The U.S. administration under Joe Biden has singled out a “growing rivalry with China and Russia” as a key challenge facing the United States. A White House document outlining Biden’s national security policies, made public on March 3, 2021, describes China, the world’s second-largest economic power, as “the only competitor potentially capable of combining its economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to mount a sustained challenge to a stable and open international system.”

The 24-page document also warns that Russia “remains determined to enhance its global influence and play a disruptive role on the world stage.”

According to the document entitled “Interim National Security Strategic Guidance,” both Beijing and Moscow “have invested heavily in efforts meant to check U.S. strengths and prevent us from defending our interests and allies around the world.”

After four years of former president Donald Trump’s “America first” approach, Biden has vowed to confront “authoritarianism” in China and Russia while reengaging with allies and centering multilateral diplomacy.

Washington and Beijing are at odds over influence in the Indo-Pacific region, China’s economic practices, and human rights in Hong Kong and the Xinjiang region.

Moscow’s relations with Washington are at post-Cold War lows, strained by issues including the conflicts in Syria and Ukraine, Russia’s alleged meddling in elections in the United States and other democracies, and the poisoning of Kremlin critic Alexei Navalny.

Actually, this is not the first time a Democratic U.S. administration vows to shift its emphasis away from unneeded legacy platforms and weapons systems to free up resources for investing in cutting-edge technologies to contain China’s increasing and widening influence not only in Asia, but also in the Middle East and Africa.

Hillary Clinton, the secretary of state in the Obama administration, openly described Washington’s new foreign policy as “America’s Pacific Century” in an article she wrote in 2011.

Clinton believed the future of politics will be decided in Asia, not Afghanistan or Iraq, and the United States will be right at the center of the action.

But as the U.S. Asia strategy unfolded, Chinese perception has changed and Beijing began to see the rebalance toward Asia as a shift of focus from economic and diplomatic engagement to one more centered on security issues. The concern peaked in the fall of 2011, when the U.S. decided to push the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in which China is not a member, as a top priority of its trade agenda. Washington also announced its rotating military deployment of U.S. Marines Corps in Australia and tried to insert a security agenda into the East Asia Summit.

In response to the U.S. application of more diplomatic, security, and economic resources to Southeast Asia, in part to undermine China’s growing influence, China has stepped up efforts to strengthen ties with ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) countries, especially Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, Indonesia, and Malaysia. Beijing also moved to enhance its economic cooperation with South Korea, Japan, India, Australia, and New Zealand.

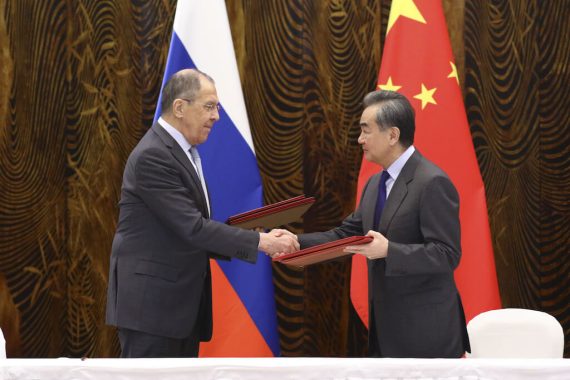

A mighty obstacle: Growing China-Russia cooperation

China’s most important response was to enhance and deepen its relations with Russia, another U.S. rival and one that the U.S. has tried to contain since the Cold War. Both Beijing and Moscow strengthened their economic and military relations to counter Washington’s sphere of influence in the region.

Today with the deepening ties between China and Russia, the Biden administration faces a worst-case scenario that could prove to be the most significant test of Biden’s leadership.

In April 2021, Russia and China simultaneously escalated their separate military activities and threats to the sovereignty of Ukraine and Taiwan respectively – countries whose independence is an affront to Moscow and Beijing but lies at the heart of the U.S. and its allies’ interests in their regions.

VIDEO: US-China meeting breaks into tense confrontation on camera

Even if Moscow’s and Beijing’s actions do not result in a military conflict of either country, the scale and intensity of the military moves rises the concerns of the Biden administration officials. The U.S. and its allies do not dismiss the possibility that Russia and China are sharing intelligence, and the likelihood that they are increasingly coordinating actions and strategies.

The Annual Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community believes China is attempting to exploit doubts about the U.S. commitment to the region, undermine Taiwan’s democracy, and extend Beijing’s influence. It also warns about Russia’s growing strategic cooperation with China to achieve its objectives.

Biden’s defining challenge

In such a critical political and strategic environment, the Biden administration once again is trying to establish policies to face and dismiss the key challenges facing America. But the question is how will it do this. Will the U.S. target Russia first? Will Washington directly carry out policies to contain China? Or will it deal with China and Russia in tandem?

Around the shady corridors of the White House and the State Department, it is easy to see there is an ongoing debate on whether to start with Russia or China.

The tendency to assign different priorities to the two countries is understandable. Pivoting its foreign policy towards containing China has been the grand strategy for the U.S. for more than a decade. With its immense economic weight, world-class technological capabilities, swelling geopolitical ambitions, and growing global influence at a time of intricate U.S.-China economic entanglement, China poses an unprecedented strategic challenge that has to be carefully weighed.

Recommended

But Russia poses a more immediate threat with its aggressive actions in Europe, subversion of the U.S. alliances and alleged cyberattacks on the U.S. elections and infrastructure, while the United States’ negligible economic and political ties with that country allow a harsher Cold War-like response.

In Washington, some argue that the Biden administration should focus its attention almost exclusively on China because of the asymmetry in the nature of the China and Russia challenges. But the counterargument is that focusing exclusively on China would result in very little attention being given to Russia as a strategic actor, and would be viewed through the lens of the U.S. relations with China. Obviously, that would not prevent Russia from drawing closer to China and augmenting the power of the latter.

The question is will the Biden administration be able to define a policy to deal with China and Russia in tandem? And, will it choose to do so?

To carry out a policy of dealing with Beijing and Moscow at the same time, Washington must first recalibrate its policies towards its allies in Europe, the Middle East, and NATO. In other words, the Biden administration should start adopting strategic policies towards its allies to restore the damage caused by the short-sighted tactical decisions of the past.

Biden’s first official meeting in Brussels with NATO leaders could be a good start. However, Biden should once again think how the U.S. can hope to contain Russia and China when sanctioning allies in Europe and the Middle East. Biden should start accepting multipolar realities and start mending relations with allies in Europe like Germany, France, and Turkey.

The U.S. should find a common ground with its longtime NATO ally Turkey especially keeping in mind that Ankara’s relations with the Central Turkic republics – all of which are former Soviet republics – are improving at a fast pace after Azerbaijan liberated Nagorno Karabakh with Turkey’s political and military support. While Moscow has stated its discomfort regarding the increasing cooperation in the Turkic-speaking world, this could give a chance to the U.S. to find a path and a reliable partner in a region with direct borders with Russia and China.

At the same time, only repairing alliances and rallying support for the U.S. policy towards Russia and China will not suffice. To develop a coherent approach, considerable effort will have to be devoted to reconciling the different priorities and threat perceptions of the United States’ European allies with regard to Russia and China and their strategic alignment.

Of course, this may be a lot for Biden to handle. However, how deftly Biden addresses the combined, growing challenge from Russia and China will shape the new world order and Washington’s relations with its longtime allies.