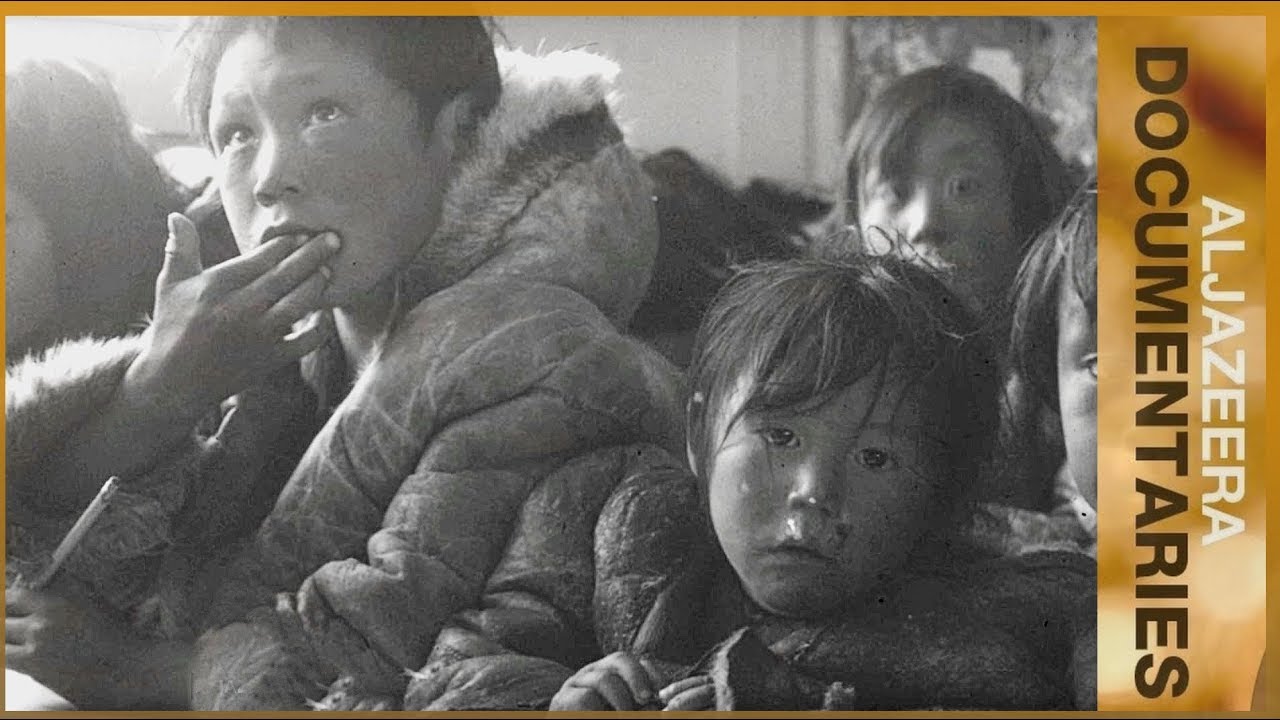

Over the months of May and June 2021, hundreds of unmarked graves of Indigenous children have been exposed in Kamloops, Brandon, Marieval, and Cranbrook across what is today called Canada. Many more are sure to be exposed in the coming months. All of them were near the former sites of Canadian “Indian Residential Schools,” which were fundamentally institutions of forced assimilation and genocide, more appropriately called prisons than “schools.”

I want to emphasize the word “exposed” here because none of these stories of children murdered by Canada’s structural violences, abandoned and disposed in unmarked graves, are new to Indigenous people. They have known, lived, and survived these stories for decades. The Canadian state itself also knew about these stories but has been for years actively trying to conceal the horrific crimes it has committed. This story is only “new and shocking” to a Canadian and international public that has bought into Canada’s projected self-image of an enlightened and progressive state and society.

Canada promotes itself on the world stage as a progressive model of “liberal democracy” in which ideals of “reconciliation,” “tolerance,” “multiculturalism,” “justice,” and “truth-seeking” flourish within its state structures. This diplomatic image is misleading though, and Canada’s crimes against Indigenous Peoples are only properly understood, not when they are posited as “dark chapters” or “historical mistakes,” but when they are situated within the historical and ongoing context of the imposition of a genocidal settler colonial sovereignty.

In today’s political discourse, the term sovereignty has become associated with the modern nation-state, where a central sovereign political body practices, at least in theory, supreme authority over a specified land and people. This is especially the case in settler colonial contexts like Canada, where Indigenous people are largely viewed as another minority group that must be assimilated into the supreme sovereignty of the Canadian state, as opposed to what they in fact are: sovereign original Peoples.

Throughout their long history and until today, Indigenous Peoples from First Nations, Inuit, and Métis have developed complex societies with complex systems of social and political organization

Sovereignty did not always follow this Euro-American colonial meaning or practice. Throughout their long history and until today, Indigenous Peoples from First Nations, Inuit, and Métis have developed complex societies with complex systems of social and political organization. Within these rich traditions and societies, multiple forms of sovereignty were imagined, theorized, and practiced.

It is impossible to fully explain what Indigenous sovereignty means in a short piece. But what we can say is that Indigenous sovereignty that flourished prior to colonization and still survives today in the values, praxis, and indeed existence of Indigenous people, is generally layered and shared.

As we learn from the writings of Indigenous scholars like Audra Simpson, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, and Glen Coulthard, decolonial Indigenous sovereignty gleans its authority from living with the land and in openness towards difference and the plurality of people. It asserts a communal type of freedom and a responsibility to each other and to the land. Whereas the settler colonial state sees the self-determination of the nation as exclusive to an imagined homogenized and purified racial identity, Indigenous sovereignty in its foundation is open and attentive to difference, plurality, and sharing.

