The dream of natural gas bonanza in the Eastern Mediterranean naturally boosted littoral states’ expectations of economic benefit from ownership, exploration, exploitation, and transportation of natural gas reserves discovered in the region. Accordingly the international community – at the beginning – hoped that exportation of Israeli gas to Europe (possibly via a sub-sea pipeline to Turkey) could advance cooperation among regional states, make a political solution easy for already existing disputes like the Cyprus Question, and strengthen interdependence between Europe and the region.

These positive expectations led the Obama Administration to believe that the interested parties, which were potential stakeholders as buyers and sellers of natural gas as well as beneficiaries of energy firms, could be convinced to invest in a new Mediterranean cooperation. However, after 2011, neither did the USA show its willingness to support regional economic cooperation on the Eastern Mediterranean gas basin, nor did they support the newly found gas reserves by Israel. The Greek Cypriot Administration (GCA) and Egypt led the reinvigoration of an inclusive gas partnership. Geopolitical conditions radically changed after the Arab Spring and stakeholders of Eastern Mediterranean gas basins adopted competitive agendas in the ongoing conflicts. Since then geopolitical rivalry, not economic rationality, has become the main determinant of the limits of Eastern Mediterranean energy cooperation.

This competitive geopolitical atmosphere was first used by the GCA to violate the legitimate rights of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC). On one hand, the GCA signed so-called EEZ agreements with Israel, Egypt, and Libya without taking the consent of the TRNC therefore, ignoring the economic, political, and legal rights of Turkish Cypriots, and also unilaterally dividing its so-called EEZ into blocks and inviting energy companies like ENI and Total to explore and drill offshore reserves around Cyprus. This is a violation against a part of Turkey’s continental shelf in so-called blocks 1,4,5,6, and 7. On the other hand, Tel Aviv exploited geopolitical faultlines in the region to marginalize the rights of Lebanon, Syria, Turkey, and TRNC in the maritime zones of the Eastern Mediterranean and to exclude them from the institutionalized attempt of regional energy cooperation (the East Mediterranean Gas Forum).

Likewise, the U.S. took advantage of geopolitical polarization in the region to constrain Russian maneuvering space after 2015 and to pressure Iran by restraining the Syrian Regime and Lebanon after 2017. Hence, western actors supported trilateral energy partnership attempts, on the one hand between Israel, the GCA, and Greece (East-Med partnership); on the other hand, between Israel, the GCA, and Egypt. By backing these opportunist realignments, they encouraged an atmosphere of rivalry instead of inclusive and viable energy cooperation.

Energy firms are reminding us of the economic rationale behind the drillings

Within this framework of geopolitical rivalry, the economic side of the story, the expectation of benefits as well as the feasibility of the cost of investing in East-Mediterranean natural gas dreams, are forgotten. As is known until now, the projects excluding Turkey and the TRNC from the energy deals have not produced any tangible economic results. Therefore it is not wrong to assume that East-Med-like projects have turned out to be an illusion that was shattered recently when energy companies like Exxon-Mobile, ENI, and Total stopped their drilling operations in blocks 6 and 10 and postponed them till March/April 2021 because of the current energy landscape.

The most remarkable feature of the current energy outlook is falling oil prices. At the time of writing, the Brent crude is 42.30 USD which is not enough to motivate key energy companies to take high financial burdens and even higher political risks of investing in East-Med partners’ pipeline dreams. As one can remember oil prices began dropping in January because of the fall of demand to hydrocarbons in Asian markets affected by the coronavirus outbreak. Before European markets were hit by Covid-19, a price war begun between Russia and Saudi Arabia. The USA, feeling the negative impact of dropping oil prices on its national oil industry, had to pressure Riyadh to reach a deal with Moscow on production cuts. Since then oil prices have gradually risen. However, this sign of improvement is not expected to change market conditions in the Eastern Mediterranean energy game because of two reasons:

Recommended

The first reason is related to the current hydrocarbon surplus in the energy markets. Even before the coronavirus crisis there was more supply than demand for oil and gas and Covid-19 is just amplifying this problem. The Asianization of energy markets (reversing the route of East-West energy trade) has been proposed as a remedy but there is no such aspect of Asianization in trilateral Eastern Mediterranean energy partnership plans yet. Indeed, energy experts from the stake-holding firms, like ENI, have already announced their doubts about the economic and technical feasibility of the East-Med pipeline (1200 km off-shore, 500 km onshore length connecting Greece to Italy as well as 1550 km off-shore, 20 km on-shore pipeline connecting Greece to Bulgaria).

