O

n April 4, 2022, Finnish President Sauli Niinistö and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan held an official meeting. In accordance with the official statement, the two leaders discussed the intricacies of Turkish-Finnish relations, the defense industry, military exports, and the pressing matter of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, which had begun a month prior. The Russia-Ukraine war, in fact, ignited a profound transformation within Finland’s national security and defense policy, prompting considerations regarding potential accession to NATO. Prior to engaging in dialogue with Erdoğan, Niinistö had previously held discussions with NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg, focusing attention on the procedures associated with new and prospective NATO members.

Unraveling the dynamics

A similar shift was also occurring in Finland’s neighboring country and close partner, Sweden. The two nations engaged in discussions with prominent actors such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, and Jens Stoltenberg, expressing their desire for full membership. They were reassured of a warm reception. However, the limitation of consulting only a select few members became evident when journalists queried Erdoğan regarding his stance on Swedish and Finnish membership. Erdoğan, along with a significant portion of Turkey, held an unfavorable view on the matter.

The media was ablaze with theories, circulating in well-established journals and newspapers, attempting to decipher why Turkey was impeding Swedish and Finnish accession: Was Erdoğan maneuvering to gain leverage in the F-35 and F-16 negotiations with the Biden administration? Was Turkey seeking to regain political prominence, or was there a complex plot aimed at assisting Vladimir Putin in managing a crisis?

It is likely that the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Sweden’s reference to the PKK does not solely pertain to the public demonstrations occasionally held by the organization and its supporters in Sweden. Instead, he alludes to the PKK’s extensive network within the country, and describes the PKK’s activities in Sweden as substantial, emphasizing that the funds collected there are utilized by the PKK for terrorist operations against Turkey.

While public protests in support of the PKK serve to illustrate the organization’s presence in Sweden, they pale in comparison to the PKK’s clandestine undertakings. The PKK is deeply intertwined with organized crime, not only in Sweden but throughout Europe. Consequently, Swedish organized crime becomes an inadvertent financier of terrorism in Turkey, while terrorism in Turkey remains one of the central concerns tied to criminal gangs and organized crime in Sweden. However, none of these revelations should come as a surprise to Sweden. Turkey has been raising this issue with its European counterparts for years, only to be met with indifference from all those who have failed to consider terrorism as a relevant problem in any country other than their own.

In a documentary on Sweden’s NATO accession process, which appeared on by the Swedish national public television broadcaster SVT, an interview with former Swedish Minister of Foreign Affairs Ann Linde (2019-2022) was aired, during which she openly acknowledged that while Turkey faced a severe terrorism threat, Sweden and other European countries failed to take the terrorism in Turkey seriously. Linde further affirmed that Turkey’s claims regarding Sweden’s financial support for the PKK were accurate, acknowledging the legitimacy of Turkey’s criticism.

The loss of lives in Turkey has been met with resounding indifference across Europe. On the rare occasions when PKK-related stories capture European headlines, they often portray support for the organization. Many media outlets and policymakers prefer to highlight the PKK’s fight against DAESH and its supposed pursuit of freedom, conveniently overlooking the fact that the organization is recognized as a terrorist group by both the EU and the U.S. Moreover, the PKK is widely acknowledged as an active organized crime network, responsible for a significant portion of drug trafficking throughout Europe.

The permissive stance toward the PKK’s actions has also created problems in France, as a recent case exposed instances of racketeering, blackmail, kidnappings, and extortions carried out by PKK members in southern France.

Sweden’s transformative path

In order to demonstrate its commitment to Turkey and strengthen its approach to counterterrorism and the security of partner nations, Sweden implemented a significant change to its counterterrorism laws. Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson took the extraordinary step of writing an article for the Financial Times to publicize the new legislation. The updated laws now criminalize participation in a terrorist organization and prescribe penalties of up to four years for basic terrorism offenses and two to eight years for more serious offenses. Moreover, leaders of terrorist organizations can face sentences ranging from two years to life imprisonment.

