A

nti-migrant racism in North Africa was thought to be a taboo, but in reality it never was. Racism against African migrants, coupled with unabashed anti-Black xenophobia, is alive and kicking in North Africa. Tunisian President Kais Saied’s recent comments on February 21 about sub-Saharan migrants surely shocked many people. Saied labelled migrants as “hordes” and a “demographic threat” to his country. Even more, Saied called for “the need to put a rapid end to this immigration,” which, to his view, has become a source of “violence, crime and unacceptable acts.”

For a country like Tunisia, a generator of migrants fleeing to find a better life in Europe, Saied’s speech may seem out of place and contradictory. Doesn’t the European far right, which applauded Saied’s speech, say the same about Muslim migrants?

President Saied’s invective is neither unprecedented nor isolated in the larger geographical area, the Maghreb. From Morocco to Libya, passing through Mauritania, Algeria and, of course, Tunisia, hateful allegations are not only the prerogative of what some people there call the “little people” to whom we could add the “uncultured” or the “intolerant.” In the upper echelons, at the highest level of the Maghreb states, the same ideas circulate.

For this discourse is not new. Since the Maghreb became the exit door for migrants from Africa to reach the fabled El Dorado, Europe, this immense territory has been transformed into a huge waiting room for tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of sub-Saharan migrants unable to reach the European coast. A waiting room that has turned into an open-air prison over time. Especially since, to curb this migration flow, the European Union outsourced its borders and entrusted their guarding to the Maghreb states by rewarding them financially, diplomatically, or both.

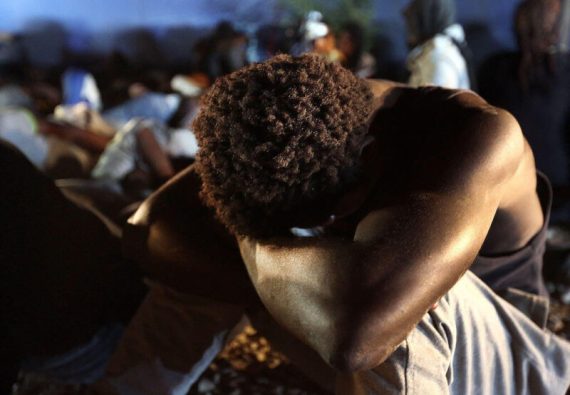

A migrant mass

The direct consequence of this strong policy of containment has been the creation of a migrant mass that has settled permanently in the Maghreb and lives on the fringes of society, waiting for a passage to Europe. It has also caused inevitable impoverishment and generated the phenomenon of criminalization that no one questions, especially not the local population in contact with migrants.

It is important to understand that as long as migrants were only crossing the territory, they were tolerated. It was only when they were prevented from doing so that their presence began to pose a problem and the old demon of racism resurfaced.

Over the past twenty years, many serious and sometimes bloody incidents have taken place against migrants in North Africa, without being properly reported by the press. Police raids followed by robberies and humiliations, assaults, lynching organized by neighborhood lords or angry citizens, and even rapes have targeted this vulnerable population.

Racism is as old as the world and knows no borders. The Maghrebi expressions for Black people, “âzzi” (black), “kahlouche” (negro), “âbid” (slave), or “oussif” (slave, servant), which have been heard with force recently, are not new and are not a relic of colonialism. As far back as the 14th century, Ibn Khaldun, a historian of Arab descent born in Tunis, wrote that “the only peoples who accept slavery are the negroes, because of their lower degree of humanity, their place being closer to that of the animal.”

Legacy of French colonization

These expressions are therefore the fruit of a mentality that predates the French colonization of Algeria and Mauritania, the French protectorates of Tunisia and Morocco, and the Italian occupation of Libya. What has changed is the violence of words and actions.

In 2012, the Moroccan weekly Maroc Hebdo devoted an entire dossier to the “Black Peril,” attacking without embellishment those who “live by begging, engage in drug trafficking and prostitution” and “pose a human and security problem for the country.” On Moroccan social media, there are regular calls for the expulsion of African migrants, the closure of borders, and the banning of mixed marriages in order to preserve an improbable “purity of the Moroccan race.”

On the other side of the border, in Algeria, a hashtag on Twitter resurfaces from time to time (in Arabic), #NotoAfricansinAlgeria, which immediately sets the world on fire by calling for the hunting down and deportation of migrants. Sometimes, the creators of these hateful messages deliberately confuse Black migrants with Black North African citizens. From the Atlantic Ocean to the Egyptian border, there is a Black Maghrebi population whose ancestors were slaves or settled in North Africa several centuries ago. They are certainly citizens, but they are still considered second-class ones.

A few years ago, in 2016, a Black model of Algerian nationality, Amina Hamouine, had to face an extraordinary campaign of hatred because she had the idea, or the “bad idea” as her detractors would say, of being photographed wearing a Kabyle dress—the Kabyle people are Berbers from the region of Kabylia. This was an unforgivable mistake for those who identify the Kabyle woman from the whiteness of her skin.

Too Black?

Recently, Khadidja Benhamou, an Algerian citizen from Adrar in the south of the country, was deemed “too Black” to wear the crown of Miss Algeria 2019—her skin color did not represent all Algerians, it seems.

But it is not only the “little people” who indulge in these feelings that sociologists and anthropologists call “systemic negrophobia.” Some Algerian leaders do as well. In 2017, five years before the Tunisian president’s remarks, senior officials of Algiers, which has a virulent anti-colonial past, were not kind to migrants either.

