The way forward in north east Syria wasn’t so clear until in early November Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan spoke with Russia’s Vladimir Putin over the phone to hash out the details of a ceasefire agreement in Nagorno Karbakh. Erdogan reportedly said that the same spirit in the agreement in Azerbaijan should be applied in Syria.

Just as Russia and Turkey began setting up the ceasefire oversight arrangements in Nagorno Karbakh, Turkey’s sights were set on Ain Issa.

Even though the town is small, it sits on a critical juncture of the M4 highway. Ain Issa is around 40 km north of Raqqa City, and sits on the M4 highway which when heading goes directly to Manbij. Ayn al Arab, known to many as Kobani, is also a few kilometers north west of Ain Issa. Sitting on this major thoroughfare the town carries much more significant for any party or group that controls it.

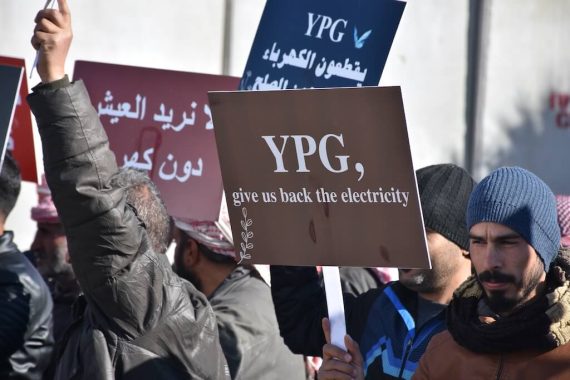

In late November reports emerged of ongoing oil sales; by the self-styled Syrian Democratic Forces, a group which Ankara believes the PKK’s Syrian wing the YPG uses to hide behind, to Assad, despite America prohibiting such sales.

The outgoing US Special Representative to Syria James Jeffrey recently said 100,000 barrels of oil are being transferred monthly to Assad controlled areas. The oil is being transferred at the behest of Husam Katerji, a Assad loyalist named in the recent American ‘Caesar’ sanctions.

It’s moved from fields in north west Syria through Tal Tamer, also on the M4 highway, to Ain Issa, then south to Raqqa city. The oil is a main source of income for the terror groups operations. An issue that hasn’t been addressed by American officials mainly due to a lack of clarity on America’s political transition following Trump’s loss to Democratic president elect Joe Biden.

That’s not the only issue that Turkey has with the YPG operations in Syria. It was only after Turkey launched Operation Peace Spring and reached an agreement with Russia in Sochi that called for the withdrawal of the YPG from specific areas including Tal Rifaat, Manbij, and the border areas east of the Euphrates River that the cracks in the YPG’s local and regional alliances began to show.

Like America before them, Russia has also failed to force YPG forces from Manbij, Tal Rifaat, and Ayn al Arab on the border. The YPG is thought be responsible for dozens of improvised explosive device (IED) attacks killing droves of civilians in Turkey backed opposition controlled areas. Recently, a YPG sleeper cell member was captured by the Turkey backed SNA and provided critical intel about those operations.

The PKK has a long history in Syria rooted in the presence of the terror group’s founder Abdullah Ocalan in Syria in the early 90s.

The PKK has a long history in Syria rooted in the presence of the terror group’s founder Abdullah Ocalan in Syria in the early 90s. Turkey nearly went to war with Syria in 1999 because the terror group was thought to be using Syria for recruitment and training.

Decades later the PKK is still leveraging its relations with Damascus to establish a foothold for itself in the Syrian geopolitical arena. It’s that historic link to Syria that the PKK and its Syrian branch the YPG are clinging to hoping that they can eventually establish an autonomous administration.

In late December 2020, the Syrian National Army’s 1st Division announced it was launching an operation to capture the small town in northern Raqqa province. Turkey-backed opposition fighters took two villages and several checkpoints north and north east of Ain Issa, 40 kilometers south the Turkey Syrian border town of Tal Abyad.

In the following days it quickly become clear that Turkey and Russia are ceasing the small window of opportunity between US administrations to pressure the YPG financially and militarily. Reports emerged that Russia and Assad offered the YPG a safe exit from Ain Issa in exchange for the Russian military and Syrian regime forces to take control.

According to local sources, the deal was presented as a means to prevent Turkey backed SNA forces from taking the town, in what is believed to be a pre requisite for Turkish Russian cooperation.

It’s not clear if the YPG has agreed to the terms of the Russian-Assad proposal but it is clear that both Turkey and Russia are not letting down their guard.

Turkey continues to reinforce front line positions north and north east of Ain Issa with the help of SNA forces. On the other hand, Russia has sent reinforcements to Ain Issa to “reduce tensions” according to Russian Ministry of Defense’s center for Syrian reconciliation.

Close cooperation between Turkey and Russia has given both nations significant strategic advantages in Libya, Azerbaijan, and Syria. Their cooperation has bothered American and NATO officials and sidelined world powers that were more influential in Syria during the past decade.

Recommended

But that cooperation is strained by a patchy history of operational flexes. The most notable of which are the 2015 downing and capture of a Russian pilot over near the Turkey-Syria border and the deadly Russian led attack on a Turkish military convoy in Idlib’s Jabal al Zawiya region that killed at least 33 Turkish soldiers in February.

While Turkey and Russia are putting the pressure on the YPG the United States has been trying to lift the YPG out of the shadows of the PKK’s terror designation. The PKK is a designated terror group in the U.S., the EU, and the UN. U.S. officials have repeatedly admitted that the American military worked with members of the group in Syria in the fight against Daesh despite knowing of their terror affiliation.

That’s why in November 2020, James Jeffrey made a final call for all PKK members to leave Syrian territory. But Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov says that America is the reason the YPG didn’t fulfill its end of the bargain in the Sochi deal.

The YPG know very well that their strongest bargaining chip are the oil fields under their control. Whether they’re trying to secure better terms with Assad and Russia or trying to convince America not to cut them loose and abandon them while they’re surrounded on all sides.

VIDEO: How Political Borders Are Redrawn in the Balkans, Caucasus and the Middle East

If all things go bad for the YPG in Ain Issa their only road out would be to the east towards Iraq. But the Iraqi government and the Kurdistan Regional Government in northern Iraq both want the YPG eliminated and have made public statements along those lines.

The consequences of this de facto reality came into light when a group of PKK fighters tried to cross into Iraq from Syria but ended badly when they faced off with KRG Peshmerga. That incident is the most revealing of all.

The fate of Ain Issa is sure to be better off than the fate of the PKK and its many facets in the region. Today, they are surrounded and alone with nowhere to run. Without any conceivable American policy in Syria or the region, Turkey and Russia, both of which are not friendly to the PKK, are further establishing themselves as geopolitical kingmakers one Ain Issa at a time.