The world is witnessing a dramatic revival of the 20th-century bipolar geopolitical order featuring the Soviet Union, today’s Russia, on the one side, and the United States on the other. This power struggle has shown one of its ugliest faces in Syria and now is showing itself in Eastern Europe with the Russia-Ukraine war. As we slowly leave the nightmare of the COVID19 pandemic behind, a new global tension is born with the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

But, there’s a region where this rivalry between the U.S. and Russia might be writing a new chapter: Latin America. Latin America is a competitive territory, abundant in natural and human resources, that could be the dream of any world superpower.

On February 3, the Colombian Minister of Defense Diego Molano stated, “We know that men and units of the FANB (Fuerza Armada Nacional Bolivariana) have been mobilized towards the border with technical assistance from Russia … and Iran.”

This happened amidst the tensions in the eastern Colombian region of Arauca, an enclave of borderline between Colombia and Venezuela, where clashes between the Colombian army and different subversive groups occur constantly and where in January alone at least 68 people were killed.

The day after, the Russian embassy in Colombia issued a statement condemning Molano’s statement as “irresponsible” and denying any involvement in military assistance to Venezuela that could harm Colombia.

But this was not the first time Molano makes a reference to Russia. In May 2021, Colombia was under one of the most turbulent revolts in the country when millions took to the streets to protest against the government’s handling of the pandemic, the critical social situation, tax reforms, and other essential issues.

Molano accused Russia of being behind cyberattacks against the Colombian government.

This extraordinary event, in a country where civil society used to be scared to raise its voice, shook the establishment and evidently made it unusually nervous. Molano then accused Russia of being behind cyberattacks against the Colombian government, an assertion immediately denied by the Russian government.

Colombia and Venezuela broke diplomatic ties in August 2018 when right-wing candidate Iván Duque won the election in Colombia, the strongest and most loyal ally of the United States in Latin America. This U.S.-Colombia relationship is mostly built around the war on drugs and the leftist guerrillas active in the country for the last seven decades.

In 2017, Colombia became the first and only “extra continental ally” of NATO.

Both Colombia and Venezuela have had very tense ties since Hugo Chávez came to power in Venezuela in 2002, while ties were absolutely cordial prior to then. This constantly stressful environment between the two brotherly nations – both of whom consider Simón Bolívar their founding father – might turn into a breeding ground for the Latin American version of the so-called clash of civilizations.

In 2017, then president Juan Manuel Santos, recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize in 2016, signed an agreement between Colombia and NATO in Brussels, whereby the country became the first and only “extra continental ally,” which according to the alliance would “develop cooperation with NATO in areas of mutual interest, including emerging security challenges, and contribute actively to NATO operations either militarily or in some other way.”

On December 8, 2021, Minister Molano signed another treaty with NATO turning Colombia into the first and only “global partner” in Latin America. The agreement’s purpose was to “improve our defense capacity” and to “articulate cooperation with allied nations.” This is something neighboring Venezuela didn’t receive well. Nor did its ally, Russia.

Sergei Ryabkov, deputy foreign minister of Russia, said that he would “neither confirm nor deny” the possibility that Russia might send military assets to Cuba and Venezuela.

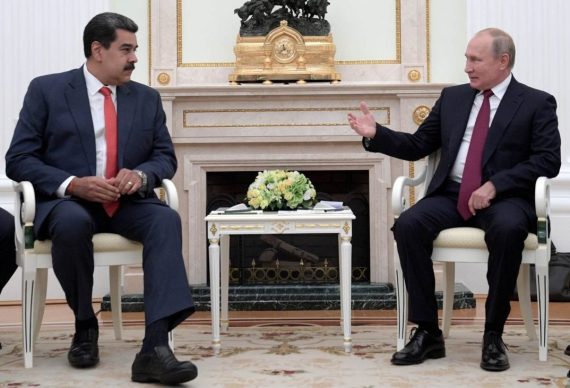

On the other hand, Venezuela has strong diplomatic, military, and economic ties with Russia. Since Hugo Chávez became president of Venezuela, both nations have entrenched their relationships. Now with President Maduro, these ties have deepened. On February 16 of last year, Maduro received Russian Deputy Prime Minister Yury Borisov in Caracas, and expressed Venezuela’s support for any Russian move on Ukraine.

The main issue discussed in the meeting was the strategic military cooperation between Russia and Venezuela. As a precedent, in January, Sergei Ryabkov, deputy foreign minister of Russia, during talks with his counterparts in the United States said that he would “neither confirm nor deny” the possibility that Russia might send military assets to Cuba and Venezuela if the U.S. and its allies do not limit their military activities in Latin America.

Recommended

Venezuela is estimated to have received around $17 billion in loans from Russia since 2007, spending an unknown but presumably considerable amount on the purchase of weapons from the Kremlin. In the oil industry, the main source of income for both states, Russia has played a considerable role by taking part in the trade of this commodity, finding clients that evade the U.S.-imposed sanctions on Venezuela, thus giving some oxygen to the South American nation’s fragile economy.

There are at least 20 areas of cooperation between Russia and Venezuela, mainly, energy, military, and transportation. Other countries, in the political orbit of Venezuela, like Bolivia and Nicaragua, also have good ties with Moscow. Cuba, the oldest Russian friend in the region, is no longer alone.

Is the United States losing its “backyard” in Latin America?

In light of this reality and Russian influence in Latin America, it is easy to guess that the United States may not be very pleased with the situation. Things may get even harder for the U.S. considering that in May this year, Colombians will elect a new president and leftist candidate Gustavo Petro seems the most likely to win. Petro maintains an approach based on resuming diplomatic ties with Venezuela. The Colombian people are increasingly reluctant to any form of confrontation with Venezuela and the popular support for Duque’s right-wing government is constantly seeing new lows.

VIDEO: Russian Expansionism under Vladimir Putin

The U.S. worries about the presence of countries other than Russia in Latin America – namely, Iran and China. Iran and China have been building stronger ties with Venezuela and other Latin American nations. Considering that countries like Chile, Mexico, Argentina, and Costa Rica have turned to the political left in the last few years, and that other regional giants like Colombia and Brazil may do the same soon, the task for U.S. diplomacy may require exerting more efforts in the years to come to assure that their eastern antagonists – the Russians – fail to conquer what they consider to be theirs. The Monroe Doctrine, which states that “America is for Americans,” could become obsolete in the decades ahead.

The fear of some Colombians and Venezuelans lies in what history has taught them: when empires fight, small nations suffer. Even though it is clear that the characteristics of Latin America are substantially different than those of the peoples of the Middle East or Eastern Europe, the textbook of empires has always been the same: find a puppet in a rich place, appropriate people’s wealth, conquer another wealthy nation, and let the locals be the ones whose blood spills.

Only time will tell if Latin America will become the next playground for mighty powers such as the U.S. and Russia, or if they find a third way that shields them from becoming history’s latest tragic example.