Why is it that white Australians still refuse to acknowledge the past and can’t talk about racism in the present? I thought. Oh, this denial of white privilege is hegemonic. Yes, the invisibilization of white privilege is that. I recall the white Australian founding fathers designed and wrote a political entity and constitution that excluded women, people of color, and First Nations to render a white patriarchal possession.

I remember the colonists designed the police force and prisons during British colonial and then (after Federation 1901) Australia’s frontier wars. I think to myself, disavowed still, when will we discontinue incarcerating First Nations out of the way of the white nation? Are not most people in jail there for poverty-related issues? Shouldn’t they be alleviated of poverty or given housing instead of locked up? My stomach burns as I envision abolition, a world without prisons.

My indeminably helpful cousin who sent me the photograph of our white great grandfather did so while assisting his mother, Elizabeth, my paternal aunt, pack up her home of thirty years to move into a nursing home. Melbourne and surrounding areas, as far out as my country cottage rented in West Gippsland, was ninety days into a one-hundred-and-twelve-day strict lockdown at the time. We are back in lockdown again as I write (June 2021).

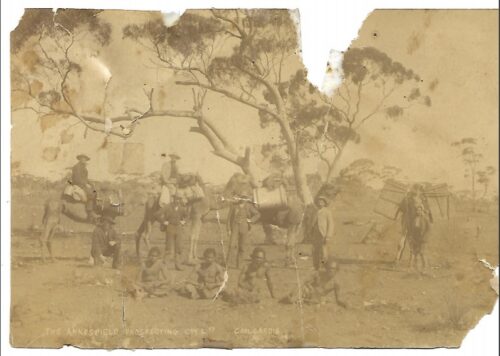

I think of my aunt’s brother, John Koerner, my deceased father, and I turn my attention back to the photo of their grandfather, John Heithersay, leading the gold prospecting expedition in Coolgardie in 1893. The image transports my senses to the land and skies from my childhood in Tennant Creek, Alice Springs, and Katherine, camping with my family and, when I was old enough, bushwalking with my father.

The four Indigenous men sitting on the ground at the front of the photograph capture my attention, sidelining happy childhood memories, safe with my father experiencing the bush’s magic he deeply loved. We were camping on stolen ground, under land rights claims in the 1970s and 1980s.

VIDEO: Systemic Racism: Australia’s great white silence

All the Indigenous men look at the camera. Their physique reminds me of my now deceased father, John Koerner (1930–2005), grandson of John Heithersay. Like the two middle-aged Indigenous men in the front row, my father was very fit in his middle age. Unlike these men, he ran marathons, kayaked, played tennis, hiked right up until his death. Of course, my father was a free man and a white Australian, but I recognized the quality of that lean, fit physique familiar to me. Dam, I miss him, I thought. I recall our last hike together on the Milford track, Aotearoa, where he died.

Did my father know about his grandfather’s prospecting expedition to Coolgardie? During the 1970s and 1980s, Dad was a public-school teacher who advocated for Indigenous children to attend and complete school. I remember he visited some of the small Aboriginal communities around Katherine, N.T., to connect with Elders and parents. Dad returned, feeling hopeful that as Principal of Katherine State High (KSH), my school, Dad, could do more.

The rights for whites aggressively desired to keep the school for their white children and keep out the Blacks.

In the process, he accrued many enemies in the N.T.; those who were quite content with Indigenous non-attendance and low graduation rates would have much preferred Dad to have let sleeping dogs lie. The rights for whites aggressively desired to keep the school for their white children and keep out the Blacks. They campaigned hard and secured government support against the Jaowyn land claim encompassing Nitmuluk Gorge and rivers. I relax as I remember the stunning Nitmuluk where Dad taught me how to swim and canoe, as families have done since the beginning of time.

Supporters of ‘Rights for Whites’ had contacts in the N.T. Government and education department whom they lobbied. When my father’s contract as Principal of Katherine State High School ended in December 1984, he was encouraged to apply for a Darwin school position, which he did. The Education Department filed the Katherine position and then offered the Darwin position to a far less experienced candidate than Dad.

