Who would have thought that French President Emmanuel Macron and the Muslim minority living under pressure in France especially during his term, would breathe a sigh of relief at the same time, for the same reason, albeit for a temporary period! The war launched by Russian President Vladimir Putin on February 24, 2022, on the grounds of the “demilitarizing and de-Nazification of Ukraine,” turned the political climate in France upside down.

With the biggest conventional war that Europe has seen since World War II, Russians took the place of the Muslim minority in France, who were spoken of with hostility from morning to night and subjected to legal regulations one after another. Muslims, who were the target of far-right candidates in the first round of the presidential elections, could thus partially breathe because people are now more afraid of the Russians.

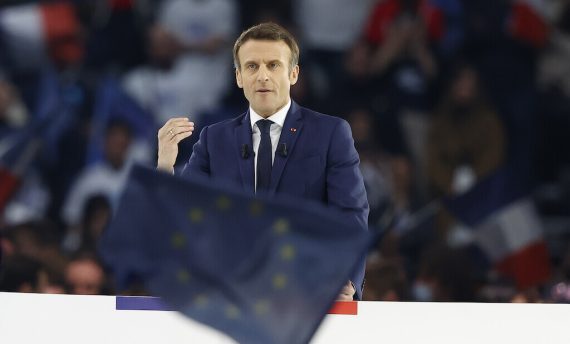

On the other hand, compared to the other candidates, President Macron, whose popularity had started decreasing as far back as directly after he was elected, turned into a dignified statesman who tried to manage the crisis in his capacity as the EU term president. Naturally, he was relieved.

After three years in which the most discriminatory laws of the Fifth Republic were enacted and anti-Islam and anti-Muslim hostility turned into a state policy, “immigrants, Islam, and Muslims” were at the forefront of the propaganda during the election campaigns.

The most media-savy and strongest candidates of the election campaign, hang on to 75-year-old former socialist militant Renaud Camus, who has turned into one of the most influential figures of the far right, and his conspiracy theory called “Le Grand Remplacement” (The Great Replacement) which claims that Arabs and Muslims will seize control of France.

This infamous theory had also influenced Brenton Tarrant, who attacked two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand in 2019, causing 51 deaths and 49 injuries. While the far-right Marine Le Pen has long expressed her admiration for Camus, Éric Zemmour, a far-right candidate who called for banning Arabic names, and giving employers the right not to employ Arabs/African, has turned Camus’s theory into the central idea of his media show and political propaganda.

As if these two weren’t enough, Valérie Pécresse, the candidate of the main center-right party of the Gaullist tradition, namely Les Républicains (The Republicans), also brought the theory of the Great Replacement to the center and engaged in identity politics. Pécresse, nicknamed “bulldozer” and self-described as “two-thirds Merkel, one-third Thatcher,” used the phrase “French on paper” for generations of immigrants and their descendants. Thus, all far-right ideas, in color and tone, have attempted to invade and poison the country.

But far-right candidates also need votes from the Republican base. For example, Le Pen tried to be a softer version of Zemmour, who, despite being both anti-Muslim and of Jewish descent, reintroduces anti-Semitic ideas. In an interview with Le Figaro newspaper, Le Pen said, “There are several Nazis around Zemmour. My goal is not to defend the village of Asterix, I promise the French people a strong country again.”

Of these three, Zemmour, who came forth by getting 7.1% of the votes, was without a doubt the most popular name. After her father Jean-Marie Le Pen, who was never screened on French television, the media also distanced itself from Marine Le Pen, but Zemmour arrived to this day as a television star in the mainstream media, after writing for years in Le Figaro, and finally hosting his own show “CNews.”

Aside from the discussion of whether the left would be a remedy in the face of this storm, where the extreme right ideas sailed into the stern, Liberation Newspaper asks: where was the left? At the beginning of the election campaign, the newspaper asked, “Well, who will protect Muslims, women, Jews, officials, intellectuals, and other targets from this hate speech?” and argued that the left should come out with an inevitable historical mission.

