T

he Nile River basin is shared by eleven riparian states. The vast portion of the river course originates from Ethiopia’s Blue Nile, or Abbay River, while Egypt and Sudan are the predominant consumers of the Nile River’s waters. As a result, the Nile’s key riparian states are Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan.

After several attempts to deal with integrated basin-wide watercourse management, in 2010, the three states along with the remaining eight riparian states, namely Burundi, D. R. Congo, Eritrea, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda, were able to craft the first-ever inclusive legal regime known as the “Agreement on the Nile River Basin Cooperative Framework” that would lay the ground for establishing a basin-wide commission.

Unfortunately, the states were unable to reach a consensus, however, on the fate of the major colonial treaties, mainly the 1929 Anglo-Egyptian Treaty and its extended 1959 Egypt-Sudan agreement, as Egypt and Sudan insist on their continued enforcement while Ethiopia and other upstream riparian states assert otherwise.

Save the basin-wide deadlocked negotiations on The Nile Basin Cooperative Framework Agreement (CFA) that is awaiting minimum ratification to enter into force, the three riparian states have been in dispute over various issues concerning the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), which is being built on the course of the Abbay River since 2011.

Since the commencement of the construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, the three riparian states have held on-and-off talks regarding the references that would create a conducive environment for their roundtable negotiation over the dam. Accordingly, despite the intermittent nature of the talks, the decade-long negotiations have borne fruit in establishing various technical committees, such as the International Panel of Experts (IPoE) in 2012 and the National Independent Scientific Research Group (NISRG) in 2018. The negotiations also brokered the “Declaration of Principles on the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam” in 2015, which is applauded for laying a fertile ground for the forthcoming negotiations, especially, for talks over the dam’s first filling and operation.

With the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam as a corner stone, the three riparian states have agreed to be bound to, inter alia, the principles of cooperation, development, no significant harm rule, and equitable and reasonable use per Article I, II, III & IV of the “Declaration of Principles,” respectively. Furthermore, Article V dictates that the three riparian states respect and act as per the outcomes and recommendations of the technical committee. Although the three states have endorsed the IPoE’s final report, they could not agree to do the same for the studies of the other technical committees. Especially, the NISRG, which was tasked with providing alternative procedures on the first filling and operation of the GERD, made promising progress; however, it failed to come to terms with the baseline scenarios, which dragged them toward the colonial agreements.

Colonial history, the Nile, and the GERD

The colonial accords, notably the 1929 Anglo-Egyptian Treaty and 1959 Egypt-Sudan agreements, allocate the bulk of the Nile River flow exclusively to the two downstream riparian states, namely Egypt and Sudan. Considering these one-sided arrangements as baseline scenarios for the first filling and operation of the GERD ultimately led to affirming the colonial treaty regime, which Ethiopia firmly stands against. Added to this, while Ethiopia plans to fill up the dam in 4-7 years, Egypt insists that this should be done in 7-10 years. For these and other contributing factors, the three riparian states could not reach a compromise and the negotiation reached a deadlock.

Upon Egypt’s call on the international community to intervene, negotiations led by Washington began in November 2019. However, the three states failed to agree on the drought and flood mitigation plan, which puts a heavy burden on Ethiopia, and the dispute resolution mechanism, which calls for binding arbitration. Moreover, although Ethiopia was pressured by the United States to sign a draft agreement, it refused to do so and pulled out of the negotiations.

After the negotiations failed, in June 2020, the African Union (AU) took over the GERD matter and negotiations began to take place under the aegis of the AU chairperson with no breakthrough as of yet.

The African Union and the GERD

Even though the trilateral and/or AU-led negotiations have not been exhaustively utilized, Egypt internationalized the issue and requested the intervention of the UN Security Council. Ethiopia objected to the request stating that the GERD is a regional matter, which procedurally should either be resolved through tripartite negotiation or be dealt with under the auspices of the AU. The UN Security Council backed down and dictated that the three countries come together and solve their differences amicably.

