Accommodation or the right to adequate housing, as a human right, is an integral part of the right to an adequate standard of living. However, the world has lately been dealing with an unprecedented surge in housing and rental prices that threatens this very fundamental right. Realtor companies, research centers, the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey (CBRT), and the Turkish Statistical Institute (TSI) data provide enough evidence that house prices and rental costs are soaring, up to a few hundred percentage points in Turkey.

This recent sizable jump in property prices and rental rates, however, is mainly due to supply shortage and increasing costs of production. There is, overall, certainly a very high demand due to the younger population, increasing external demand, and recent migration waves towards Turkey. Meanwhile, housing supply has also been relatively weak and insufficient, which has affected the increasing house and rental prices and often leading to false allegations against immigrants.

Meanwhile, as of June 2022, official records reveal that the average housing demand from foreigners is about 5-6 percent of the total demand in Turkey. In other words, foreigners, and especially immigrants, are being scapegoated and hence, there is an urgent need to shed light on some misperceptions over property prices in Turkey and put an end to the theory that mainly immigrants or foreigners cause inflation or house price booms.

Housing and rental costs

Inflation is making life very costly for everyone living in Turkey, just as it is globally. Inflation rate has recently hit 79 percent—the highest in the past 24 years. Residential property prices and rental rates are among the leading factors in this figure. Decreasing supply in the past few years (especially during the pandemic), policies that surge demand in Turkey, increasing costs of production (a negative supply shock), and increasing demand are considered amongst the primary reasons for this surge.

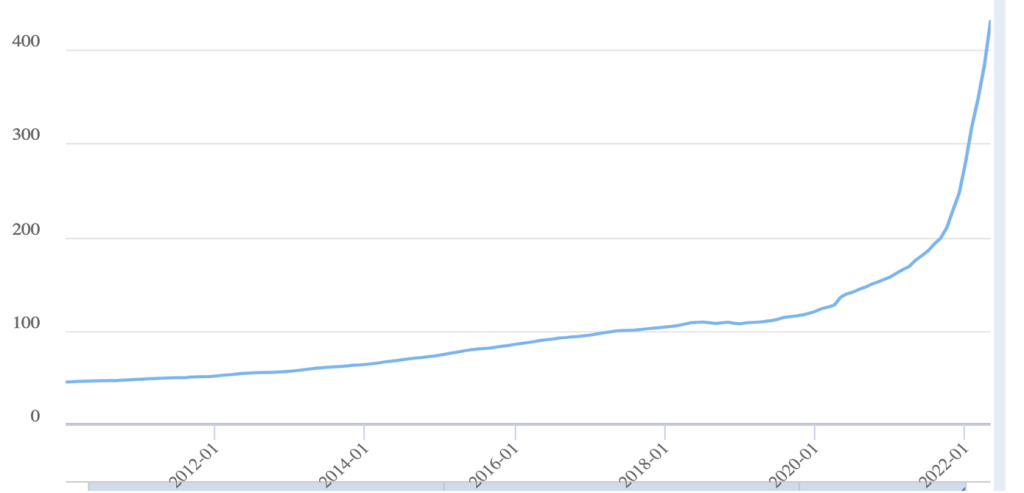

Figure 1: The CBRT Residential Property Price Index in Turkey, Source: CBRT

The CBRT Residential Property Price Index (RPPI), for example, has reached 430.60 in May 2022 (Fig. 1). In 2017, this figure stood at 100. As of May 2020, the annual RPPI inflation is at 145.5 percent YOY (year-over-year). The inflation adjusted real-terms growth in residential property prices, on the other hand, is at 41.1 percent YOY. The real-terms growth in particular, is pretty much in line with the respective figures in the U.S. and Europe.

Rental rates are no different. Rental prices are up by 300-400 percent in some regions in southern Turkey, and up by 200-300 percent in some neighborhoods in Istanbul. Data by Endeksa, a private realtor, shows that, as of June 2022, rental rates in Muğla, a southwestern tourism hub, are up by 73 percent (reaching15,000 TL); in Antalya by 310 percent (10,400 TL); and in Istanbul the average rental rate is up by 168 percent (8,100 TL).

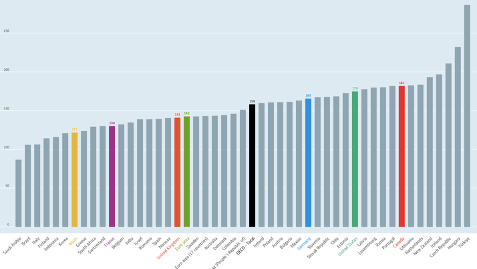

Of course, just as with the ongoing global inflation problem, soaring property prices and rental rates are also a global issue today. The U.S., the UK, many European, or even Asian economies such as China are facing new rounds of property crises and unprecedented price hikes in different forms. As Figure 2 demonstrates, many European and North American economies are facing this run-up in property prices. Turkey, with its relatively higher internal and external (exchange rate) inflation, is an outlier nowadays, and has a relatively higher price surge.