Moreover, some actors like France that are eager to take part in East Mediterranean geopolitics by providing security support to stakeholders in dealing with risks against critical infrastructure, are faced with the problem of maritime sustainability when the Covid-19 pandemic hit their naval deployments in the region. Hence security costs associated with the longest and expensive East-Med pipeline project become more apparent under the coronavirus pandemic. Therefore, it can be expected that international energy companies will lose their incentives to continue drilling activities in the Mediterranean. While energy companies are postponing drilling operations, Greek Cypriot and Egyptian authorities keep talking about the expansion of natural gas production from the East Mediterranean reserves. Thinking about the capabilities of planned pipelines like East-Med, expanding national gas production can be counterproductive even if it will be realized. Besides, WHO voiced the possibility of a second wave of Covid-19 which may further restrain global hydrocarbon demand.

On the eve of a new geo-economic era

The second reason is about Turkey’s capacity and determination to counterbalance any geopolitical design marginalizing the role and interests of Turkey and TRNC in the region. One of the key strategic moves in this regard was the signature and ratification of the Delimitation Agreement of Maritime Jurisdiction Zones between Turkey and the UN-recognized Government of National Accord (GNA) of Libya. By this agreement, the realization of the East-Med pipeline on the planned route (Israel- the GCA-Crete/Greece) will be impossible.

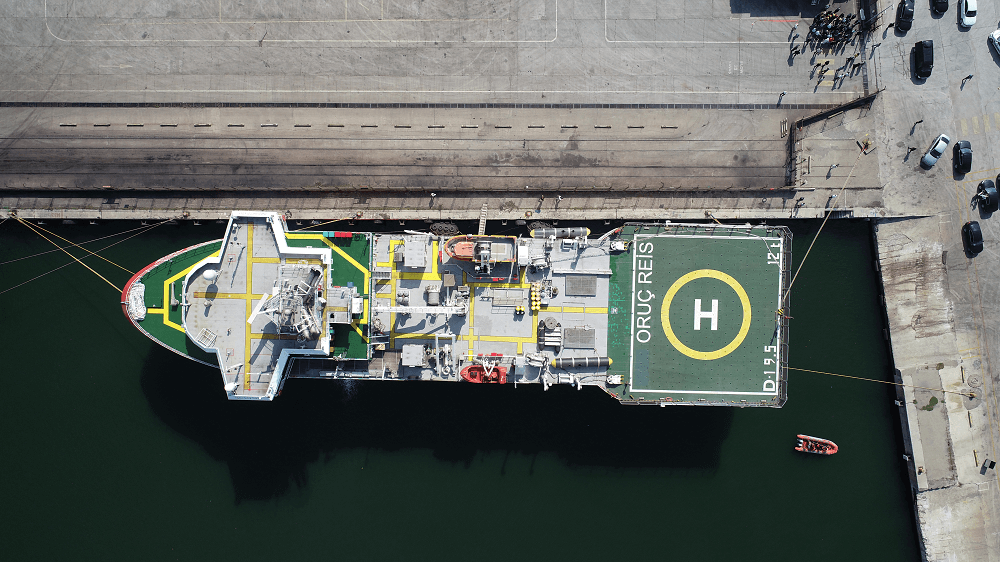

Further insistence on the East-Med will complicate the continental shelf dispute between Greece and Turkey and “being a party of a complex political dispute is not among the objectives of an energy company” as is stated by one of the ENI experts. Besides, Ankara’s continuing drilling operations via Fatih and Yavuz – national offshore drilling vessels – in Turkey’s continental shelf and TRNC’s maritime zones as well as Turkey’s offshore naval sustainability during the Covid-19 crisis, proves that Ankara can exert operational power even in a time of crisis.

Recent news about TPOA’s search for new oil and gas exploration permits in the region reveals that new energy negotiation tables to discuss more viable, feasible, and inclusive energy exploration and transportation alternatives may emerge in the future. Ankara has already stated that she is ready for sincere dialogue with the littoral states in this regard. And now some key players like Italy, which does not want to stay outside of these new plans, express their readiness to cooperate.