The Iraqi Kurdistan independence referendum, which was held upon the insistence of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) President Masoud Barzani despite all the objections of local, regional and international actors, poses numerous risks that could drift the entire region into a state of chaos. The rising tension in Kirkuk after the Kirkuk governor Najmiddin Karim declared the referendum and the subsequent developments have shown how the decision to hold a referendum could drag Iraq and the region into further instability.

Tensions between the Erbil and Baghdad administrations, which have reached their peak due to the referendum decision, have also reverberated into relations between the Peshmerga forces and the Iraqi army. Peshmerga forces were not included in the anti-Daesh operations launched in Hawija, a southern district of Kirkuk. In the midst of this strained atmosphere, only a week before the referendum, a conflict broke out between the Turkmens and Kurdish groups in Kirkuk, illustrating that the tension looming over the city might culminate into a major scale conflict at any moment. In addition, the fact that the Iraqi Turkmen Front, a significant actor in the city, announced that they would not recognize the referendum, revealed that the tension between Turkmens and Kurds would not simmer down after the referendum.

As Erbil increasingly insisted on the referendum, the Baghdad administration did not hesitate in responding with hostile measures. The Iraqi Parliament discharged the Kirkuk governor from duty and vested the Iraqi Prime Minister Haidar al-Abadi with all kinds of authorities in order to protect the territorial integrity of Iraq by referring to his title of “Commander-in-Chief.” Vested with this authority, Abadi displayed that they would harshly respond to the KRG’s steps toward independence by stating a day before the referendum that the referendum is null and void. On the day of the referendum, the Iraqi Parliament assigned the Abadi government to send troops to Kirkuk. These developments highlighted that the decision-makers in Baghdad and the Abadi government have taken a determined stance concerning the referendum and the disputed territories in a coordinated and synchronized way. All these factors indicate that the disputed territories, which include Kirkuk, constitute the focal point of the referendum crisis.

The KRG administration insists on seizing control over the disputed territories by affording all the risks of conflict mainly due to the natural resources in those areas. According to the figures provided by the International Energy Agency, the overall oil reserves in the KRG region correspond to 4 billion barrels, while the inclusion of the disputed territories to the KRG will increase this amount to 45 billion barrels. Given that oil forms a large part of the KRG’s total revenues, Kirkuk’s importance for Erbil can be seen more clearly.

Another reason for the KRG’s expansionist policy in the disputed territories is the ambition to control the lowlands and the areas that are fit for cultivation aside from the highlands where Kurds are densely populated. The KRG regards the valleys that contain water resources and which are fit for cultivation, such as Tel Keppe and Zummar located in the north of Mosul, as strategic targets. Therefore, the KRG estimates that an independent Kurdish state would not be sustainable unless it includes the disputed territories.

Possible conflicts that could arise following the referendum

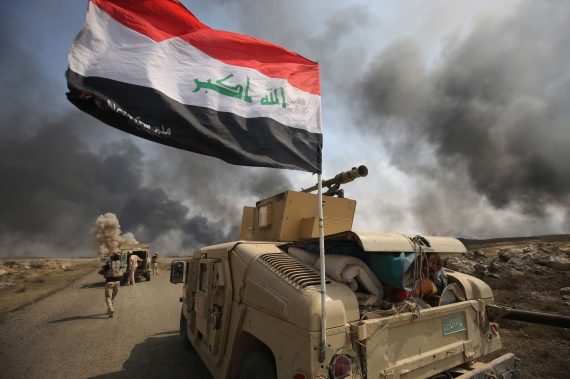

Following the referendum, conflicts could possibly break out in the disputed territories that strained the relations between the KRG and the Iraqi central administration. The Iraqi Parliament’s instructions to Abadi for intervention indicate that the disputed territories will bear witness to a sovereignty struggle in which the rivals may use force. Article 140 of the Iraqi Constitution rules holding referenda in Kirkuk and other disputed territories to determine which administration the territories will belong to. However, not all disputed territories are clearly specified in the Article. Due to this, the KRG were able to create an actual state and claim sovereignty, seizing control of a line that expands from Mosul in the west of Iraq to Mandali in the east. Before considering the requirements of organizing a referendum in these territories, it must be discussed whether the areas de facto seized by the KRG are within the disputed territories. A scenario in which these discussions cannot be finalized through negotiations might lead to a civil war. The process as of 2003 has clearly illustrated that if and when desired results cannot be obtained through negotiations, this ends in a civil war for Iraq.

