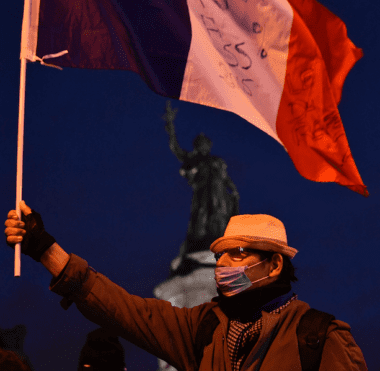

Islamophobia is on the rise everywhere in Europe, and politicians increasingly play with Islamophobic sentiments for political gains. Following the discernibly hostile rhetoric of French President Emmanuel Macron against the Muslim communities in France, Faruk Yaslicimen and Nihan Duran interviewed French sociologist Raphael Liogier, professor at Sciences Po Aix (Institut d’Études Politiques d’Aix-en-Provence) and visiting scholar at Colombia University, on the history and current state of Islamophobia in France.

Q. French President Emmanuel Macron’s recent rhetoric and acts targeting Muslims have aroused a lot of controversy not only in France but also in the global public. Where are we now with the eminent rise of Islamophobia?

Islamophobia emerged in the 20th century in Europe, but the very nature of this Islamophobia has changed over the last decade. It is not a change only in intensity, it is a change in the very nature of what Islamophobia is now. Today, we don’t have Islamophobia, but Islamo-paranoia in France.

Because when you are in a paranoid state, it is very different. You think there is a plot, you presume that there is an intention. The very presumption justifies the action. Because whatever the reaction could be of the Muslim community, we always think that they are constantly at war with us. That is the reason why it would be more accurate to call it Islamo-paranoia rather than Islamophobia.

Q. You talk extensively about the transformation from Islamophobia to Islamo-paranoia. Can you date this back to a certain sequence of events or time? When did it start and how did we get here?

It is a collective paranoia, which is borne out of a narcissistic wound. This means that you think you are losing something narcissistically, you are losing the image of yourself, the image you want to show to others, to the rest of the world.

It is very important for everybody, but it is even more important for Western Europeans because they are used to the idea of being at the center of the world, and this created some kind of a complex; again, I am using the psychological metaphor. And, anti-Islamism, which exists in some parts of the world is directly fed, even constructed, through this complex.

Europe was like the center of the world and what we see throughout the 20th and 21st centuries is the loss of this centrality. The first was the military loss at the beginning of the 20th century.

We [Europeans] lost centrality to the United States of America. But still, until 2003, we had something, we kept our symbolic preeminence, meaning that Europe was still supposed to be the land of human rights, or some kind of moral power.

But in 2003, something incredible happened. The U.S. decided to go to war with Iraq without European powers for the first time. They did not even ask them. And when they talked to them, they talked to them as if they were a colony, not a real ally.

That was the moment when there was some kind of a reversal in the European conscience in general, that created the feeling of being surrounded by enemies. And if you look at it precisely, you can see that all the political parties, which we call the new populist parties were either founded or developed this very year of 2003. All across Europe, these new political parties were anti-Muslim. They all have the same program.

Q. Can you give some examples of these?

The French Front National, for example. It already existed. But from 2003 onward, it changed its ideology completely. Before it was recognized more as an anti-Semite far-right party, but now it turned to an anti-Muslim party. What is more interesting is that this party had an anti-laicity stance before 2003, and after 2003, it became a guardian of laicity, completely the opposite. In the meantime, laicity changed its meaning.

Before 2003, laicity meant the freedom of expression in the public space. Well, laicity stands for that, right? It doesn’t stand to prevent people from expressing their religion; it is to allow people to express their beliefs and opinions.

That is the reason why we have the neutrality. Not at all the neutrality of people, but of the state. However, from 2003 onwards, we changed its interpretation. It was not only the neutrality of the state, but also the neutrality of people, which is very different.

So, we changed completely. In 2004, you can see the act of parliament to prevent the scarf, the simple scarf, in public schools in France. Similar acts reflect the picture all over Europe; and there is something strange with the laicity in France. It is becoming the object of our narcissistic anxiety.

The target is now Muslims. Why? Because Muslims have a peculiar definition in our minds: enemies of the Christian culture, and enemies of modernity and progress.

We are losing something, but we do not know what specifically we are losing and therefore, we need to find a target. And the target is Muslims. Why? Because Muslims have a peculiar definition in our minds: enemies of the Christian culture on the one hand, and enemies of modernity and progress on the other. Thus, you can mobilize masses, both from the right Christian conservative electorates and from the left progressivist electorates.

Q. This is where a deep sense of antagonism in the French society emerges, right?

This is related to the other argument that Muslims see themselves as Muslim first, hence, they value their citizenship less than their Muslim identity. Sometimes on the radio during prime-time shows or in widely read magazines, Muslims are depicted as people who think deep inside that they are Muslims first, and French second.

I remember I watched a film, where they go to a depo in a “secret” place. I myself went to this kind of place with my students and it is no secret. So, in the film, the camera is showing shadowy scenes and there are people with beards, face veils, and headscarves everywhere – quite a scene! And while we watch this on TV, a person in the film says, “If the French law prevents me from practicing my religion, I will not obey.”

