The Istanbul Convention (IC) is a convention by the Council of Europe on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence. It has been signed by 45 countries, but 11 – including the United Kingdom – are yet to ratify it. Countries such as Poland, Bulgaria, and Slovakia have been planning to halt their plans to ratify the convention because of “elements of ideological nature,” which the Polish Minister of Justice has declared to be harmful.

Bulgaria, too, is struggling with constitutional troubles regarding the convention. The U.K. government signed the convention nearly a decade ago but is progressing slowly toward its ratification. Turkey was the first country to ratify the convention but recently officially withdrew from it.

The U.K. and the Istanbul Convention

When a government decides to ratify a convention, the state is legally bound to follow it and there is a time frame granted to enact the necessary legislation in order to give a treaty domestic effect. With regard to the U.K.’s progress towards the ratification of the Istanbul Convention, there are three articles whose terms the country hasn’t fulfilled; these are Articles 44, 59, and 4(3).

Article 44 rules that “(1) parties shall take the necessary legislative or other measures to establish jurisdiction over any offense established in accordance with this Convention, when the offense is committed: a) in their territory; or b) on board a ship flying their flag; or c) on board an aircraft registered under their laws; or d) by one of their nationals; or e) by a person who has her or his habitual residence in their territory.”

VIDEO: Poland wants to abandon the application of the Istanbul Convention

This means that Article 44 of the Istanbul Convention gives provision for countries to initiate jurisdiction over a crime committed by one of their nationals outside the country. However, the United Kingdom already exercises territorial jurisdiction over crimes such as forced marriage, female genital mutilation (FGM), and trafficking, which are also crucial parts of the convention. Besides these, there are crimes such as rape, sexual assault, and domestic violence where the U.K.’s jurisdiction does not apply and in order to comply with the convention, changes in its domestic laws are required.

Articles 59 and 4(3)

Currently, people with certain visas (such as spousal or fiancé visas) in the U.K. have “no recourse to public funds” which means that as foreigners they might not be able to apply for all U.K. benefits or services. For this reason, the Istanbul Convention’s Articles 59, which refers to residency status, and 4(3) remain marked as “under review” since the European treaty demands that services and support for victims must not discriminate on the basis of residency or immigration status.

Ratifying the Istanbul Convention would mean that the U.K. government has to take serious actions to change its domestic legislation. Even though these changes need time, it is remarkable that the U.K. has been struggling – or has been passive – regarding changing its domestic laws regarding this issue for nearly a decade. According to the progress report published in 2017, the UK government stated, “We will only take steps toward ratification when we are absolutely satisfied that the UK complies with all articles of the Convention.”

The progress report includes information on the measures to be taken and legislation required to enable the U.K. to ratify the convention. The IC Change, which is a volunteer-led campaign calling on the U.K. government to ratify the Istanbul Convention, criticized the report as being short and missing a series of points. In June 2021, the U.K. will mark eight years since the government signed the Istanbul Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence.

In Belgium, 300,000 women are victims of domestic violence and around 150 women are murdered every year.

How Effective Is the Istanbul Convention?

In the Netherlands and Belgium, the Istanbul Convention entered into force in 2016. According to a Dutch research in 2020, every ten days a woman in the Netherlands dies as a result of domestic violence. Kirsten van den Hul, former member of parliament for the Labour Party (PvdA), stated that there is a misconception about the nature of the problem. She claims, “People often think of certain cultures or classes, but violence against women and girls happens everywhere. This includes Europe and the Netherlands. Even with highly educated white people.”

In Belgium, 300,000 women are victims of domestic violence and around 150 women are murdered every year. Magda De Meyer, Chairman of the National Women’s Council, stated, “If you see that femicide claims more victims than terrorism, why isn’t it higher on the agenda?” Journalist and writer Kris Smet stated that the femicide of women is “absolutely ridiculous in this civilized country” and that “there is still a lot of work to be done here.”

Recommended

According to French Minister of Justice Éric Dupond-Moretti, last year in France, “106 domestic crimes were committed in which 90 of the victims were women.” All the women victims were killed by their ex-spouses.

In Germany, according to Deutsche Welle, every day, a man tries to kill his partner or ex-partner. One in three attempts is successful in the country. Vanessa Bell from the NGO Terre des Femmes has claimed that “femicide is still a taboo topic in Germany.”

Even though all the above countries have ratified the Istanbul Convention for a while now, it is remarkable that there has not been a dramatic change or decrease in offenses and cases of femicide. It is also clear that conservative intellectuals in several countries feel that the current direction of the European Union on societal issues will mean a further crumbling of its Christian or Islamic identity and conservative values.

Slovakia, for example, joined the Istanbul Convention in 2011, but hasn’t ratified it yet. According to Slovakia’s Prime Minister Robert Fico, the government maintains the right not to ratify the convention. He added that Europe can’t implement measures against the sensitivities and beliefs of individuals in member states. Fico stated that as long as he is prime minister, if concerns regarding the interpretation of controversial provisions are not addressed and, in particular, if the definition of marriage as a union between a man and a woman is not adopted, he will “never ever” give consent to submit this agreement for ratification.

Krasimir Karakachanov, the Bulgarian Minister of Defence, claimed that through the convention “international lobbies are pushing Bulgaria to legalize a ‘third gender’ and introduce school programs for studying homosexuality and transvestism and creating opportunities for enforcing same-sex marriages.” In addition, the Bulgarian Socialist Party and the Bulgarian Orthodox Church have turned against the convention as well.

Lakshmi Puri, Deputy Executive Director of UN Women, who was a keynote speaker at the 57th session of the Commission on the Status of Women (CSW57) organized by the United Nations, said that beyond the legal basis that a convention provides, the convention also has a “symbolic” importance. However, this stance raises questions. Does not ratifying the convention necessarily mean paying less attention to women’s inviolable human rights? Isn’t there another way for non-ratifying countries to express their worries and support regarding violence against women?

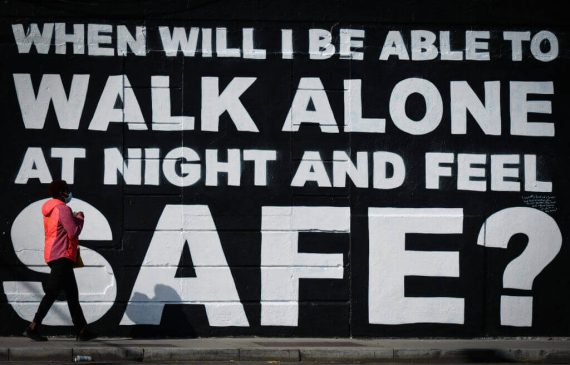

What works for one state might not work for another, another, and on the whole the issue requires closer attention. Since it seems clear that some governments do not intend to ratify the convention in the long term, these governments should be given the space to figure out their own administrative measures and explore the possibilities within their legal systems to stop femicide in their countries. Instead of having a never-ending debate of whether to ratify the Istanbul Convention or not, states need to prioritize ending violence against women by any means possible. For many women this needs to happen today – tomorrow might be too late.