A possible conflict between Baghdad and Erbil will undermine the fight against Daesh while creating a more convenient area of crisis for terror groups such as the PKK and its Syrian wing PYD. Conflict between Peshmerga and Iraqi forces may exacerbate the tension among different ethnic and religious groups in the disputed territories. Daesh and similar terror groups are likely to take advantage of such chaos and expand their domains. Besides, the PKK will want to consolidate its presence in Sinjar and make room for itself by benefiting from the crisis. The PYD stated that they would be ready to perform their duty at a possible conflict in Kirkuk, which clearly illustrates that the PKK and the PYD wish to make room for themselves by taking advantage of a possible crisis in Iraq.

The region’s countries are against the referendum

Recommended

Iraq’s neighbors, including Turkey and Iran, have adopted a strict stance against the referendum as they foresee the heavy costs of managing the potential risks of a possible independence in northern Iraq. In a statement he issued on the day the referendum was held, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan remarked that the border gate with Iraq is only open for Turkey-bound traffic, adding that some additional measures might be taken regarding the KRG’s oil transfer. In addition, it is clearly seen that Turkey has taken some critical steps in terms of economic and diplomatic sanctions considering the increasing coordination between Tehran, Baghdad and Ankara. In addition, the Turkish military launched drills near the Habur border gate, which is an important passage point between Turkey and northern Iraq, demonstrating that high level security measures have been taken with regard to the issue.

Similarly, Iran also believes that the KRG referendum threatens the stability of the entire region as well as Iraq. Therefore, the country closed its airspace to Erbil and conducted drills near the northern Iraq border ahead of the referendum. Besides, Iran displayed a determination to engage in joint action with Ankara and Baghdad concerning the developments in the KRG by pursuing heavy telephone traffic with these capitals. It was also reported that Iranian General Qasem Soleimani wanted to visit northern Iraq in order to stir negative views regarding Barzani within political circles. This indicates that Iran has also activated its influence in the field against the referendum by adopting diplomatic, economic and military measures.

Iran is also concerned about the possibility that an independent Kurdish state in northern Iraq, with ethnicity-based motives, might threaten Tehran’s control over Iranian Kurds. The country presumes that with the effect of the KRG referendum, the Iranian Kurds might demand expansion of their rights even though they do not ask for independence. An ethnicity-based instability within Iran could threaten the domestic politics of Iran in general, since Iran is a country comprising multiple ethnic groups such as Kurds, Arabs, Turks, Baloch people and various other minorities.

Another possibility that concerns Iran is the division of Iraq into three parts in case Iraqi Sunnis also found an independent state following the declaration of a Kurdish state in northern Iraq. In such a case, the Sunni state can join the anti-Iran league since they have had problems with the Shia ever since the occupation, and this would threaten the corridor Tehran has recently formed that extends through Iraq to as far as Syria and Lebanon.

Iran also estimates that it might lose its current allies if an independent Kurdish state is formed since the country has profound ideological differences with allies of the KRG. When the Iranian administration hosted a delegation of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) in Tehran in June, the PUK did not take up any stance against the referendum although the Iranian administration expressed its reservations over it. In addition, Kirkuk governor Najmiddin Karim, who is a PUK member, announced that Kirkuk would also take part in the independence vote. This development showed that Iran, which harshly stands against the referendum, could not alter the opinion of the PUK although the country is known for its close links to the political party.

All in all, given that the PUK has a secular and ethno-nationalist ideology and the public opinion acts as a determinant over the political actors in the KRG, the foundation of a Kurdish state under the leadership of Barzani would undermine Iran’s influence in the KRG.

Finally, Barzani’s amicable relations with the U.S. and Israel escalate Iran’s security concerns. Iran fears that an independent Kurdish state might act as a base for the operations to change the regime in Iran and the KRG might turn into a factor threatening the country.

Due to the clear stance of the Ankara-Tehran-Baghdad triple against the referendum and the fact that other international actors are not supporting Erbil in the current state, it seems that the Erbil administration has taken steps backward in the short term. The fact that KRG officials also emphasize negotiations and positively welcome Ayatollah Sistani’s call for “lowering the tensions and invitation for negotiations” could be interpreted as the willingness to communicate with Baghdad. Considering issues such as sovereignty in disputed areas, the extraction and sale of oil, the status of the Peshmerga within the Iraqi security forces – which are deeply rooted problems – these negotiations can turn into a means of time-gaining between Baghdad and Erbil. Nevertheless, it should not be forgotten that almost all actors in northern Iraq agree on independence and see it as their “right,” so therefore it would be wrong to expect the Erbil administration to completely eliminate the independence process. For this reason, even if negotiations begin between the two parties, it can be concluded that in the long-term the quest for independence in northern Iraq will continue to remain as an element of tension in the region.