Just like that, Dad was unemployed and unemployable in the N.T. education system. I remember his whole body shook with rage as we packed our car. We drove many days across the desert heart to reach the East Coast of Joh Bjelke-Peterson’s (conservative and racist Premiere for 21 years) empire of Queensland.

I continue to look at the rest of the photo. I suspect the best-dressed man is my great grandfather, John Heithersay. As far as I know, he is the only man related to me captured in this image.

While I had learned from Sue Hanson’s (Senior Linguist GALC) email that by 1910 only 20-30 Wangka people had survived the invasion and land theft, genocide; this is complex in that it seems my Great Grandfather had no weapons. Thus, he was not responsible for murder if he did not kill anyone or direct another person to kill First Nations people. The consequences of the mining as land theft and environmental destruction resulted in only 20-30 Wangka survivors at the time. How can that be anything other than genocide?

If his actions mean so many people died as a direct result? We find people guilty of manslaughter if they accidentally run over someone. The land theft is intentional. The environmental degradation is intentional and was never remedied. And who sold you the mining licence? That would be the British before Federation 1901 and Australian Governments after 1901. There was no treaty. They had no legal grounds to seize land and sell mining licences or land leases, I logicize.

I knew that John Heithersay had gone on to prosper from his gold mining activities. My great-grandfather had twelve children, including my grandmother, Elsie May. My grandmother told her daughter, Aunty Elizabeth, that when she (Elsie May) was a small girl, she used to wrap up gold nuggets as toy babies and push them around the house in her doll’s pram.

With that gold, John Heithersay bought a family home in Adelaide’s elite areas, sent his children to the best public schools through scholarships, and put his sons (not daughters) through university via scholarships. They became renowned for their academic abilities in engineering. John Heithersay mined gold in South Australia until the Great War in 1914, where, sadly, four of his sons died.

Recommended

I look at the second photo sent of John Heithersay with his four sons in 1914. I think of my grandmother (Elsie-May) who grieved her four brothers’ deaths at war. My great grandfather never returned to mining. White patriarchy kept his daughters and granddaughters from completing their education. The wealth flows to the patriarchal line designed to keep white women dependent on white men to benefit from white privilege. First Nation women, however, form matriarchal societies the sophisticated design ensure no social hierarchies, political autonomy and no poverty. Never achieved under patriarchy.

In the last week of October 2020, Victoria emerged from its 112-day lockdown response to the COVID-19 pandemic. While Victoria celebrated coming out of lockdown, I hear on The Saturday’s 7 am podcast (29/10/2020) that the Andrews Government organised the forced removal and evacuation, including arrests of Djab Wurrung people in Victoria. Djab Wurrung had held a tent embassy site in protest for several years against the Victorian Government designated removal of ancient sacred ancestor trees to make way for a highway.

1200 Australian academics sign a petition to the Victorian State Government to stop this unjustifiable travesty with more ancient trees in danger. During a climate crisis, it is nonsensical. Indeed every sacred site destroyed is further proof that the Uluru Statement from the Heart needs to be the foundational document of a new Australia. To survive the climate catastrophe, First Nations must be in the centre of everything we do. They managed this place as the first human civilizations more than 100,000 years ago, I contemplate.

Every state and territory incarcerate Indigenous peoples at the highest rates worldwide. Incarceration and police brutality continue to impact Indigenous people. The Australian Human Rights Commission Close the Gap 2020 measures show that Indigenous people’s circumstances have worsened in every area, except that where they have completed higher education, then their life expectancy is on par with non-Indigenous Australians.

2020 Close the Gap Report specified self-determination and leadership; Indigenous beliefs and knowledge; Cultural expression and continuity; Connection to Country.

The Statement of the Heart leads us through the multiple crises that face Australia, including environmental and economic. This Statement could pave the way to social, political, economic, environmental, eudemonic wellbeing, and an equitable, sustainable post-pandemic society. This Statement is the biggest, most diverse and sophisticated democratic process since the founding of Australia. The Uluru Statement could be the Heart of our shared coexistent relationality with this land, waters, skies and all beings.