W

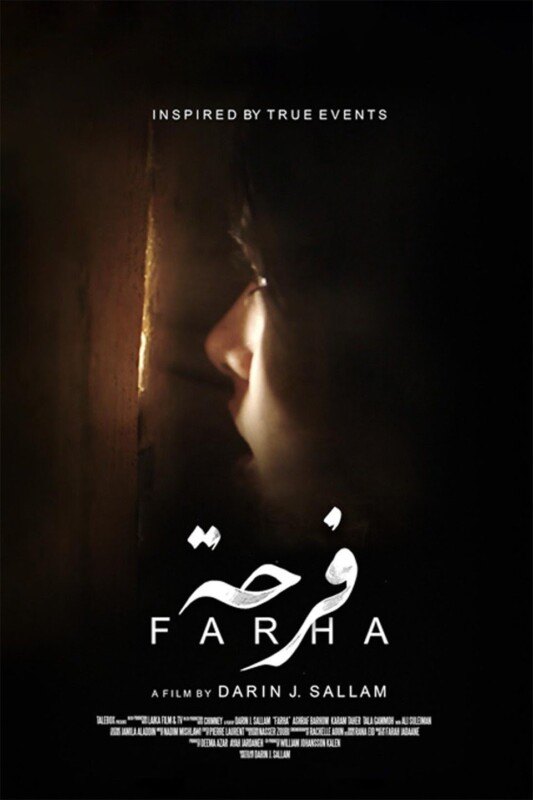

hen the Guardian reported on the negative Israeli reaction to the Netflix release of the film Farha (2021), the debut feature by Palestinian-Jordanian director Darin J. Sallam, they gave away a crucial part of the plot. It is difficult to discern whether this was a deliberate act of sabotage to ruin the film for potential viewers or a clumsy mistake by Bethan McKernan, the Guardian’s Jerusalem correspondent.

What is undeniable is that there has been a concerted effort to rubbish the film and suppress it. Just before the film was released worldwide on Netflix, hundreds of spam accounts left negative reviews on IMDb in what the Middle East Eye described as an “organized campaign.” Furthermore, Avigdor Lieberman, Israel’s minister of finance, described Netflix’s decision to platform it as “crazy.”

So why has this film created so much controversy? Not to repeat McKernan’s mistake, I advise the reader to watch the film before reading any further. I will be analyzing the film in some detail in what follows so as to work out why it has unnerved so many and in order to tackle some of the criticism that has been leveled against it. I first watched Farha on the opening night of the 2022 Safar Film Festival in London, knowing nothing about it beforehand—I believe is the ideal way to experience this film.

The film is set in Palestine in 1948. Fourteen-year-old Farha (Karam Taher) wants her father (Ashraf Barhoum), the mayor of their small village, to allow her to continue her education in the city. Her uncle (Ali Suliman) argues in favor of Farha being educated rather than married off and the father eventually agrees. Just as Farha is on the cusp of achieving her dream, her village is attacked by Zionists. It’s a testimony to the filmmaking that you could be fooled into thinking you have seen extensive battle scenes when much of the war is implied through sound rather than image. Farha’s father locks her in a pantry for her own safety and seals the door. He promises to return at a later time.

We begin to feel Farha’s increasing claustrophobia. Everything is a challenge: from finding a light source to collecting rainwater through a hole in the wall and solving the problem of how to go to the toilet in such a confined space. All this happens almost silently or with very effective use of sound. It is pure cinema that allows us to get close to Farha as we experience the visceral intensity of being confined with her. We long for her to find a way to break the door.

Then, through a gap in the door, Farha witnesses the arrival of a family. A woman gives birth. Farha calls out for the father of the family. Just as we think he is going to rescue her, Zionist soldiers arrive. The film goes from second gear into fifth. Every passing second the tension mounts. The danger the soldiers represent is palpable. At one point, a female soldier reaches inside the garment of the Palestinian woman who gave birth and extracts the large, heavy metallic key to her house tied around her neck. The soldier teases her by telling her she can keep it as a souvenir, implying she will never see her home again.