In his article, Kristersson described this development as a means to close a legal loophole in the Swedish system. Previously, being a member of a terrorist organization and supporting such an organization was not explicitly illegal. Prosecution was only possible if the actions of terrorists could be directly linked to a specific terrorist act. As a result, individuals providing logistic, administrative, or financial support to terrorism without direct involvement in a terrorist act itself were not committing a crime; for instance, sending money to a terrorist organization was not illegal unless prosecutors could establish that the funds were used for a specific terrorist act.

Since the implementation of the new anti-terrorism law, Sweden has already charged and convicted one individual on terrorism-financing charges. This person, a Turkish citizen of Kurdish ethnicity, had been in custody since February. He was found guilty of extorting money for the PKK, aggravated blackmail, and related weapons offenses after threatening someone with a gun. The perpetrator also maintained close contact with PKK members in Germany and France, including a senior leader responsible for the PKK’s collection activities in Europe. The Swedish intelligence and counterterrorism service, SÄPO, verified at least 11 instances where the convicted individual was seen moving alongside high-ranking PKK members in Stockholm before visiting restaurants and wholesalers. On July 6, 2023, the Swedish district court convicted the individual on all charges and sentenced him to four-and-a-half years in prison, followed by deportation.

While the issues with Finland were relatively superficial and primarily centered around the ban on defense exports to Turkey, which was even mentioned in the readout of the April 4 phone call between Niinistö and Erdoğan, the challenges with Sweden were of a more substantial nature, necessitating significant changes. Over the past few decades, Sweden has become a safe haven, recruitment hub, financial center, and propaganda base for terrorist organizations operating in Turkey. Swedish ministers have held meetings with PKK members and representatives of the YPG, promising them support.

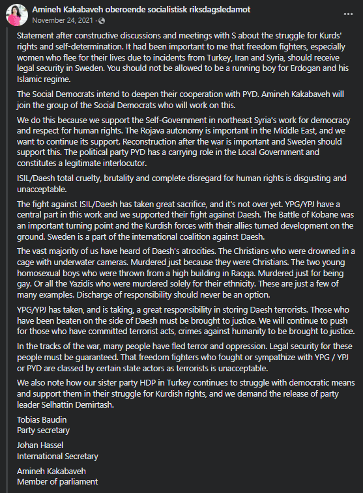

Taking it a step further, the Swedish government at the time relied on the support of independent Member of Parliament Amineh Kakabaveh, a former Iranian Peshmerga member, who extended her support based on the promise of increased assistance to the YPG/PYD, the Syrian branch of the PKK. The details of this agreement were shared in a Facebook post bearing the signatures of Social Democratic Party leader Tobias Baudin and the party’s international secretary, Johan Hassel.

The reason Turkey questions Sweden’s sincerity and commitment to the trilateral Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) lies in a series of events that unfolded during the process in Sweden. Since Sweden announced its intention to join NATO, protests have erupted across the country featuring Abdullah Öcalan and PKK flags. There have been instances of hanging effigies of Turkish President Erdoğan, projecting PKK symbols onto Swedish government buildings, and even the burning of the Quran by far-right activists.

The latter drew widespread condemnation from the Muslim community and escalated the terrorism risk within Sweden. In response, the Swedish police initially banned two further attempts at public Quran burnings, but this decision was later overturned by a Swedish court. The subsequent rejection of the ban was upheld by an appeals court on June 12. Although there have been no Quran burnings in the days following the overturn, it is only a matter of time before such incidents occur again.

Recommended

Tackling terrorism together

Sweden has made notable strides, but has yet to reach the desired level of commitment. Since the change in government, Sweden has undergone a significant shift in its narrative, transitioning from a pro-PKK/YPG stance to one that acknowledges and supports Turkish counterterrorism operations in Syria and Iraq. Part of this shift can be attributed to Sweden’s desire to avoid further offending Turkey, as it still requires Turkish ratification. However, it also appears that the extensive meetings with Turkey and the investigations conducted within the country are gradually leading Sweden to the realization that the PKK and its affiliated organizations are not merely stories of suppressed minorities but rather a complex problem that extends beyond Turkey and has become a concern in Europe as well.

Turkish policymakers are not seeking a temporary change that will end with Sweden joining NATO or with the next Swedish election. They expect a genuine transformation in Sweden’s approach to counterterrorism: Sweden must demonstrate to Turkey that its sincerity and commitment to these changes are enduring.