However, there was no reply to this article. Could Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s coming third with 22% of the total votes be an answer? The left in France has not been able to straighten its back since the socialist François Hollande, who ruled the country between 2012 and 2017.

The Socialist Party candidate, 62-year-old Anne Hidalgo, who was elected mayor of Paris in 2014, could not exceed 2% at the polls. It is not new for the French left to lose some of the working class to the far right, and to leave others in despair and make them abstain from the elections. To some, this is a lost ideological war. In fact, no leader candidate from the left could emerge with a political agenda to meet this need at a time when social democracy is most needed because of the COVID19 crisis.

Nevertheless, not on the left but on the extreme left wing, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the leader of La France insoumise (France Unbowed), was the surprise of the first round in his third run as a presidential candidate. With his promises to increase the minimum wage, to bring back a tax that was lifted for the rich, and to be positive towards the Muslim minority, he got 22% of the total votes.

Far-right ideas were seriously moving along, but Russia’s invasion of Ukraine directly affected the dynamics in French politics. As Russia claimed that its purpose was to destroy the neo-Nazis in Ukraine, far-right and right-wing candidates in France that engage in anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim propaganda were suddenly cornered. Le Pen, Zemmour, and even Mélenchon had to make people forget about their long-held admiration for Vladimir Putin and their various relations with him in person. Each tried to condemn Putin and Russia in their own way.

There was another important development revealed by the war: the immigrant was in disguise! He was no longer Arab and Muslim, but European. The commentator on the French television channel BFM put it thus, “They were not Syrians fleeing the bombings of the Syrian regime, but Europeans, with cars like ours, who simply set out to save their lives.” “Immigrants,” which was one of the most talked about topics for all candidates, including President Macron, in the election campaign, thus turned into a sensitive issue that have forced candidates to use a careful language.

Far-right candidate Zemmour said, “I would prefer the Ukrainians to be in Poland. Also, when the war is over, they can return home more easily: it is not good to destabilize France, which is drowning in immigration.” And after saying this he suddenly became “heartless”! His far-right rival Le Pen must have sensed the changing tide and and said that “Ukrainian acceptance is very natural.”

And President Macron, whose support went down right after he took his seat in the Elysée Palace, who had to struggle with the consequences of the Yellow Vest protests all over the country, who had to deal with the weaknesses in the health and industry sectors caused by the COVID19 pandemic, announced his candidacy for the elections on March 3, just five days after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

His tactic was to watch the opposition candidates from the stage and turn the first round of elections into the opposition’s primary election. Although this situation was criticized as a “democratic deficit,” he was redressed as a candidate who sought a solution to the Ukraine crisis before the Russian invasion, who tried to persuade Putin, and gave the image that he strove for peace. Thus, he assumed the most reasonable role as both the French president and the president of the EU Council.

Recommended

Macron broke away with his closest rival Le Pen, passed her by 4.7 points, and got 27.8% in the first round. Macron’s claim was to fill the seat of European leadership left vacant by Merkel and to foster France’s role in finding solutions to the problems of the European Union. Although this was opportunism and was criticized as such, until the war, the French elections were publicly discussed with headlines such as “Will Europe win the elections?” The Russia-Ukraine War changed the country’s priorities.

Macron’s famous opinion that “progress in the common defense capacity is of critical importance to ensure the sovereignty of the European Union,” which he frequently emphasized, now gained a special meaning during the war. Macron defines himself as “a defender of democracy against populism” and the only candidate who could find answers to questions such as: What red line will be drawn against the dictator who tries to seize European order? What weapons will be used to resist since there is no one ready to die for Ukraine in the European Union? What should be done for France to gain its sovereignty industrially, strategically, and militarily?

Political commentators in France put it all down to the lack of alternatives. Now the question is whether there can be a surprise in the second round.