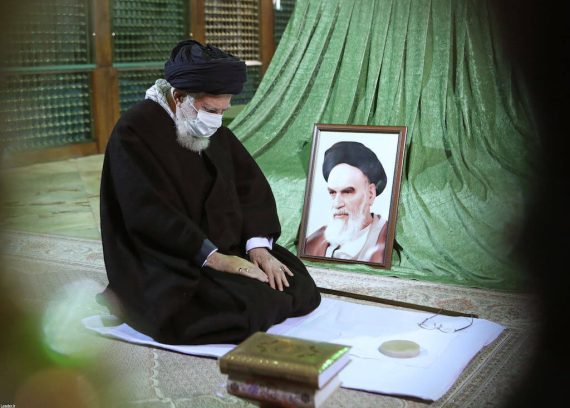

Forty-two years have passed since the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran by a referendum landslide held on March 30 and 31, 1979, when 98.2% of the country’s eligible citizens approved the new regime. A series of dramatic developments which unfolded during the last years of the Pahlavi regime ultimately brought its downfall ushering the revolutionary triumph of Ayatollah Khomeini, whose arrival back to Iran on February 1, 1979 after fourteen years of exile marked the movement’s zenith.

Immediately after his return, he made a historic speech at Behesht-e Zahra, Tehran’s famous cemetery, where he said, “I will appoint the government! I will slap the present government on the mouth! With the support of the people, I will appoint the government!” Indeed, he “slapped” the shah’s last government and held the country’s reins in a matter of days, with Prime Minister Shapour Bakhtiar resigning from his post to flee Iran shortly afterwards. Nevertheless, the long-standing chaos was far from over.

Post-revolutionary Iran

Iran is, more often than not, a puzzling case especially when it comes to its recent past. The referendum was approved by an overwhelming majority, but it did not take long for the unrestrained revolutionary enthusiasm to start to fade and an increasing number of Iranians to experience a sense of anxiety and fear which had a lot to do with the chaos that erupted after the revolution.

The situation further deteriorated by the assassinations of senior revolutionary figures, including some high-ranking ayatollahs and politicians; the trials and executions of several figures who served under the deposed shah; and the bloody struggles between the erstwhile allies of the revolutionary movements who turned into its staunch enemies after its victory. But none of these could match the horrors of the Iran-Iraq War, which lasted eight years, and brought devastating humanitarian and economic costs to both sides.

In the early 1980s, during the heat of the revolutionary turmoil, many people, including politicians, ordinary citizens, and observers at home and abroad alike, wondered if this “unlikely” revolution was “inevitable” or whether things could have followed a different path had the shah and his regime behaved more consciously. Now, more than four decades later, the more valid question is whether the Iranian revolution fulfilled its promises or not.

Retrospectively speaking, in a country where the population more than doubled from approximately 39 million in 1979 to some 83 million currently, the economic and infrastructural records of the Islamic Republic cannot be said to be worse than the Pahlavis. The same holds true for its educational and health policies. Yet, the pressures on freedoms never stopped and in time, the “revolutionary ideals” turned into viable tools for subjugating not only “the traitors” (khain) or “the enemy” (doşmen) but also ordinary Iranians including some of those who originally supported the revolution.

This never-ending revolutionary discourse hinders Iran’s normalization. During the last decades, significant progress has been made in this regard but it has fallen far behind popular expectations, especially those of Iran’s younger generations. This is the most pressing domestic challenge awaiting Iranian political elites, both from the conservative and the reformist camps. As for the outside, there are other challenges.

VIDEO: What Are the Main Political Blocs in the Middle East?

Iran in the Middle East

Obviously, the attitudes of the new regime changed Iran’s position within the international community at large – and not necessarily for the worse in all cases. As a matter of fact, had the Hostage Crisis of November 1979 not occurred between Iran and the U.S., the Islamic Republic could have been more warmly welcomed by the Western world as the shah’s image as a reasonable leader was, at least to the end of his reign, badly hurt.

