In Iran, painting and other forms of visual arts have a long-standing tradition with graphic design being significantly more pervasive than painting. In mosques, public buildings, and shrines, there is a large work of visual art based on Persian calligraphy.

In addition to sculptural reliefs with political messages that were produced in pre-Islamic Iran and continued up to the 19th century, and political murals, a new visual movement emerged with political references to the late modern period in Iran.

In the late modern era and with the arrival and spread of modern art from Europe to Iran, the tradition of political illustration continued, and a large number of portraits of kings and courtiers became popular in Iran. In recent decades, with Iran’s further urbanization, these images and portraits have found their way into Iran’s streets and public spaces.

During the political conflicts leading up to the 1979 Revolution, murals and graffiti played an essential role in conveying the revolution’s messages. It should be noted that Iran experienced a growth and revival in numerous artistic fields in the 1960s and 1970s, and a number of idealistic artists, primarily adhering to left-wing and anti-Western ideas, emerged and sought to create a kind of revolutionary identity and utopian society.

Among these artists were several graphic artists and painters who sought to depict publicly the shah’s symbols and capitalism’s oppression. In other words, this movement, which arose after the democratization of arts and its removal from the monopoly of the elites, became a prominent feature of Iranian public culture. In the first years after the revolution and during the relative political freedom of those years, we see a considerable volume of visual works of art.

Due to political restrictions that gradually emerged after the revolution, diversity and multivocality in visual productions faded away. With the migration of artists abroad and the prominence of a more ideological political power after the revolution, only a limited number of artists were permitted to enter the public arena.

In parallel with these changes in the balance of power, the Iran-Iraq War began and lasted eight years. Many Iranian volunteers joined the war fronts and, in many cases, were killed. Therefore, the images of “martyrs” became the most visible icons of public spaces.

In the 1980s and 1990s, almost all public urban areas in Iran displayed the images of Ayatollah Khomeini and the war’s martyrs. In addition, symbols of opposition to the West, especially to the U.S. government, were prominent on many of Iran’s streets. These images were often murals painted on the walls of tall buildings.

The works were usually anonymous and it is not easy to locate the artists’ traces today. An academic study has argued that after the revolution, the murals of martyrs were part of memorial and political propaganda campaigns. The artists combined the images of martyrs with inscriptions. The harmony of these murals with their surrounding environment was limited, and they maintained a moderate connection with the audience.

In the 2000s and 2010s, these political murals changed fundamentally. On the one hand, the advent of new technology made it possible to print large-scale images digitally. On the other, a new generation of painters and graphic artists emerged. These changes were accompanied by alterations in the power structure of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Imported digital printing machines allowed images to be presented in large numbers, and new computer software allowed designers to create various types of political icons. However, more importantly, the recent changes in power relations allowed a particular group of designers to present their work publicly.

The emergence of a kind of deep state in Iran in the 2010s, which had access to various budgets, tools, and privileges, led to a massive change in Iran’s political murals and visual culture. It started with the acquisition of large city billboards and the appearance of portraying radical works of graphic design. Although in many cases the city councils, municipalities, and the Iranian Ministry of Interior were in the hands of the reformists, it was the powerful conservative groups that held the major public and urban venues and could display their icons and symbols. This time, these groups offered the facilities to a limited group of artists.

At the same time, they gathered these groups of artists in their affiliated organizations and presented only their work in public spaces. In other words, once again, works of art lost their democratic essence. In terms of content, this artwork did not present the image of martyrs, which enjoyed a general consensus by Iranians, but instead became a propaganda tool of the Iranian deep state.