Ahmed Ouyahia, an Algerian politician who has been appointed prime minister ten times—an absolute record— and who at the time was head of President Abdelaziz Bouteflika’s cabinet as a minister of state, described African migrants on the private television station Ennahar TV as “[t]hese illegal foreigners bring[ing] crime, drugs and several other scourges.” At the time, Ouyahia was the secretary general of the National Democratic Rally (RND), one of the two crutches, along with the National Liberation Front (FLN), that support the government in Algeria.

His words were echoed and amplified a few days later by Algerian Foreign Minister Abdelkader Messahel, who identified the arrival of sub-Saharans in the country as a “threat to national security.”

But the ultimate horror was reached again in 2017 in Libya, when footage filmed by CNN journalists revealed to the world the unimaginable in the 21st century: an auction of migrants from Nigeria at a market near Tripoli.

Racist rhetoric

These migrants were considered “âbid,” slaves, and as “slaves” they were subjected to the violence of deprivation of freedom and control over their own body. The case created a considerable stir around the world, but not in Libya, where few are unaware of the atrocious end of Colonel Gaddafi’s Black guards, composed of Chadians, who were mobbed and lynched during the 2011 revolt. It is also true that these praetorian guards had a bad reputation as they were identified with the murderous excesses of the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya (republic).

In the rest of the Maghreb, while violence does not reach this frightening degree, it is no less present. In 2013, a Senegalese man was murdered near a bus station in Rabat, the Moroccan capital, over a petty dispute about a seat on a bus. In 2014, in a neighborhood of Tangier, a large city in northern Morocco, another Senegalese citizen was killed and four other migrants were injured in a machete and knife attack.

Young Moroccans staged an attack against an apartment occupied by migrants to show them that they are not welcome in a region where they are nicknamed “Ebola,” after the viral disease, and are “tropical” according to the popular imagination.

The same is true in Algeria, where in 2016 another violent pogrom targeted migrants passing through Ouargla, in the center of the country, after the murder of an Algerian by an undocumented Nigerian. The crime of one was seen as the crime of all, as migrants are synonymous in the collective consciousness with misdemeanor. In the previous year, an illegal migrant of Cameroonian nationality was the victim of a gang rape in Oran in northwest Algeria—a crime committed by Algerians, in other words, by North Africans.

The above was similar to the stabbing of three Congolese students in the center of Tunis in 2016, the violent beating of an Ivorian citizen in the suburbs of the Tunisian capital, the assassination of the president of the association of Ivoirians in 2018, and other major incidents. All committed by Tunisians, once again, North Africans.

Anti-racism laws

To counter this unfortunate litany of racist acts, Tunisia passed a law in 2018 penalizing racism and established January 23 as the “National Day for the Abolition of Slavery.” However, the 2018 law, historical, innovative, and the first of its kind in the Arab world, was annihilated by the verbal outrage of President Saied on February 21, 2023, when he evoked a “criminal plan prepared at the beginning of this century to change the demographic composition of Tunisia” and whose objective was to transform the country into an “African-only country” and to remove its “Arab Muslim” identity.

Of course, one can try to nuance this reality by recalling, for example, the decision of the Moroccan authorities to launch campaigns to issue resident permits, such as in 2014, which initially resulted in the regularization of 25,000 undocumented migrants. It can also be argued that, like Tunisia, Algeria adopted a law criminalizing racial discrimination in 2020. But these gestures of goodwill have little impact if they are not followed by campaigns to educate the local population on the need to accept the “other.” Campaigns that television stations refused to broadcast, as was the case in Morocco.

All crises, whether economic or security-based, produce exasperation that ends up finding a scapegoat, and African migrants have become the ideal candidates. They pay for the economic crisis and the criminal behavior of a minority in their own community.

As a scapegoat, they also pay the price for some of the services rendered by the Maghreb states to Europeans: to showcase its status as a paid gendarme of the European Commission, Morocco got carried away by its destructive zeal on June 24, 2022, when it violently curtailed an attempt by several hundred migrants, mostly Sudanese, citizens of a “brotherly Arab” country, to force their way into Ceuta, a Spanish enclave on Moroccan territory.

Recommended

EU responsibility

The result—24 dead according to the Moroccan authorities, 37 according to a local association, not counting the missing—has not only tarnished Morocco’s image in Africa but also revealed another problem that is worth studying. In which state in the world, except for the former East Germany and the now defunct Berlin Wall and migrants escaping war to Greece and Italy, are dozens of people killed to prevent them from leaving a country that is not theirs to seek refuge elsewhere?

A tragedy that ended with a congratulatory gesture worthy of the former East Germany, as the president of the Spanish government, Pedro Sánchez, praised the brutal intervention of the Moroccan police force.

Finally, the European Union’s migration policy, which consists of preventing human beings from moving freely, by force if necessary, has helped this local outbreak of racism and intolerance, and dynamited several principles, some of them religious, that were thought to be immutable.

Pan-Africanism, the egalitarian and anti-slavery utopia propagated in most of the post-independence Maghreb countries, especially Algeria, has come to an end. The myth introduced by these countries of an integrating Islam that makes no distinction between a white and a Black person has been shattered. Despite many migrants adhering to Islam, they are treated as strangers to the Ummah.