Canada never tires of projecting a plural and multicultural self-image to the world, painting itself as a state of civic nationalism, where ethnic and racial identity does not determine citizenship status. This is of course a highly dubious claim when we examine Canada’s racist policies against Black and Muslim people for instance, but even if we grant that civic nationalism is the aspiration of the Canadian state, it is critical to underscore that Canada’s foundations are ethno-national and remain so until today.

Foundationally speaking, Canada is an ethnonational state because it refuses to acknowledge the political rights of Indigenous Peoples as sovereign Nations, and asserts instead exclusive sovereign authority for what it imagines as the British and French “founding nations” of Canada.

Under the veneer of Canada’s image as a multicultural liberal democracy is the ongoing operation of structural settler colonial violences.

In short, under the veneer of Canada’s image as a multicultural liberal democracy is the ongoing operation of structural settler colonial violences, which eliminate Indigenous people and sovereignty and replace them with settler colonists and exclusive European settler colonial sovereignty.

Where is Canada’s truth and reconciliation?

Responding to the Chinese government’s call for the United Nations to investigate Canadian crimes against Indigenous Peoples, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau had this to say:

“The journey of reconciliation is a long one, but it is a journey we are on. China is not recognizing even that there is a problem. That is a pretty fundamental difference. In Canada, we had a Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Where is China’s truth and reconciliation commission? Where is their truth? Where is the openness that Canada has always shown and the responsibility that Canada has taken for the terrible mistakes of the past, and indeed, many of which continue into the present?”

Trudeau is referring here to China’s “systemic abuse and human rights violations against the Uyghurs.”

It is of course highly doubtful that the Chinese government is genuinely concerned about the well-being of Indigenous Peoples, any more than the Canadian government is genuinely concerned about the well-being of the Uyghurs. It seems to me that both are using each other’s state violences as a means through which they can advance their own state strategic interests.

Putting that aside, and more to the point, is Canada really interested in the truth? And has it taken serious responsibility for its ongoing structural settler colonial violences? The answer for both is clearly, no.

Recommended

First, it is important to clarify that the Canadian government did not, as Trudeau’s quote seems to suggest, initiate the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) because it wanted to do the right thing and uncover the truth. Survivors of the Canadian forced assimilation prisons were successful in forcing the Canadian state to create the TRC, among other things such as issuing a public apology.

After long legal battles, in May 2006, parties which included, legal counsel for former students, legal counsel for the Churches, the Assembly of First Nations, other Indigenous organizations and the Government of Canada approved the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement which began in September 2007. A critical part of this agreement was that the Canadian state would establish the TRC. Thus, it wasn’t Canada’s moral compass that drove the public inquiry into the truth of these “schools,” but rather pressure from Indigenous people and organizations, which forced the truth out of the Canadian state.

Second, many of the TRC’s Calls to Action are yet unfulfilled, and reconciliation remains an empty promise. In a recent analysis, Tom McMahon, former general legal counsel to the TRC and previously executive secretary to the Manitoba Aboriginal Justice Inquiry, lists some of the many Calls to Action that have been completely ignored by the Canadian government, including simple ones, such as creating a monument to honor the Survivors and the victims of “Residential Schools.”

More damning still, scholars Eva Jewell who is Anishinaabekwe and Ian Mosby in a recent special report concluded from their study that “In 2020 … our analysis reveals that just 8 Calls to Action have been implemented, this is down from 9 in 2019. Ultimately, we find that Canada is failing residential school Survivors and their families.” To put it bluntly, that’s a pathetic number: 8 out of 94 Calls to Action. Given this reality, how can anyone take Canada’s proclaimed commitment to reconciliation seriously?

VIDEO: Canada’s Dark Secret

These failures are not a surprise when we understand that the TRC’s Calls to Action may lead us towards the path of Indigenous sovereignty, which Canada is structured to eradicate. In other words, these failures are not shortcomings in a genuine effort towards reconciliation; they are the expected practices of a settler colonial state that has no intention of giving up its settler colonial project.

Canada is comfortable with Indigenous self-administration and cultural autonomy, especially since those structures in their current form are largely designed to further the interests of the settler colonists and not the lives of Indigenous people. However, Canada is actively opposed to decolonial Indigenous sovereignty. Canada’s “failures” in addressing its varied structural violences in fact reveals that Canada continues to claim and impose supreme settler sovereignty over Indigenous Peoples, and views any notion of a shared and layered sovereignty as a threat to its settler colonial project.

Indigenous Resurgence

Nêhiyaw poet and scholar, Erica Violet Lee recently captured in a tweet the ever resilient and admirable Indigenous resistance to settler colonialism: “In the midst of terror, know that Saskatchewan has a long, beautiful history of resistance to colonialism. Our families never quit fighting for us. Parents camped in tipis outside those residential schooling prisons, waiting to see their kids. They never gave up. Nor will we.”

So long as Canada does not recognize Indigenous sovereignty, the violence will continue, and so will Indigenous resistance and resurgence. Though depleted and continuing to face eradication today, Indigenous sovereignty has not disappeared, and will never disappear. It remains in the hearts, minds, thinking, knowing, acting, and doing of Indigenous Peoples on Turtle Island.

And it not only offers Indigenous Peoples hope, aspiration, and the drive to regenerate and resurge; it also offers the world another model, another mode of sovereignty, of living together with the land and with each other, not despite of, but across our differences and pluralities. It is a mode of sovereignty that is much more attuned to the human condition, which is one of alterity, heterogeneity, plurality, and hybridity, not absurd colonial notions of supremacy, exclusivity, and purity.