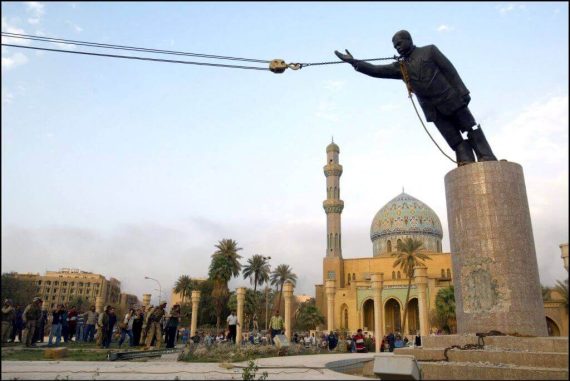

Throughout February, the Saudi Arabian-owned and UAE-based Al Arabiya channel aired two interviews with Raghad Saddam Hussein. For those who think her name sounds familiar, that is because she is the daughter of the late and deposed Iraqi dictator, Saddam Hussein, who ruled Iraq from 1979 until an illegal US-led invasion toppled him and his Ba’athist regime in 2003, allegedly on a mission to bring democracy to Iraq and to disarm its weapons of mass destruction (WMDs).

Of course, both democracy in Iraq and any functioning WMD programme turned out to be not only illusory, but an outright lie. Iraq’s governance is now at the mercy of a number of corrupt political elites, many of whom owe their allegiances and careers to neighbouring Iran’s support.

So why are these politicians so afraid of what a dead dictator’s daughter might have to say?

Whereas it would previously take several dollars to equal a single dinar, in the modern day it now takes thousands of dinars to make a single dollar, with current prices currently at $1,458 to the dinar. The Iraqi economy is in appalling shape, with a bloated public sector, very little foreign investment, and a corrupt system that awards large contracts to ethically compromised businessmen who have ties to politicians who enjoy substantial kickbacks.

Raghad’s appearance on a regional pan-Arab broadcaster has caused a massive debate in Iraq.

After being almost totally eradicated, illiteracy has made a resurgent comeback with almost 10 percent of the country over the age of 15 unable to read and write, with gender inequality surging and causing female illiteracy to be almost double that of their male counterparts, according to UNESCO. Meanwhile, Iraqis who are literate, have achieved academically, and who are trying to teach the future generations of their nation are commonly targeted for assassination, leading to a brain drain.

Raghad’s appearance on a regional pan-Arab broadcaster has caused a massive debate in Iraq, with some feeling nostalgic for the days when, despite living under a brutal dictator, Iraqis still had equal access to education, physical security to go about their business, and public services that, while not ideal under a sanctions regime, still blows almost anything the modern Iraqi government offers today out of the water.

VIDEO: Exclusive interview with Raghad Saddam Hussein

Iran’s stooges fear any alternative to their rule

But, of course, Raghad’s interviews also come at a time when the political power players in Baghdad are facing their most significant threat since the forces of the so-called Islamic State, or Daesh, almost captured the Iraqi capital in 2014.

Since 2019, predominantly Shia Arab demonstrators have repeatedly taken to the streets to protest their political elites who have mired their country in corruption, squandered its wealth, and drowned it in a sea of blood while serving the interests of foreign powers, particularly Iran.

Recommended

Rather than respond with reforms, the Iraqi authorities deployed their security forces, killing more than 600 civilians. They were aided by Shia jihadist militias, all loyal to Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and who protect and support Tehran’s agenda of control over Iraq.

Protests against the failed political system that seemingly only serves the interests of the US and Iran have been taking place for more than a decade in Iraq.

Protests against the failed political system that seemingly only serves the interests of the US and Iran have been taking place for more than a decade, with repeated Sunni-led demonstrations meeting heavy crackdowns and deadly violence. The last such attempt was savagely ended by sectarian Shia Islamist Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, a well-known Iranian stooge, who ordered the army into the protest camps in 2013 and opened the door to armed violence which ultimately led to Daesh’s conquest of a third of the country.

While previous Shia-led governments could easily smear Sunni protesters as being sympathisers of either the Ba’athists, Al-Qaeda, or even Daesh, and could use that as a cover to violently suppress them, it has proven much more difficult to do that to the Shia demonstrators who, by and large, were the electoral heartland for most of those in power over close to two decades. It is for that reason that protests continue, with the authorities recently killing four demonstrators in the Shia majority city of Nasiriyah late last month.

In a country such as this, where the political elite are viewed across the ethno-sectarian divide as serving no one’s interests but themselves, is it any wonder that the mere voice of Saddam’s daughter elicits such spasmodic fear?

Despite Saddam’s many well-documented cruelties, the situation in Iraq is so bad that the halls of power in Baghdad still fear the phantom of Saddam that continues to stalk his old palatial complexes, now inhabited by those who sold Iraq out to serve their own interests and having achieved nothing for Iraqis in almost two decades.

It is for that reason that Raghad’s interview, her apportioning blame on Iran’s presence for much of Iraq’s woes, and her open consideration of perhaps a political role in Iraq’s future has so many of Baghdad’s elites agitated and laying awake at night.