciliation with, the local residents. The starting point of the project is UNESCO’s 2015 decision, which placed the city within the scope of World Heritage Sites, and the 2012 Reconstruction Plan for Conservation that involved both the central government and the Diyarbakır Greater Municipality as its executive partners.

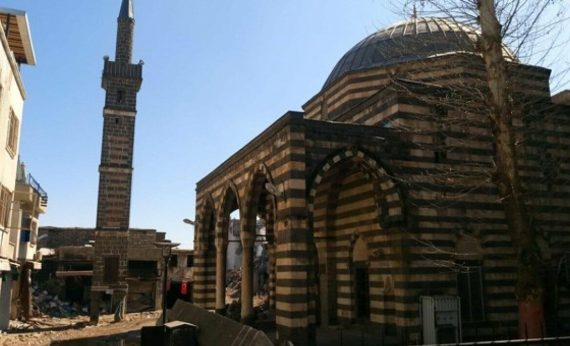

Rebuilding Sur while retaining its traditional fabric is an indispensable element of the project. The participation of Sur residents in the relevant decisions throughout the process would be taken as a must, and their ownership rights would be protected. Inner Sur would be restored in accordance with its multi-faith and multicultural character, and be organized as a tourist attraction. The facade of houses in Gazi Street, the main street of Sur, will be renovated by using Diyarbakır’s local and historic basalt stones. “We’ll rebuild Sur so that it’s like (Spain’s) Toledo: everyone will want to come and appreciate its architectural texture” said Davutoğlu. However, the pro-PKK Diyarbakır Municipality and the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) argued against the governmental discourse of “renewal of the city by keeping its history intact.” Let’s go over these arguments and to which degree they can be substantiated.

During the period of multi-party democracy, no democratic government resorted to the forced deportation of the Kurdish people. Democracy is not amenable to forced social engineering. The forced displacement in the 90s, and other forced settlement policies were all enacted under military rules. Therefore, the argument that the rebuilding project for Sur envisions a change to its demographic structure by allowing and encouraging non-Kurds, especially Arabs, (possibly Syrian emigrants) politically unsympathetic to Kurdish nationalists to occupy the district has no relevance whatsoever. Most of the refugee camps established for the Syrians are not situated inside the Kurdish majority areas, and not all of the refugees are Arab. Therefore, the claim that through various bureaucratic and financial means, the poor Kurdish residents who fled the city will be prevented from coming back has not materialized and has proven to be merely ideological propaganda. The government’s concern is to create public places to comfortably live, not to unman the district and turn it into a well-protected high security place, a sort of open prison, as has been suggested. Pushing poor people from where they live and replacing them with more affluent people may indeed be one of the most common way to develop desirable urban areas. However, the government’s declaration that no right-holder in Sur will be pressured to agree to an option that they do not want has publicly falsified this assertion.

The government’s concern is to create public places to comfortably live, not to unman the district and turn it into a well-protected high security place.

Similarly, the claim that the Project will ruin the historical-cultural texture of the city and its collective memory has no relevance, given the political and civilizational imagination inspired by the “Toledo model.” Sur was already the commercial heart of the city and there is no sense in arguing that “more trade and less housing” is something undesirable. The fact that TOKİ, the government’s housing and reconstruction agency, was declared not to be a constituent of the rebuilding in Sur, and that every building will be treated on a case by case basis, both in terms of ownership rights and architectural features, refute the allegations of “gentrification by military force” and “economic opportunism.”

To be sure, the rebuilding process will be based on an urban plan more amenable to state security control, and this is legitimate to the full. The Toledo model seems to well reflect the multicultural character of the city while paying attention the Seljuki-Ottoman cultural imprint, aiming not to conceal but to expose the Muslim heritage, in contrast to the HDP municipality which pushed this legacy to the back under the pretext of “multiculturalism.”

It is obvious that the rebuilding process secures a fresh opportunity for the AK Party government to reinforce its political legitimacy. The declaration of the region as “a risky area,” and accordingly, taking the decision of “urgent expropriation” indicate the government’s intention not to make Sur a habitat for the rich but to create a safe haven both for the state and for Sur dwellers in commercial, cultural and security terms.

All of the arguments against the project have proven to be groundless, given Davutoğlu’s statements regarding Sur, with the declared model for the renewal being the city of Toledo, an ancient multicultural city rebuilt after the Spanish Civil War. The non-involvement of TOKİ in the reconstruction process, the adoption of the pillars of the UNESCO World Heritage Site and the 2012 Reconstruction Plan for Conservation as the obligatory framework for the renewal, the participatory character of the process and the declared sensitivity of the government for the retention of the historic city while paying enough attention to modern technical facilities, the involvement of not only architects and engineers but also art historians, anthropologists, sociologists, urban designers and social policy experts, all combine to create hopes for the rebirth of a devastated city out of love and respect for historicity, multiculturalism, democratic participation and, without a doubt, a reemergence of the feeling of security for life, liberty and property.