Islamic Republic’s Middle East policy was not a radical shift from the previous era, at least in terms of its objectives.

But even so, Iran’s capacity as a principal oil exporter, its geostrategic location, and the economic interests of many European states in the country, gave it enough room for maneuver in international politics. To this, Iran’s major role in Middle Eastern politics should also be added.

From a broader historical perspective, the Islamic Republic’s Middle East policy was not, from the beginning, a radical shift from the previous era, at least in terms of its objectives. Yet, the means and the discourse used for this policy were revolutionary. In the thick of the war against Iraq, Ayatollah Khomeini said that they were not after conquering the world and that they wanted to share pains with Muslims. “We do not want to go anywhere to capture it… We are defending Islam… Saddam is oppressing his own people. We are not attacking; at this we are in a defensive position.”

Evidently, although the war was originally started by Saddam Hussein, it could have stopped much earlier and at lower costs for both sides had Iran not shifted from a defensive position to an offensive one at some stage of the war. Equally significant was the lesson Iran’s leaders learnt from the war which, they thought, was “imposed” on them.

Recommended

During the war, Iranian leaders felt that they were left to their fate by most of the Arab regimes which, they thought, strove for the Islamic Republic’s downfall with the notable exception of Hafez al-Assad’s Syria. He had his reasons to hate Saddam more than the Islamic Republic that was eager to align with him. Khomeini died in 1989, about a year after the war was over, and was replaced by President Ali Khamenei as Iran’s new supreme leader. Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, a relatively moderate figure, emerged victorious in the 1989 presidential elections to be Iran’s fourth president.

Now Iran seemed to follow a different path in its regional policies. Nonetheless, the growing presence of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps in the region, the emergence of Lebanese Hezbollah in the early 1980s with Iran’s full backing, and the unwillingness of some Arab regimes including, but not limited to, Egypt and Saudi Arabia, for a rapprochement with a “revolution-exporting Iran” undermined the prospects for normalization throughout the 1990s.

Moreover, faced by the threats posed by the U.S. and Israel, Iran adopted an extensive armament policy to the further concern of its neighbors. The 21st century opened an entirely different page for Iran’s presence in the Middle East.

The turn of the century unfolded two rather paradoxical developments. On the one hand, Iran’s nuclear program came to the attention of the U.S. and the rest of the international community at a time when Saddam was soon to be blamed for having weapons of mass destruction. On the other, the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan (2001) and Iraq (2003) after 9/11, eliminated two of Iran’s archenemies: the Taliban and Saddam respectively.

The long border between Iran and Iraq along with Iran’s religious affinity with certain Shiite groups inside Iraq enabled the former to gain an unprecedented ground in Iraq making it impossible to secure Iraq’s stability without Iran’s involvement. Here too the elite Quds Forces of the Revolutionary Guards played the leading role in arming the Iran-backed groups and further destabilizing the already turbulent Iraq.

Their role in Syria, however, was no less significant. When the Arab Spring broke out in 2011, Iran celebrated it as an “Islamic awakening” and drew parallels with the Islamic Revolution. But this early idealistic optimism soon shattered and turned into an uncompromising realism in defense of Bashar al-Assad and his regime.

In the meantime, Iran has supported the Houthis, a predominately Zaidi Shia force in northern Yemen, in their fight against Ali Abdullah Saleh, the country’s former president. With the equally devastating involvement of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates in the domestic war, the Yemeni crisis turned into a full-fledged humanitarian crisis.

There is still no solid ground for finding a sustainable solution to the distressing regional problems, and there are far-reaching uncertainties in war-driven countries such as Syria, Yemen, Libya, and Iraq. Iran’s participation is necessary for finding a solution to any of these crises. Yet, I regret to repeat what I said here more than two years ago, but sustainable regional peace is still a distant dream under the present circumstances.