While the United States focused on its domestic problems – primarily the sociopolitical consequences of the storming of Capitol Hill and Joe Biden’s immediate signing of executive orders and actions – Russian authorities detained the Kremlin critic Alexey Navalny upon his return to Moscow from Germany.

Western reactions to his arrest were relatively moderate, although in the future the “curious” case of Alexey Navalny could have a serious impact not only on relations between Russia and the West, but also on Russian parliamentary elections that should take place no later than September 19.

Throughout history, Russia has been ruled by tsars, monarchs, and boyars members of the highest rank of feudal aristocracies. That was even the case during the Soviet time when the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was a de facto tsar, while members of the Central Committee played the role of boyars. In modern Russia, President Vladimir Putin is often seen as a tsar.

However, Western journalists, analysts, and experts on Russia often neglect the significance of “boyars” – powerful oligarchs and members of the country’s security apparatus.

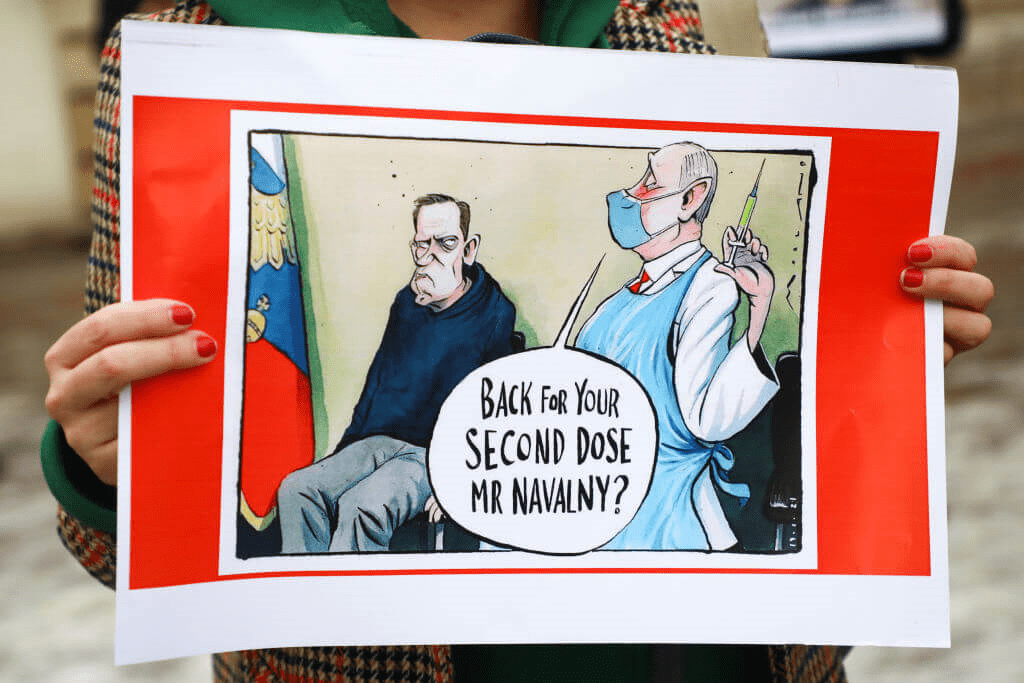

Alexey Navalny, who allegedly had been poisoned in August 2020 while on a flight from Tomsk to Moscow, hardly poses a serious threat to President Putin, especially given that his approval ratings are very low. However, his political activities may significantly jeopardize the positions of certain “boyars” who are centers of power within the Russian ruling elite.

Although the Kremlin accused Navalny of working with the CIA, Russian authorities detained the opposition figure over the alleged violations of his 2014 suspended prison sentence for embezzlement. In other words, the very fact that the Kremlin did not attempt to prove that Navalny is a “foreign agent” clearly suggests that the ultimate goal of the Russian elite may not be to completely eliminate the 44-year-old anti-corruption campaigner from political life.

This is not the first time that Navalny is behind bars. He already served several stints in jail in recent years for organizing anti-Kremlin protests. For instance, in 2015, he served 15 days for unlawfully distributing leaflets on the Moscow metro, while in February 2014 he was placed under house arrest and prohibited from communicating with anyone other than his family, lawyers, and investigators.

Unlike him, former Russian intelligence officer and the Kremlin critic Vladimir Kvachkov spent nine years in jail after he allegedly attempted to assassinate Russian politician and businessman Anatoly Chubais in 2005. However, given that Kvachkov has been very critical of the West, none of the world leaders have demanded his immediate release.

On the other hand, when pro-Western opposition politician Boris Nemtsov was murdered in February 2015, certain Western media outlets called the crime “a political murder for which Putin was responsible.” As in the case of Navalny, Russia’s leader hardly had any motives to kill a relatively unpopular opposition figure.

Vladimir Putin would unlikely benefit from Navalny’s murder, since in the eyes of the West and Russian opposition voters the Kremlin critic would become another “martyr,” or a “victim of the regime” such as whistleblower Sergei Magnitsky and the accomplished journalist Anna Politkovskaya. Still, for the West Putin will likely remain a political boogeyman, and Navalny’s arrest will be used as an additional instrument against Moscow.

New sanctions against Russia from the U.S. and the E.U. are inevitable.

In other words, new sanctions against Russia from the U.S. and the E.U. are inevitable. In the case of the United States, restrictions will be connected not only with Navalny but will likely be constantly expended, since sanctions are part of a permanent process generated by the ongoing new Cold War.

The Kremlin has already said that it will not take notice of calls from a number of Western leaders for the release of Alexey Navalny. Policy-makers in Russia are quite aware that Navalny’s release would mean his de facto victory over the system.

At the same time, it would mean that the Kremlin has succumbed to Western pressure. Thus, if the anti-corruption activist remains in prison, Moscow is expected to face a growing list of demands from the U.S. and the E.U., and it is not improbable that Russia will have to suspend or even cancel the construction of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline due to U.S. sabotage.

Recommended

Such actions will undoubtedly have an impact on Russian domestic affairs, although they will unlikely seriously affect Putin’s popularity. However, the ruling United Russia party is already widely unpopular, which creates possibilities and additional room for maneuver for Navalny’s Russia of the Future party and other so-called non-systemic opposition groups.

The two major systemic opposition parties – the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR) and the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (CP) – are expected to pass the five per cent election threshold easily and keep playing a role of the formal opposition that occasionally criticizes certain Russian officials, but never President Putin. In other words, the regime of “controlled democracy,” whose ultimate goal is elections without a change of power, will almost certainly remain intact.

On the other hand, if Navalny’s Russia of the Future party wins some seats in the Russian Duma (Parliament), Putin will have to make compromises and concessions to Vladimir Zhirinovsky and Gennady Zyuganov, the leaders of the LDPR and CP respectively, in order to neutralize Navalny’s influence in the Duma. However, there is still a long way for the Kremlin’s critic to become part of the Russian mainstream political life.

Since Russia is witnessing another Perestroika, Navalny, even imprisoned, can pose a serious threat not to Vladimir Putin whose approval ratings are still high, but to certain structures within the Russian elite – be they from the security apparatus or from powerful oligarchy – who may aim to redistribute power and wealth.

VIDEO: Russian Expansionism under Vladimir Putin