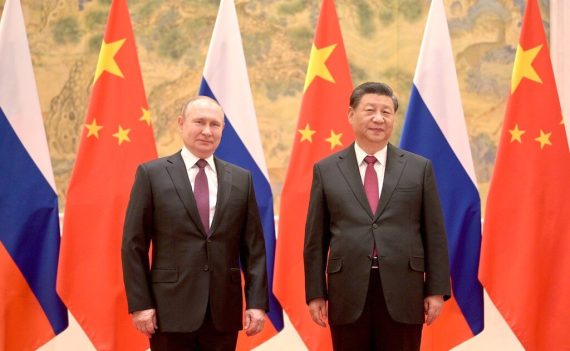

Amid escalating tensions between Moscow and the West over Ukraine, Russian President Vladimir Putin paid an official visit to China to finalize the negotiations over a new $80 billion natural gas agreement. On February 4, Gazprom signed an agreement with China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) to supply Russian gas to China via the Far Eastern route for the next 25 years, which will boost Russian gas volumes to China by an extra 10 billion cubic meters (bcm) a year.

Unlike the previous Russia-China gas agreement on the Power of Siberia pipeline, which is being built for the last five years, the new agreement does not entail the construction of an additional pipeline network. Although the Western media dubbed this agreement unexpected, the negotiations over the agreement lasted six years and resulted in the signing of memoranda of understanding in 2015 and 2017, respectively.

Russia has long aimed to capitalize on its vast hydrocarbon resources to cater to China’s increasing liquefied natural gas (LNG) demand. The agreement was signed at a time of an uneasy geopolitical situation between the U.S. and Russia over Ukraine, which prepares for the full-scale war with Russia. In this vein, it is significant that the new gas agreement was settled in euros in an effort by both Moscow and Beijing to diversify away from trade in U.S. dollars.

The de-dollarization process is a relatively new phenomenon in Russia-China trade relations, and can be seen as a move by both countries to enhance security of bilateral trade against potential U.S. sanctions. This process is more visible in the energy field with Gazprom and the CNPC mainly using national local currencies – ruble and yuan – and sometimes euros due to the current trade volumes between the EU and Moscow-Beijing. This move can also be explained by Russia’s and China’s desire to push for a greater role of their local currencies in the global financial market.

In addition to natural gas export, the new deal would boost the development of Russia’s Far East, which has remained economically underdeveloped for many years; help create more jobs; fully gasify the region; and attract additional investments.

Europe remains the top destination for Russian gas and oil as the volumes of exported energy are much higher than those exported to China.

Although the agreed extra gas volumes are moderate for China, the biggest natural gas consumer globally, Moscow seeks a deeper alliance with Beijing and to gain its political support aimed at neutralizing the Western pressure and possible new economic sanctions. The new gas deal raised concerns in Europe that Moscow would sharply divert its LNG exports to China; however, the LNG export to China will not flow through Russia’s European pipeline network. In other words, Europe remains the top destination for Russian gas and oil as the volumes of exported energy are much higher than those exported to China, and hence Moscow is unlikely to decrease the volumes of LNG to Europe anytime soon.

Apparently, with this new contract, Russia will strengthen its monopoly in the Chinese energy market and monetize gas production in the Sakhalin region.

Although the new energy deal will bring certain dividends to Russia, it cannot count on China’s deep involvement in the Russian-Western standoff over European security. China’s restrained position over the Ukraine crisis as seen in the general statement to “resolve differences through dialogue and consultation” bolstered speculations that the possible invasion of Ukraine would serve as a precedent for Beijing’s military attack against Taiwan.

Although the new energy deal will bring certain dividends to Russia, it cannot count on China’s deep involvement in the Russian-Western standoff over European security.

Indeed, the Chinese authorities see some parallels in the Ukraine crisis and their reclaim of Taiwan, but it is unlikely that China would welcome a full-scale war in Europe, as any upheaval could jeopardize its economic interests in the region. In the last several years, China has cultivated commercial interests in Ukraine, including defense industry and critical infrastructure within the framework of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and hence would be unlikely to welcome hostilities in this country.

Moreover, China deliberately avoids any possible military confrontation with the U.S. or NATO, and relies on its rising economic power as a tool. Therefore, a possible invasion of Ukraine by Russia may result in global economic disruptions and negatively affect China’s economic stability during the post-pandemic recovery period, as well as the running of Chinese companies. However, both China and Russia have an interest in deepening their political and economic ties in an uneasy period when both are cautious of Washington’s bellicose rhetoric.

Whereas recent events, such as the Russia-China-Iran joint naval exercises, intensifying incursions of Chinese jets into Taiwan’s airspace, and the harsh Chinese statements towards Taiwan, stir concerns in Europe of Moscow and Beijing creating a simultaneous crisis in both Europe and the Indo-Pacific region so as to undermine Western influence and earn additional concessions, this scenario is unlikely under the current conditions.

In contrast to Russia, which is a declining power with a one-man rule and a stagnating economy, China has long been revising the international order through its soft power methods and existing global institutions, thus preserving its global reputation. Given this fact, it is safe to note that the Chinese army will unlikely commit a blatant violation of international law to seize Taiwan, though it definitely possesses the capacity of destabilizing regional security.

What is more, unlike Ukraine, Taiwan enjoys the paramount support of the U.S. militarily, politically, and economically, and a possible invasion of Taiwan would bring an unprecedented reaction by Washington causing severe economic, political, and security damage to Beijing. In this case, even the close alignment with Russia will not yield significant results.

China may look as a reliable partner but always remains tightfisted when it comes to taking high risks, and expresses carefully worded support for Russia. It is most likely that the Chinese will attempt to dissuade Russia from invading Ukraine, but, at the same time, the country feels comfortable with an economically weak and internationally isolated Russia. The current standoff will likely help China secure.

Recommended