Many policy-makers had warned of the potential Russian aggression against Ukraine, but with few exceptions nobody had expected Putin’s war jets to bomb the capital of Ukraine or the Russian army to invade Ukrainian territory. Vladimir Putin shocked the world and expectedly, this created turbulence in international politics as countries are economically interdependent. Meanwhile, Europe was faced with the tough reality of its dependency on Russian energy, slowing down its reaction time with sanctions.

For days now Russia has been bombing and trying to invade Ukrainian cities. Not only soldiers but also hundreds of civilians have been killed or injured, while hundreds of thousands have been displaced. The initial American and European reaction to the Russian invasion was weak and limited, and Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky and Ukrainians felt abandoned by their allies. European allies had hoped to deter Putin with sanctions.

Even though Biden and European leaders bragged about severe economic sanctions, this didn’t stop Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Energy export is the backbone of the Russian economy and sanctions against this sector would perhaps be the most devastating tool. However, it is unrealistic to expect the West to sanction the Russian energy trade, meaning oil and gas. Here is why.

Russian dominance over Western energy markets

In the 1960s, when Western Europe had begun to import gas from the Soviet Union, it was Western Germany that imported Soviet gas first. Over the years, as European demand for gas increased, European gas imports from the USSR increased as well. Things changed in the 1990s as states in Europe started diversifying their gas supplies and the Russian share in gas imports declined.

During that time, domestic gas production also increased in countries producing gas in Europe, notably the Netherlands, Norway, and the UK. But the amount they produced did not entirely replace Russian gas supplies; European countries’ dependence just decreased from about 90 percent to 75 percent in the late 1990s.

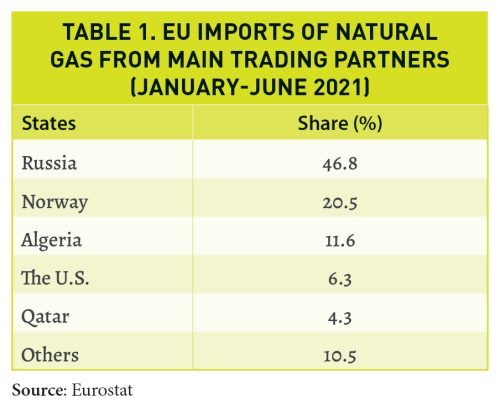

In the 2000s, liquified natural gas (LNG) became an alternative way to import gas. Europe started to construct regasification terminals. Today, led by Spain, more than 10 European countries have a total of about 210 billion cubic meters of LNG import capacity. This, however, does not mean that the EU does not import Russian gas anymore. In the first half of 2021, Russia was the main natural gas supplier of the EU with a share of 47 percent, followed by Norway with 20.5 percent.

The degree of the EU’s dependency on Russian gas differs from country to country. Eastern Europe is the most dependent on Russian gas, whereas Germany imports the most Russian gas by far. Overall, more than one third of the total of imported gas in Europe comes from Russia.

Most people confuse energy security with the security of natural gas supplies. This is a common mistake by the EU policy-makers, who focus exclusively on the gas supplies. Energy security means more: it is also about oil and coal imports. Both crude oil and petroleum products as well as coal imports by the EU are also dominated by Russia – 25 percent and 46 percent respectively.

Moreover, Europe is not the sole market that imports Russian energy products. China, along with other major Asian economies, and even the U.S., import oil and gas from Russia. Asian countries’ limited indigenous hydrocarbon resources have pushed them to turn to their energy-rich neighbor, Russia.

But due to infrastructure constraints caused by the rough geography of the U.S. that does not facilitate the construction of pipelines, the United States, the world’s number one oil and gas producer, is forced to buy both oil and gas from its ultimate rival, Russia.

Can sanctions deter Russia?

Russia is now facing critical sanctions over the invasion of Ukraine. The EU, the UK, the U.S., and Canada with many of their allies limited the Central Bank of Russia’s access to its $630 billion reserve. They also froze Putin’s and Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov’s assets in their respective countries. But putting sanctions has its limits.

The circumstances were different when the U.S. led the international community-imposed sanctions on Iran, Venezuela, or Libya – all three are members of OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries), and Iran is the second-largest producer of crude oil in the organization. But Russia is not Iran. Russia is the second-biggest producer of global oil and gas, and its supply is desperately needed to heat homes, run factories, and generate electricity in Europe.

Since the last quarter of 2021, the world has been facing severe energy shortages which pushed the gas and electricity prices to levels that have never been seen before. As part of the sanctions against Russia, the EU just targeted the oil refineries of the Russian energy sector aiming to prevent their modernization. On February 27, the EU, the UK, Canada, and the U.S. decided to remove a number of Russian banks from the SWIFT system in order to restrict their ability to do business across borders.

This is expected to bring tremendous damage to the Russian economy. But then, European capitals began to import more Russian gas via Ukraine since the sanctions still do not target energy payments.

Recommended

Time to rethink energy security in Europe

The Russian aggression in Ukraine once again has shown that the European Union deeply needs alternative energy suppliers. The fact that LNG is not a substitute for pipeline gas ties the hands of European states.

Neither Qatar, the second-biggest LNG exporter, nor the U.S., the number one natural gas producer, can replace Russian gas. It is not just about the capacity that they can supply, it is also about the European gas market structure. Many energy analysts seem unaware that the EU does not have a continent-wide natural gas transmission system. This means that we cannot talk about a single European gas market.

For instance, Spain, Europe’s largest gas liquefaction capacity holder, cannot transmit its gas to Germany or to Poland since it is disconnected from the rest of European gas infrastructure. Therefore, at the moment, LNG cannot offset the Russian pipelines’ gas. Most states with LNG facilities also import Russian LNG because it is cost-efficient.