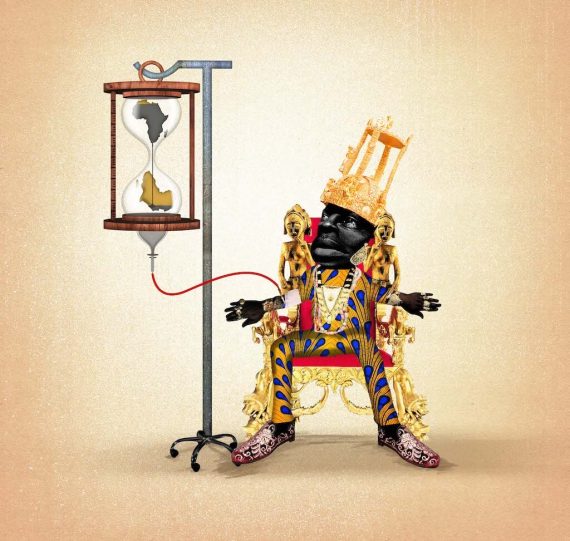

Among the many afflictions that Africans must endure today, the most dangerous might be their leaders’ growing enthusiasm for geopolitics. Across the continent, politicians are convinced the time is ripe for African nations to become more influential and autonomous actors in world affairs. In this context, the metaphor of Island Africa acquires a double meaning—the continent is both distinct and central at the same time, able to assert a unique identity while claiming a greater share of power in global networks that need its resources and consent more than ever.

In the past, great powers exploited Africans as colonies and pawns, but now the tables have turned—China and Russia are undermining American and European dominance—and African leaders look forward to playing a new version of the great game, this time in a starring role.

This self-confidence may surprise observers accustomed to seeing Africa as a sphere of influence constantly vulnerable to outsiders competing to carve out special zones and dependent client states. Indeed, America’s diplomats and generals still imagine Africa as remaining in exactly this sort of passive posture. Inside the Beltway, the prevailing view is that Chinese companies and Russian mercenaries are creating mischief, exploiting Africa’s weaknesses for their own gains while sabotaging Western efforts to strengthen local militaries against growing threats of cross-border terrorism and insurgency.

With increasing alarm, Washington warns African leaders to beware of debt traps and arms races that threaten peace and democracy. Reject Chinese telecom investment, limit Russian military training, don’t turn your backs on Western friends who’ve provided the arms and finance that kept you afloat for so many years.

African leaders have grown accustomed to these admonitions and they’ve learned to use them to good advantage in playing off outside powers against one another. Having multiple options strengthens the leverage of African negotiators in many fields—trade, resource extraction, arms deals, human rights disputes, technology transfer, diplomatic standing, aid packages, loans, investments, and more.

At the same time that African rulers are juggling foreign relations, they are also trying to sort out power relations among themselves. If Africans are going to rule Africa, then which countries will lead and which will follow? If the dream of pan-African unity is as elusive as ever, then what practical steps can encourage greater integration? If the continent is too vast to be governed as a whole, then how many Africas should there be?

For the largest and strongest African countries, the slogan of regionalization has become the favored response to these questions about inter-African power.

For the largest and strongest African countries, the slogan of regionalization has become the favored response to these questions about inter-African power. The basic approach assumes a broad consensus over the historic existence of distinct regions shaped by topography, ecology, climate, migration, culture, language, state formation, trade networks, and links to other continents. The number of regions is open to debate, but usually limited to five or six. Supposedly, each region has a particular political dynamic—an implicit hierarchy of power with one or two preeminent states standing above their neighbors.

The promise of regionalization is to create benevolent hegemons in each zone—top dogs that will promote the interests of their neighbors instead of exploiting them. In theory, this handful of local hegemons would create a continent-wide balance of power system that would promote peaceful competition and development to the benefit of all Africans. Regional institutions would have the authority to negotiate with non-African states, channeling aid and investment to agreed sectors and locations. They would also provide collective security and defense bolstered by formal processes of representation and deliberation.

The implicit aim of regionalization is to legitimize hegemony by cloaking it in the rhetoric of balance of power stability. These are the moves of weak governments whose greatest threats are not from neo-colonialist foreigners but from their neighbors and their own citizens. Unable to rest their legitimacy on real consent, they hope to create an illusion of popular support by fulfilling the manifest destiny of transnational regions and, ultimately, of the entire continent. By enshrining hierarchy and sidestepping civil society, the would-be hegemons are likely to spark exactly the wars and revolutions they dread and claim to be preventing.

Regionalization is a formula for bringing the great game home, making the struggle for power an African affair disguised as greater integration, development, and global influence. National borders are supposedly inviolable, but sovereignty must be pooled to overcome debilitating fragmentation. Consensus is valued, but decision making should be concentrated in fewer hands and more expert circles. Multiple hegemons presumably respect one another’s right to coexist, but ranking and subordinating are inherent aspects of trying to balance unequal partners. In this way, balancing becomes a pretense for narrowing hegemonic elites and winnowing their number over time.

Recommended

This approach to centralizing power—as opposed to legitimate authority—invites resistance and bloodshed from many directions at once. If Africans have been so determined to expel foreign oppressors, why should they now rally behind home-grown princes with similar predatory instincts? In an era of global civil society and transnational rebellion, why would African citizens resign themselves to watching local elites command a global playing field while they remain on the sidelines? In fact, the more popular sentiment in Africa favors greater devolution of power and local autonomy—precisely the opposite of regionalization’s path toward hegemonic consolidation.

Outside powers might endorse these developments for several reasons. They could concentrate on their higher priority struggles with one another while leaving Africa to its own devices. The greatest costs of government and security would be borne by African elites without constant and direct engagement from foreign patrons. Foreigners could maintain their distance while competing more vigorously—though not more safely—for commercial and diplomatic advantage.

Great powers—despite their divergent interests—are buying into the African discourse on regionalization without appreciating its inherent flaws and self-defeating tendencies.

And, with so many rivalries between states and opposition movements, opportunistic foreigners would have wide room for troublemaking if they chose to weigh in, openly or covertly. Prime examples include the competition between Nigeria and South Africa for unofficial leadership of pan-Africanism, the confrontation of Egypt and Ethiopia over control of the Nile River Valley, and long-simmering tensions pitting Algeria against Morocco in North Africa and Kenya against Tanzania in East Africa. Following this logic, great powers—despite their divergent interests—are buying into the African discourse on regionalization without appreciating its inherent flaws and self-defeating tendencies.

VIDEO: Mercenaries Reborn: How Private Armies Violate Human Rights

Many debates over African politics mirror questions about the changing character of the international system in general. In a post-American world, what is the optimal number of rivals for a multipolar balance of power? Can stable alliances or concerts of powers substitute for absent hegemons? Can new hierarchies form under rising powers willing to provide public goods to an international society that is both more interconnected and more fragile?

Sadly, the African and global discussions often underestimate the importance of legitimacy and its unavoidable reliance on popular consent and wider participation. At both levels, governing elites are so preoccupied with clinging to power that they neglect mounting worldwide demands for greater power sharing—among nations, classes, and generations.

In Africa and beyond, power sharing is fleeting, and power grabs are endless. Entrenched elites pour more energy into refurnishing their penthouses even as the lower floors and foundations are crumbling beneath them. But no system of hierarchies and hegemons is salvageable. Circulating elites and fine tuning their pecking orders are certain recipes for failure—unless we become so discouraged as to conclude that war and revolution are the only remedies left for unjust institutions incapable of reform and self-correction.