For the last couple of years, negotiation over the GERD has been put on hold due to the conflict in Ethiopia and political instability in Sudan. Although the three riparian states have not issued an official communiqué, there are reports indicating several confidential negotiations have taken place in the United Arab Emirates, but with no significant progress.

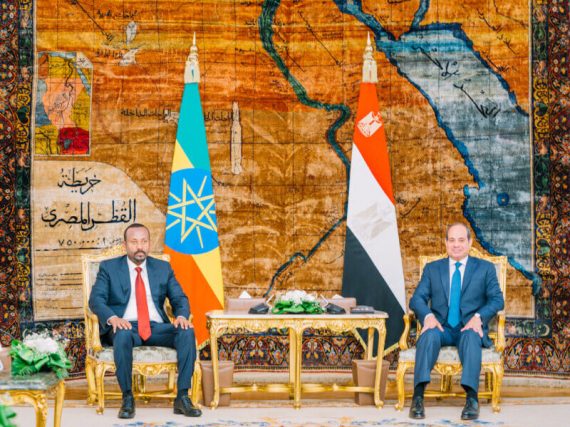

Recently, after Ethiopia’s prime minister vowed to delay the fourth filing of the dam until September 2023, a joint statement was issued following a meeting with the Egyptian president in Cairo in early-July 2023. It was agreed to re-initiate tripartite negotiation over the GERD and a pledge was given to conclude negotiations in four months. Despite the unrealistic ambition of the statement given the track record of the last ten years, the statement shows the ambition, willingness, and commitment of the riparian states to solve the sticking issues quickly. The move is a big step and could be a huge relief if the three states pursue the negotiation in good faith, compromise their interests, and come to agreeable terms in a win-win manner.

Currently, more than a month after the joint statement, it was not clear yet where and when these negotiations were going to take place, until it was made public that the negotiations commenced on August 27, 2023 in Cairo, Egypt. Moreover, recalling the ongoing war in Sudan, it is naïve to assume Sudan is going to engage proactively in tripartite negotiations. What is more, the joint statement was issued by two riparian states, and primarily Ethiopia. Thus, the talks are practically going to be bilateral, notably between Ethiopia and Egypt.

As the move impliedly ignores Sudan, it raises trust issues. Reports have already started indicating that Sudan is dismayed by the move. Although Ethiopia and Egypt are the two major riparian states, Sudan’s concerns should not be ignored given its geographical location midstream, and its role and significance in the tripartite negotiations.

There is little doubt that states are free to negotiate openly or secretly whenever and/or wherever they want in the presence or absence of a third party. The three riparian states might openly or secretly pursue their negotiations either in their respective state/city, under the auspices of the AU, in a third country like the U.S. or UAE or agree otherwise and negotiate accordingly. What matters the most is whenever and wherever talks are going on, it has to be pursued in a good faith whereby their respective national interests, tripartite negotiations, and basin-wide cooperation are prioritized in a balanced manner.

Recommended

Against the above context, before the actual commencement date was made public, there was an assumption that negotiations might have already confidentially begun in the UAE given the experience of the last two years. Recalling the two downstream riparian states’ mechanisms to pressure Ethiopia, and the Arab League’s position on the GERD, there could be scenarios in which the UAE, using its economic leverage, might pressure Ethiopia to sign a binding deal. Had the assumption been true although the UAE, like the Washington-led negotiations, is not expected to pursue an active role in the negotiation process, it would be unwise to rule out such a possibility.

Now that the whereabouts of the negotiations over the GERD are public, the riparian states need to pursue their talks in a way that would address the remaining unresolved issues on the filling and operation of the grand dam. Most importantly, they should consciously pursue their negotiations in such a way that would not affect future basin-wide negotiations over the equitable and reasonable use, and the fair share of the entire Nile River course among all riparian states.

Furthermore, in the past, the AU has sponsored the GERD matter and has not issued a communiqué indicating any new developments. Thus, the righteous approach would be to continue negotiating under the AU. The riparian states need to pursue the dogma of “African solutions to African problems,” retain the GERD matter under the AU, and transparently walk the talk under its chairmanship.