As Turkey moves towards its first presidential election, which will be held on 24 June, the political parties including the secularist People’s Republican Party (CHP), the nationalist Good Party (Iyi Party), the Islamist Felicity Party (SP), and the Kurdish nationalist Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) have struggled to team up against the alliance between the ruling Justice and Development Party (AK Party) and the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP). Every alliance needs an ideological basis and the alliance among the opposition parties in Turkey is not an exception. However, the existing ideological distance between the parties poses a serious obstacle for them to form a working alliance.

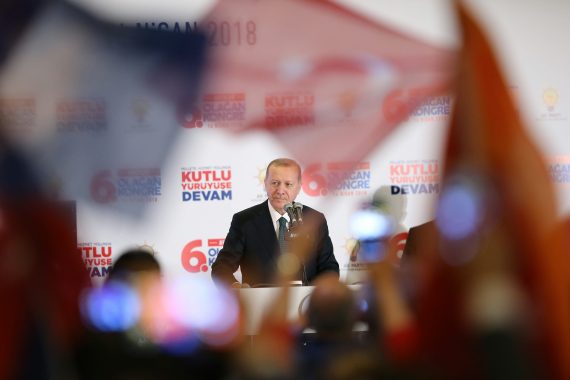

This lack of shared ideological basis is sought to be evaded by resorting to negative politics, which is shaped around the principles such as democracy. And democracy is defined by a strategic goal with reference to opposing one-man rule, more particularly, Turkey’s shift to a presidential system and its main actor President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. This equivalence between democracy and anti-Erdoganism might mobilize some sections of society, especially the loyal supporters of these parties. However, it falls short of persuading the majority of non-partisan, MHP constituents and the AK Party supporters. Not to mention the expected loss of votes owing to ideological contradictions among themselves.

Hence, the combined electoral support given to the alliance does not reach fifty percent of votes. This means that anti-Erdoganism is not enough to get the opposition to win the elections. There are two main reasons for why anti-Erdoganism is not sufficient for the opposition to get what they want. First of all, anti-Erdoganism is to be equivalent to democracy and Erdogan’s leadership in Turkey and the presidential system he backs are supposed to violate the fundamental principle of democracy, which is keeping the place of power empty. The AK Party rule for 15-plus years has complied with this principle of democracy. AK Party’s political life has been shaped around consolidating democracy by rolling back the military tutelage and extending the sphere of politics. And this politics of democratization has consistently attracted an ardent support from Turkish society.

Recommended

Besides, the presidential system in Turkey allows for the presence of the opposition, agrees to share power and transfer it through free and fair elections, and abides by the democratic norms of separation of powers and the rule of law. The acquisition of one-man rule, therefore, does not live up to the requirements of a genuine one-man rule. Indeed, a system might be considered a man-rule, first of all, if it does not allow for a multi-party system and free elections. It needs to reject sharing power and transferring it. Secondly, a system can be described as one-man rule if it rejects checks and balances and the rule of law. That is, the rule must be arbitrary. The strong execution does not necessarily mean a one-man rule. This is what the opposition fails to grasp and tends to confuse about the presidential system in Turkey. The transition to this system received popular support and approval in the referendum on 16 April, 2017.

The second reason why anti-Erdoganism serves poorly for the opposition stems from the fact that democratic politics requires the creation of new societal demands or bringing the majority of existing societal demands together in a single political project. One can admit that despite its limited scope, the anti-Erdogan alliance brings some societal demands together. If anti-Erdoganism succeeds, the CHP believes that the “old Turkey,” which was shaped around the military tutelage, could be reinstituted and that the CHP would easily hold on to power. The HDP, too, thinks that the return of the old Turkey would create a political situation where the alienation of Kurds from the Turkish state and creation of an independent “Kurdistan” under the control of the PKK could be more likely. In the same vein, the Iyi Party feels very nostalgic about the old Turkey where the bureaucracy used to call the shots whereas the SP believes the return of the old Turkey would make it once again the main opposition party.

Sadly, the support for the old Turkey in Turkish society is not that large. Turkish society demands the further consolidation of democracy in national politics, justice in redistribution of wealth, development in the economic sphere and a powerful and autonomous Turkish state in regional and international politics. Anti-Erdoganism is far from responding to these societal demands and this makes it a poor idea in creating the largest and most inclusive power bloc in Turkish politics. If the opposition does not give up its polarization politics, it will most likely meet a decisive defeat in the upcoming election.