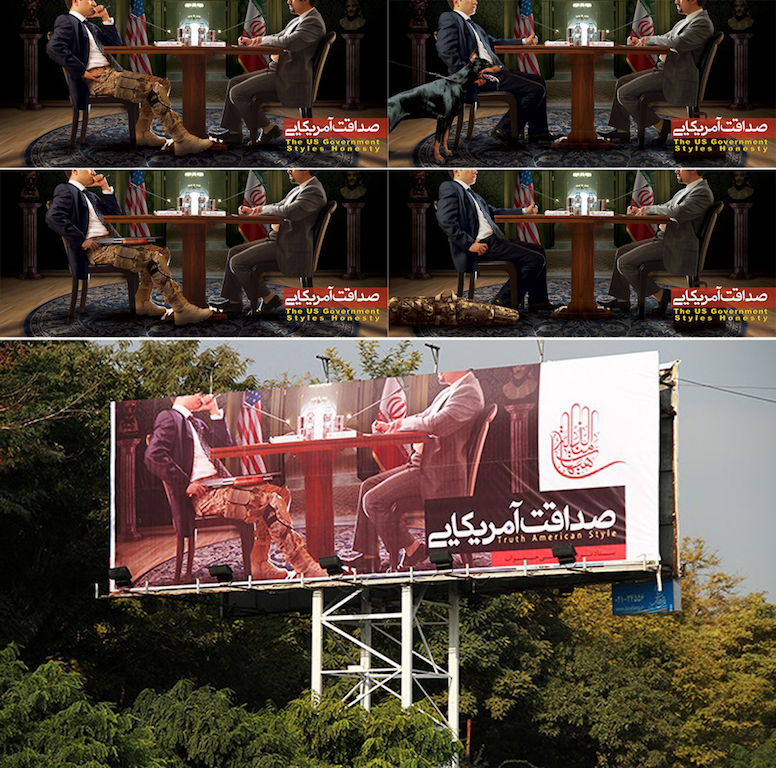

An example of the new institutions dedicated to this visual propaganda is the House of Designers of the Islamic Revolution, which began its work in 2012. During the negotiations between Iran and the P5+1, which led to the signing of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), the House of Designers installed billboards entitled American Honesty in Iranian cities.

In one of the compositions, two men are seen sitting opposite each other at a table. Although they are both wearing suits on their upper bodies, one of them is wearing military combat pants and is pointing a rifle under the table at the other. Based on the visible part of his face, the person to whom the rifle is pointed towards under the table has a goatee and a collar similar to those of Iranian diplomats. The man, in fact, has similarities with Dr. Javad Zarif, the minister of foreign affairs of Iran.

The flags in the background indicate the two figures at the table are an Iranian and an American negotiator. The billboards were installed on pedestrian overpasses and walls in Tehran, Isfahan, Mashhad and other Iranian major cities and were quickly removed from cities due to objections by the Iranian government and nuclear negotiators. However, a report by Mashregh News Agency confirmed that Ayatollah Khamenei praised the posters in his meetings with some “young designers” and expressed his disapproval of their removal.

As Iran’s political atmosphere has become more radical in recent years, political visual representations have also evolved into more extreme versions and have moved towards increasing support for less popular but influential groups in power. Thus, over the years, we have seen that in some cases, these works have provoked an adverse reaction in Iranian society.

In such cases, sections of society have felt insulted by these images or have felt that their religious and national beliefs have been affronted. An example is a group of billboard images installed in Tehran metro stations in which revolutionary figures were presented as similar to the companions of Hussein, the grandson of Prophet Muhammad. The billboards were uninstalled due to the vast objection of the traditionally apolitical religious forces.

In other cases, the people behind these graphic designs have been accused of not including women or of mitigating their role. Given the power of conservative groups and the “deep state” in Iran and their dominance over propaganda tools, these unfamiliar and challenging visuals and content have appeared in the most important squares of large cities, especially Tehran, at entrances to mosques, metro stations, and on railway carriages.

In recent years, the widespread use of social media and communication outlets, particularly the instant messaging service Telegram, has drastically diminished the influence of official murals. Today, the visual representations in streets and public thoroughfares do not form a significant part of people’s visual memory; their effect has been diminished by the vast number of visual items available on the Internet.

On the other hand, because many of these murals do not reflect most citizens’ political opinions, certain citizens who traditionally support the state propaganda are influenced by them. It seems that in the future, the appearance of such murals will continue. Yet, the process of displaying these graphic designs with the same or even more ideological and radical approaches seems to be meeting with obstacles, and their influence seems doomed to diminish.

Recommended