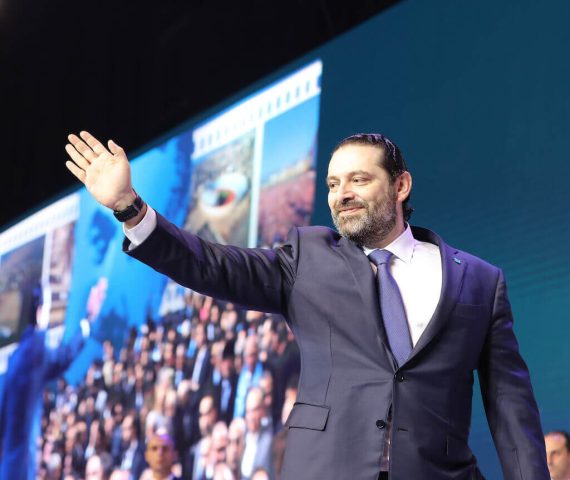

In a televised interview on the Iranian Al-Alam news channel on February 8, secretary general of the Lebanese militant group Hezbollah, Hassan Nasrallah, revealed that they wished the ex-Lebanese prime minister, Saad Hariri, reconsider his bombshell decision of “suspending” his political career, announced on January 24.

Nasrallah called the decision “unfortunate,” given that Hariri was their “candidate for the premiership,” highlighting that the political landscape remains extremely opaque in a post-Hariri era and that channels of cooperation and communication with the Future Movement, Hariri’s political party, shall remain open.

Ironically, Hezbollah never named Hariri for the premiership in the custom parliamentary consultations often held by the president of the republic before a PM is designated based on a majority of votes. However, Hezbollah’s position on Hariri’s departure says a lot about the role Hariri played to the militant group’s advantage especially since 2016, despite Hezbollah basking in unrivalled power during that period.

Hariri’s exit does not necessarily imply that observers, politicians, and researchers have written him off completely; however, his decision should not be taken lightly either, in terms of the seismic shift the country is undergoing by moving completely into the “Iranian influence archipelago.”

In late January, Saad Hariri arrived in Beirut following months of speculation in the wake of yet another solitary retreat – this time in the Emirati capital, Abu Dhabi – that came into effect mid-July last year. Hariri, a PM-designate at the time, stepped down after failing to form a government for over eight months. In Beirut, Hariri met with his aides, party members, MPs from his bloc, and other sectarian leaders or figures, and proceeded to announce the unthinkable: suspending his involvement in political activities and not running in the upcoming parliamentary elections.

In third-world countries (although I have reservations regarding the term), politicians and leaders do not simply step down: they either abdicate to their heirs or die while still in office. If they ever step down, it is often a form of a relegitimization process following serious blunders. Exhibit A is Egypt’s leader Gamal Abdel Nasser’s shenanigan in 1967 following his country’s catastrophic defeat by Israel in the Six-Day War of 1967.

Hariri is no Nasser

But Hariri is no Nasser and he might not even aspire to be one, and, Hariri was not met with waves of people flocking the streets asking him to rescind his decision as Nasser experienced back then. Hariri enjoyed a few flagship “selfies” with a handful of supporters near his Beiruti mansion and a couple of hours of chants in his name. The feeble reaction from Saad’s supporters, the ones he represents, is symptomatic of current times in Lebanon where sectarian leaders, previously holding gods-like statuses, are dealt major blows to their popularity, to a varying extent.

It indeed only required 24 hours for the narrative among decision-makers to shift: the question was no more about how to convince Hariri to come back as much as about who inherits his place and attempts to fill his once golden shoes.

The prospects of a Sunni boycott were immediately shelved with the country’s grand mufti, once a Hariri protégé, urging Sunni leaders not to follow Saad’s suit. Parallels between prospects of a Sunni election/politics boycott and the Christian precedent underscored in the 1992 boycott of the postwar parliamentary elections, were null and shortsighted. At the time, Christians were united and had a plan, while Sunnis today are completely disenfranchised and have lost their regional cover.

The question was no more about how to convince Hariri to come back as much as about who inherits his place and attempts to fill his once golden shoes.

As cliché as this might sound, “politics hates a vacuum” and with the current Lebanese socio-economic context, said vacuum is only to be filled with fear rather than hope, as the Canadian author and social activist Naomi Klein once stipulated. Allow me to explain why.