Aha! A tremendous scandal against the French republic, and people who are watching immediately react “Look at that! It is awful. If a French law will prevent him from practicing his religion, he will not obey and therefore, he is betraying the republic,” or “He is against the republic.”

Religion is the most intimate thing in our lives, so I find it completely crazy to say “oh, they betray the country” just because they say they choose their faith over a political system. I think it is quite the opposite. And now we are coming to what is happening now.

If one day, the French state, the republic, enacts that people cannot practice their religion freely, and that I cannot practice my religion in the public space, I won’t have any problem with disobeying this law, because it means this state is not a republic anymore.

Due to our imagination of who a Muslim is supposed to be, we are “able” to create a sense of unity. So, we know against whom we can fight. This happened after 2003 in the very structure of the discourses we use.

We presume that Muslims have a plan for France. In such a paranoid state of mind, you’re allowed to do anything to protect yourself. You can react and be violent because whatever you do will always be less violent than what they plan behind closed doors.

Q. This reminds us of the reaction of Emmanuel Macron, following the recent incident, the beheading of a schoolteacher in Northern Paris, who said, “Fear will change sides.” This statement was not only excluding but also threatening to the Muslim community at home. How do you think the everyday racism that the Muslim community is experiencing in France is contributing to the deepening of social divisions in the country?

To tell you the truth, I do not think President Macron believes in what he is doing. I think he is not racist himself, which is even worse, because he does not care. He is not a racist; he just wants to stay in power, and he does not care about anything else. He had a positive discourse before the public, which was negative. But Macron was neither left nor right; he was just talking about a positive agenda. However, he sees that he cannot govern this country with his initial positivity.

So, if people are becoming racists and you cannot fight against this current, you just feed them with what they want. If there were a politician who would fight against this racist populist current by taking the risk of losing the election, he could maybe win the election, and maybe even something bigger than the election. But right now, I do not see anybody like that.

Q. Do you think this is a strategic move for the upcoming election?

I know, because I know Macron’s advisors and I talk to them. I examined his program in detail before he was elected. And it was almost symmetrically the opposite of what he is doing now. He just believes in the economy. And I think he wanted sincerely to change the economy in France step by step. And suddenly an identity crisis has popped up on his way.

Following the terrorist attack in Paris in October 2019, he changed his discourse, because he knows well that waging a tight war against terrorism can give him the chance to unite larger numbers of people behind him.

At first, he did not pay attention to mosques or to the questions of the veil and all that. He left it to the other members of his government. But it seems that his political advisors convinced him that if he wanted to win the election, he could not carry on the way he used to, and thus Macron took the issue at hand. He knows that the majority of the French population is concerned with these issues, so, he tries to anticipate what they would expect from him.

Q. You say that there is a recent change in the discourse and the overall attitude of President Macron regarding the Muslim community in France. How does this resonate with the French public?

The problem is that the French public is completely immersed in this paranoia. There is some kind of a theater, a tragic one. In the scenario, there are different roles and functions for different actors. You have these populists, saying “the real” French people are in danger. These real and good citizens are in danger. And, in front of them, you invent, “the fake” people, the enemy, the Muslims.

You are either a hero or a betrayer. You cannot be both. It is impossible. Macron was about to become a betrayer. Now, he wants to become the hero again.

So, we found the enemy, right? Now, you need to have heroes. Then, journalists as well as politicians have to choose their sides, whether they are with the “real people” or they are with the “fake” ones. So, you are either the hero or the betrayer. You cannot be both. It is impossible. And Macron was about to become a betrayer. Now, he wants to become the hero again, because otherwise, they will think he is with the “enemy.”

And so, to answer your question precisely, what is preoccupying me is not Macron because he is just a politician. He knows, and he is right, that he cannot be elected if he carries on not caring about the collective anxiety of losing French identity, because he will be perceived as a betrayer and will not be elected because the majority of the French people consider themselves as the “real people” in danger by the “fake people.” I am sorry to say that, but that is the case.

Recommended

Q. The division seems so deep. Do you think there is a way to overcome these problems? How can France start to debate this from the right angle?

The first thing we should do is to stop talking all the time about Islam. Because when we comment on Islam, we are discussing Islam per se, and not the Muslim people. But we are just manifesting our own complexes. So, this is the first thing.

Secondly, to ease our socio-psychological tensions, we should stop looking for a reason outside and we need to have public debates to address this very complex issue. We should accept that we are not at the center of the world anymore. We feel weak, but we pretend to be strong externally.

By doing that, we are spending our energy in an extremely useless way and not even addressing the real problems of what is happening here and now. It is pointless. So, what are we scared of? We are scared of our own shadow.

Raphael Liogier is a professor at Sciences Po Aix (Institut d’Études Politiques d’Aix-en-Provence), visiting scholar at Colombia University, and the author of numerous books. Among them are The Myth of Islamization: Essay on a Collective Obsession (2012, Turkish edition is published by Epos in 2012), and The War of Civilization Will Not Take Place: Coexistence and Violence in the XXI Century (2016, Spanish edition, 2017; Arabic edition, 2018). His research focuses on identity, religious identities, collective identities, identity reactions including populism, and how people deal with identity by excluding the identity of others.

VIDEO: Why the Far-Right Is Rising Globally – Emergence (Part I)