The Jameel Prize is ‘an award for contemporary art and design inspired by Islamic tradition’ and is currently on view at the Pera Museum until August 14th 2016. This is the fourth edition of the award and exhibition which is organized by the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and the organization Art Jameel.

The exhibition is an interesting and partially successful presentation of Contemporary Islamic Art. The biennial event looks to fill a void by creating greater access and visibility to the growing ‘genre’ of Contemporary Islamic Art which in recent years has seen a number of artists from Iran and Pakistan in particular create work which is indebted to classical techniques and subject matter from the Islamic world while making use of contemporary materials, spaces and themes. Until now their outlet has been mostly galleries in New York City, London and Dubai where the context of the work is usually framed as contemporary ‘Iranian’ or ‘Pakistani’ rather than Islamic while larger Museum collections in North America and the UK occasionally add a work to their vast and important historical collections of Islamic Art to create a new dynamic to the curation.

Line

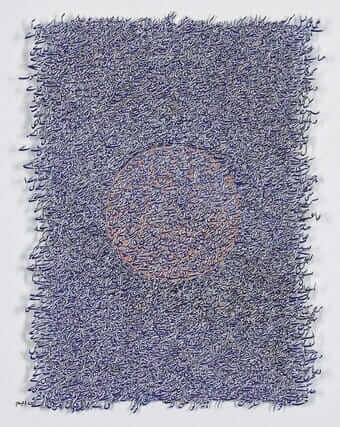

Pakistani artist Ghulam Mohammad (who won the prize this year) crafts meticulous collage works by cutting micro-sized Urdu text from old books and creating a visually poetic whirlpool of re-purposed non-narration. He is a graduate of the famous department of Miniature Painting at National College of the Arts in Lahore and the similarity to the Mughal genre shows when the words flow freely off the page and border. Both endless and finite, animated and dense- some of the works such as Gunjaan also play with open vacuums of space.

British artist David Chalmers Alesworth spent over 20 years in Pakistan and his work is interesting for its thematic use of carpets and gardens. The conceptual thrust behind his work on show here is the back and forth influences in carpets and gardens first from the Islamic world to Europe and then the other way around in the 19th century. Hyde Park Kashan 1862 takes an early 20th century carpet from Kashan, Iran and sews a transparent-like outline of Hyde Park (London) from an 1862 map. The scale, visual composition and juxtaposing use of actual carpets gives meaning to these works.