The Sunni community today stands at a three-way crossroad with different options to mitigate the current situation. As Saad fades into the horizon, until further notice, Sunnis can either succumb to further marginalization and disenfranchisement without devising a plan to attempt to fill Hariri’s shoes, or the main Sunni figures in the country can move towards creating a consortium that manages the transition into a post-Hariri era through cooperation, or lastly, compete amongst each other over the leadership of the sect causing further communal depression and the complete erosion of the sect’s leverage within the country’s power-sharing arrangement.

Unfortunately, Lebanon isn’t shifting into a secular state any time soon, nor will its sectarian system be altered at the moment, despite the hopeful dreams of the Lebanese youth that took to the streets during the October 2019 uprising.

It appears that the Lebanese Sunni leaders understand that now is not the time for petty politics amongst them, especially during an extremely sensitive phase where Iran sits and negotiates with the United States in Vienna not only regarding its nuclear program but also its influence in the region, and while the world is starting to show signs of reconsideration of policies towards the Syrian regime, despite its track record of war crimes and crimes against humanity.

As such, a common understanding seems to be brewing for the option of a concerted effort to rally the community and block the way in face of lackluster disbursement of Sunni votes. The cornerstone of such an effort will be the mufti who already adopted a proactive approach to the situation, in addition to the club of ex-prime ministers who, alongside Mikati, can throw their weight around.

However, this does not ensure that Hariri’s shoes will be filled. After all, and despite his blunders, he remains the Sunni community’s most popular leader and no other figure enjoys the potential Saad once represented – not even the sitting billionaire PM, Najib Mikati, who has yet to come out of his localized constituency in northern Lebanon towards the country as a whole.

With the Sunni community divided, Hezbollah can now rule much easier

The recent dynamics will pave the way towards a schism between the Sunni figures of the cities and those of the peripheries, who are not aligned in politics and allegiances. In fact, peripheral figures have a bigger chance for representation today, especially since they’ve maintained good relations with the Syrian regime in Damascus and with the tides shifting in their favor.

This schism will serve as a conduit for both Hezbollah and Bashar al-Assad to exercise influence over the Sunni role within the power-sharing arrangement, allowing them to break any form of unity sect leaders might work to establish. It’ll be easier for Hezbollah to rule in the wake of a divided Sunni community.

Recommended

Hezbollah has lost an ally in Saad Hariri, a pro-Western PM with access to all capitals of the world who acted as a buffer between the international community and the Iran-aligned militant group and also as a whipping boy for most of the shortcomings under the pretext that “Hezbollah doesn’t rule.” Now, the group is gearing for a wider share of the pie in Lebanon as the reconfiguration of spheres of influence is underway in the region.

Hariri is obviously jumping ship, a sinking one with more holes than the current 6.5 million population can fill even if they all chipped in.

Hariri’s decision stacks up against a series of mistakes he has committed over a 17-year period, yet the decision might eventually pay off during these trying times – as in now. Saad is obviously jumping ship, a sinking one with more holes than the current 6.5 million population can fill even if they all chipped in. The economy is in shatters, the country’s relations with the outside world are collapsing, and the predominant Hezbollah-Free Patriotic Movement alliance has no competency or potential to lead the country out of the abyss.

More so, in order to secure a deal with the International Monetary Fund and other global donors, the time will come where even more difficult austerity measures will be required with harsh reforms that often come at a popularity expense. Hariri being out of the picture means he won’t be associated with those measures and will spare himself further decline in popularity.

Lastly, Saad’s political hiatus might help him evade an eventual poisoned chalice requiring him to visit Assad in Damascus again. All those factors, alongside rumors suggesting that Hariri eventually also caved against the backdrop of regional pressure forcing him to step away from the Lebanese political scene, mean that his solitary retreat is poised to be an elongated one. Arab and more specifically Gulf countries, opening up towards the Syrian regime means that the person holding the job of Lebanese prime minister will have to change, and Saad is no longer the man for the job.

Back to Nasrallah’s interview, meant to celebrate the 43rd anniversary of the “victory of the Iranian revolution.” The most profound statement that is set to describe the state of affairs in Lebanon for the coming period came when Hezbollah’s secretary general claimed, “Speculation over a parliamentary majority is unnecessary, and there is still time for elections.

Parliamentary majority does not lead to fundamental change [in terms of who rules].” Meanwhile, it is important to ask the following question: Is Saad’s migration from Lebanese politics or the 215,653 Lebanese who left the country over the past four years as per Information International’s most recent report more consequential for the country?