Figure 2: Nominal house prices, index is at 100 in 2015, data till Q2 of 2022. Source: OECD

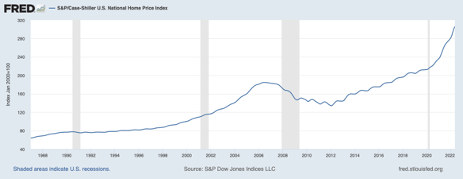

In the U.S., the Case-Shiller Home Index reached 306 in May 2022. In January 2022, the index level was at 212, which means there is a 44 percent increase in the valuation of an average U.S. house over the past two and half years (Fig. 3). Average house prices are up by 10-15 percent in the past year, according to the National Association of Realtors (NAR). In the UK, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) data shows it would, on average, take a paid employee around 40 years to save and invest in order to buy a house.

Figure 3: Case-Shiller Home Index in the United States. Source: St. Louis Fed FRED database

Property bubble arguments, rocket high rents around the world are evident. However, recent tightening cycle and its further consequences for the global property markets are yet to be observed. The increasing costs of production, the rising cost of debt due to the recent tightening trend, and the concerns that properties are overpriced need to be kept under careful scrutiny. So, what can we expect in the future?

Commercial property investments are lately in decline in the West, including in the U.S., the UK, and Germany. China is already shaken by the property crisis or the Evergrande crisis in particular, and homebuyers are refusing to pay mortgage loans. The post-pandemic demand for rural areas and land may also take down urban real estate prices.

New trends such as remote work may also help bring down demand for office rentals. Swiss bank UBS expects a 20 percent decline in demand for office leases. Shares of real estate companies and real estate trusts may also go down, but house prices are likely to remain high—hopefully, however, without increasing further.

Why does the property market matter?

The property market, or housing market, is good source of foreign exchange (FX) revenue for countries such as Turkey. It is a supplementary source of FX reserves to sectors such as tourism, export, or borrowing. Especially in these days of harsh FX reserves debates and the tightening cycle, FX revenues from property markets make a significant difference.

The relatively immense demand due to the young population, external demand, and recent migration waves (from Ukraine-Russia, Syria, and East Asia) juxtaposed to the weak and insufficient supply have led to a demand surplus that puts an upward pressure on house prices. Increasing production costs further increase prices everywhere around the world, including Turkey. For example, in Turkey, the rate of change in cost of property production is over 106 percent YOY according to the TSI.

The property market is also a new safe option for financial investment, given the high inflation figures and the lack of investment options protecting against high inflation in countries like Turkey. Just as the commodity gold, property is a traditional investment instrument for a Turkish family. After all, financial deepening is also relatively weak. Even funds have recently been directing their financial capital towards properties around the world. In the past year alone, property prices are up by almost $1 trillion.

Housing and real estate markets are, in the meantime, amongst the Turkish economy’s critical real-growth economic sectors. They have a roughly 5 percent share in the GDP, but are a crucial source of the economy’s propagating mechanism and a good employment option for many low-skilled employees, including immigrants.

Immigration and the house of inflation

The growing number of immigrants and refugees contribute to the domestic demand and add up to the inflation figures mostly through housing and food, but most importantly over the expectations looking forward. The presence of immigrants and refugees is considered one of the drivers of high inflation in Turkey and the U.S. (as opposed to energy and food-based inflation figures in Europe). High demand and house prices are also considered as part of measures to deal with high inflation figures in Turkey.

The high population concentration in certain neighborhoods is definitely not good, as it can drive up prices. For example, about 800 neighborhoods in 54 cities in Turkey are already shut to further foreign residents, as foreign residents already constituted 25 percent of the population. Recently, this rule was changed again and Turkey started limiting residence permits for foreigners where they exceed 20 percent of the population in certain neighborhoods. The number of listed neighborhoods went up to 1,200 as of July 1.

This new measure will help facilitate the potential positive outcomes of the recent migration and immigration waves. For instance, it will help deal with increasing housing prices in certain cities or neighborhoods in Turkey, and potentially move new applications to other cities or neighborhoods outside the city centers. This will help deal with the huge demand concentration in particular areas.

This measure will also help deal with the anti-immigrant sentiment, which recently is more often provoked in Turkey. These types of new arrangements will remove a major political argument from the hands of the opposition party leaders. The rule also adds to the earlier plans to return one million Syrians with temporary protected status (TPS) to Turkish-controlled northern Syria.

Recommended

The total number of foreigners and immigrants in Turkey stands at 5.5 million, according to the Presidency of Migration Management. This figure includes Syrians with TPSs and makes Turkey a leading immigrant-hosting country. However, along with very high inflation and housing price surges, the anti-immigrant sentiment has also risen. In particular, immigrants are being scapegoated for all the price surges and unemployment in the country.

The Turkish inflation and recent surging property prices are predominantly due to the supply shocks, and cost-related external factors such as energy prices, broken supply chains, and food prices, as well as expansionary policies that raised demand for property and the exchange rate movements, which has less to do with foreigners, be they immigrants or refugees.

Immigrants, on the other hand, have a much-limited share in demand and the resulting house of inflation. They rather provide the much-needed labor supply in many low-skill industries that regular Turks would sniff at. They provide labor cost advantage for Turkish manufacturers. Contrary to the common belief, immigrants and refugees should be considered as a good source of the much needed labor supply and human capital.