Recommended

Form

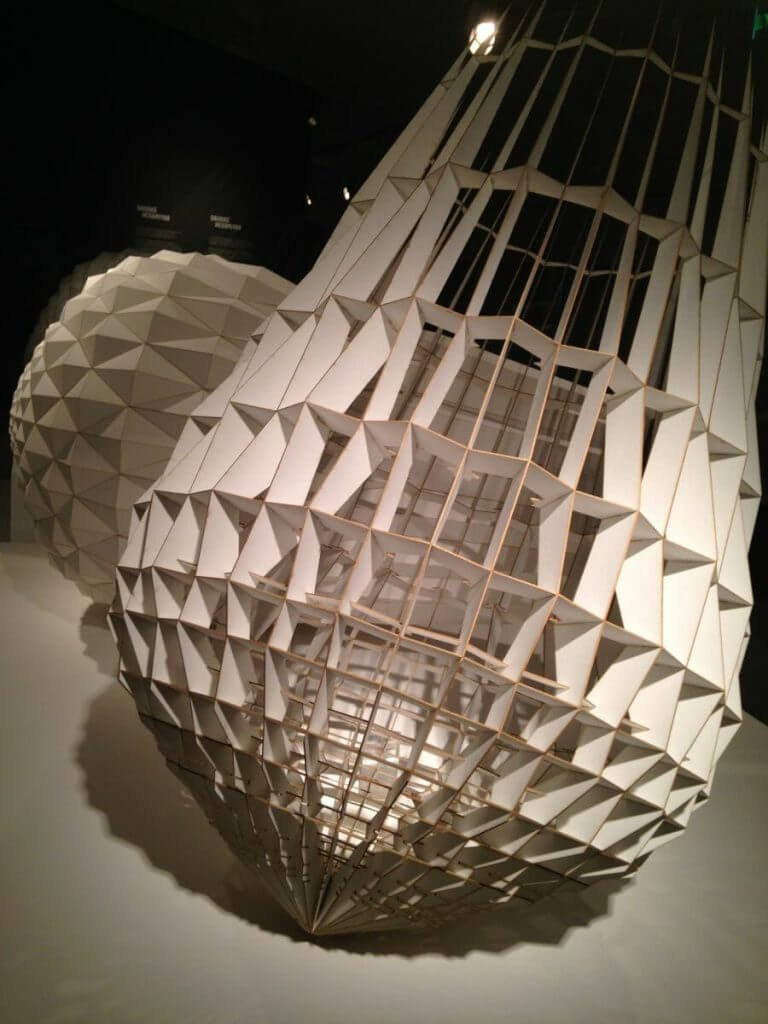

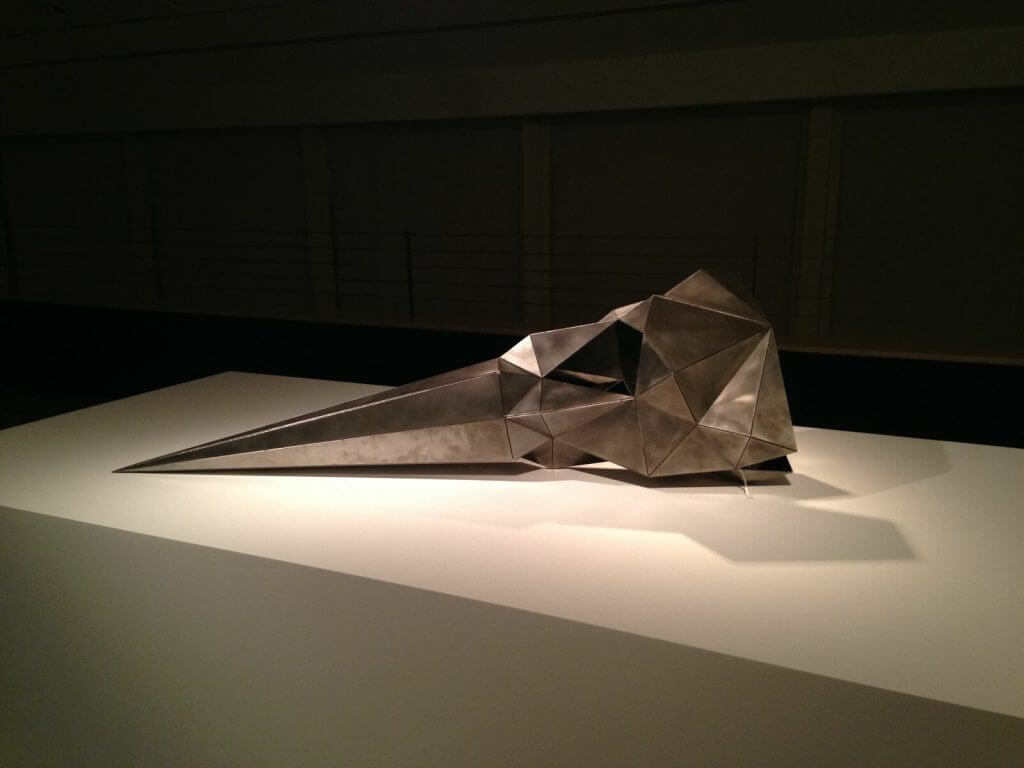

Iranian artist Sahand Hesamiyan creates architectural sculptures out of cardboard and metal. The accessible scale allows the viewer to be drawn into the delicate and pleasing patterns and shadows. The use of materials is also a departure from the source of inspiration- classical ‘rasmibandi’ style vaulting in Persian architecture- with glistening steel and crisp cardboard inducing alterations in our visual perception. The title Khalvat is a poetic reference to mystic solitude and is borne out by this beautiful material struggle in the sculptures.

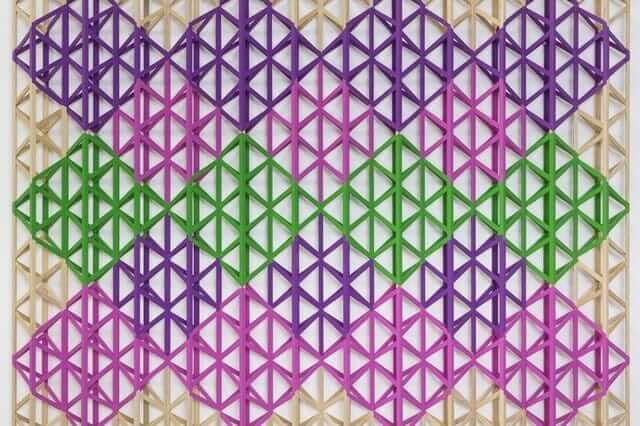

Pakistani-British artist Rasheed Araeen is a veteran who works in painting, sculpture and photography and is known by many for founding the influential journal Third Text. His geometric minimalist abstract sculpture has been a force in the UK for decades; the recent work in this show Spring Come, Happiness Come makes use of more pop-associated color such as pink and purple while alluding to his ongoing theme of the influence of Islamic geometry on Western Modernist Art. Hung like a painting, it is a sculptural work where texture and shadow form a minimalist mosaic.

Space

New York based Iranian artist Shahpour Pouyan uses ceramic techniques to create a series of hat-sized domes based on great architectural ones in both Europe and the Muslim world (see the main article picture at the top). This simple juxtaposition of metaphorical hat/cap/armour with famous domes which ‘express the power of their builders’ creates a tone of both contemplative serenity and increasing uneasiness in the series The Unthinkable Thought. The domes are separated from their ‘bodies’ and are given a new context together on a reduced scale with no apparent utilitarian function (in contrast to the historical ‘object’ in Classical Islamic Art).

Light

Brazilian artist Lucia Koch emphasizes the importance of Islamic artistic influence on Portugal and by extension Brazil. This is a welcome socio-political topic of study (Spain, Sicily and other parts of Latin America could also be included) and the fact that her work has a celebratory element to it makes it stronger. What better way to show the influence than to re-create patterned designs from windows (traditionally used to deflect light and heat) but instead as an interactive installation using contemporary steel and colored acrylic. These screens can be pulled back and forth by the viewer to create innumerable light configurations.

Time

Turkish conceptual artist Cendet Erek uses sound and a minimalist approach to space to express historical events. Ruler Day Night ‘shows the passing of day and night, marked out by the times of the Muslim prayers’ and is noteworthy for its unorthodox and clinical use of a wooden ruler and sound to emphasize time. Ruler 100 Years notes the transition from the Ottoman Empire to the secular Republic of Turkey and the monumental changes from Islamic to Gregorian calendar (1926) and from Arabic to Latin script (1928) in an understated audio-visual work consisting of another ominous wooden ruler.