The family is eventually lined up and shot. We don’t see the moment of their execution, only the reaction on Farha’s face as she witnesses the horror. Then comes the crucial part, the part McKernan ruined for the Guardian readers: the newborn baby is left behind. A young Jewish soldier is ordered to kill him without wasting a bullet. He contemplates stomping on the baby, but in the end leaves a handkerchief over him and joins his departing unit. Finally, when Farha finds a hidden gun and blows open the door, she discovers flies feasting on the dead baby’s corpse.

With such a powerful, unflinching story, the Israeli reaction to Farha is perhaps not surprising. The irony is that much of Sallam’s secondary research on the events of 1948, which the Palestinians refer to as “Al-Nakba” (The Catastrophe), came from the work of Israeli historians such as Ilan Pappé. The violent expulsion of some 750,000 plus Palestinians from their villages which led to the creation of Israel is hardly a secret. The Israeli denial is a testimony to the power of the film.

What is surprising are some of the negative reviews the film has received in the Arab press. Some have critiqued the film for pandering to Western orientalism by having a young girl longing to be educated and being denied that right by her Arab community—but those critics misread the early scenes. The film shows Farha’s struggle but also her triumph. She persuades her father to let her be educated and you feel that he is secretly proud of her “stubbornness.”

The film is very clear about the fact that her education wasn’t so much interrupted by her community but by the attack on her village by the occupying forces. The uncle who helped persuade her father to allow her to be educated turns out in the end to be an informant for the Zionist soldiers. This irked some critics who perhaps would have preferred for all Palestinians in the film to be depicted as heroes rather than as complex characters. The uncle, realizing that the Zionist soldiers lied to him about their intention, breaks down at one point. He reminds us that no one thought the destruction of Palestine was going to be so remorseless and complete.

The film was further criticized for being directed towards the Western viewer rather than the Arab viewer. Here, the Arab critics assume that the film’s release on Netflix was inevitable. However, when I met Sallam at the Safar Film Festival, she had no idea what further life the film was going to have beyond the film festival circuit. Netflix is now a global platform and the film was amongst the top ten in several Arab countries, so the implied inauthenticity just doesn’t wash.

There was also criticism that the film focuses on an individual rather than the collective. But before Farha’s confinement, the film allows us to get a sense of her entire community, including Palestinian fighters who visit her mayor father to persuade him, unsuccessfully, to join their fight. Farha is not just a heroine we are rooting for—she is our conduit to the act of witnessing history as it unfolds. The notion that a hero’s journey denies the collective, strikes me, as an insult to the viewer’s intelligence who can discern the collective narrative through the individual.

Recommended

What is more, from a practical point of view, when making a film on a limited budget, it becomes prohibitive to tell a collective story. The cleverness of Farha is that it takes the complex history of the Nakba and distils it into a single, focused story. Sallam has said in interviews that she inherited the true story, upon which she based Farha, from her family. Had she tried to tell the story in a more collective way, she would have lost her artistic connection to the core of it which is about a teenage girl’s confinement while war breaks out around her. The Arab critics are demanding too much from this single film which is only an hour and a half long, and perhaps their harsh critique is a reaction to being confronted with such a deeply repressed traumatic story.

Another film about the Nakba that I have seen is The Time That Remains (2009), a semi-autobiographical work written and directed by Palestinian filmmaker Elia Suleiman. It is a funny, surreal, subtle film that moves between the events of 1948 and present-day Israel. If a charge can be levelled against Farha, it is that it is not as subtle asThe Time That Remains is. Farha is designed to hit you in the gut; it is intended to be a visceral experience, not an act of meditation.

The repercussions of the Nakba sadly remain with us to this day. Every time you see Gaza being bombed or a video of an Israeli soldier executing a Palestinian on Twitter, you’re witnessing the reverberation of the big bang that is the Nakba. Without looking honestly, deeply, and thoroughly at that history, the wounds created by it will never heal. We need more films like Farha.