A

lexandroupolis is a port city in Greece, known as “Dedeağaç” in Turkish. Back in the nineteenth century, this small town was located on the transportation and trade routes of the Ottoman Empire. Under the Greek administration, Alexandroupolis, which lies in the north easternmost part of the country, did not make a breakthrough for about a century. However, due to the developments in the energy sector and the changing security perceptions in the West, today, the city is emerging as a vibrant hub.

Energy transmission capacity

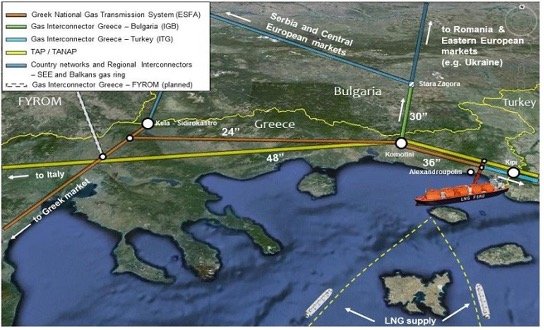

Alexandroupolis brings together a highway, railway, and airport network stretching from the Aegean Sea to the Black Sea. The highway and railway are directly connected to the port, and Alexandroupolis is also the connection point of TAP and TANAP, two major pipelines of the Southern Gas Corridor.

More recently, the Alexandroupolis Independent Natural Gas System (INGS), which includes both LNG storage with a capacity of 170,000 m3 and a regasification unit with a capacity of 5.5 billion m3, was constructed. The Alexandroupolis Floating Storage and Regasification Unit (FSRU) will be stationed 17.6 km southwest of Alexandroupolis at a depth of 40 m in the Thracian Sea.

The energy brought from the FSRU will be transmitted to the National Natural Gas System (NNGS) and distributed to consumers in Greece via power plants being built across Western Thrace. North Macedonia- and Bulgaria-linked companies are making investments to carry the energy via interconnectors to their own countries.

With the LNG terminal, planned to be built by the end of 2023, the Alexandroupolis port has the potential to become an energy hub. A plan to expand its capacity has been prepared by the port authority with the support of the Greek government. This includes a new electric rail line connecting the port to the Trans-European railway, the addition of much more quay space, a new cargo terminal, an additional 500-meter pier, and a bypass to the local highway.

Greece will make significant economic gains not only from the port and FSRU, but also from carrying the LNG as it holds more than 22% of the global LNG carrying capacity. With an interconnector extended into Bulgaria from TAP’s processing facilities in Komotini, and another from Sofia to Niš, gas will be transferred into Bulgaria and Serbia. Thus, a non-Russian gas option will be born in the region.

Greece’s Alexandroupolis policies

Alexandroupolis’s potential for the transmission of energy is strongly linked with Greece’s policies to be the key country in Europe’s energy security. To this end, Greece strengthens its diplomatic ties with both energy-exporting Gulf countries and importing European countries.

The Greek authorities’ rhetoric reveals that Greece aims to compete with Turkey’s role as an energy hub. At a recent meeting, Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis and Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman signed important agreements on energy. Prince Salman stated that Saudi Arabia is interested in hydrogen energy and making Greece a hub for hydrogen energy in Europe.

In his statement after the agreements with Saudi Arabia, the Greek Minister of Development and Investments Adonis Georgiadis claimed that Greece has very close strategic relations with Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Israel, and added, “What a great foreign policy the Turks have had for all these years, the opposite is happening now. Turkey is completely isolated and the biggest player in the region is undoubtedly Saudi Arabia, with which Greece has the strategic relationship I mentioned above.” Such developments are not only limited to Saudi Arabia.

As soon as Turkey and Israel declared that they were going to normalize diplomatic ties and reappoint ambassadors, Mitsotakis paid a visit to Qatar which is considered a geopolitical ally of Turkey. In the meeting, Mitsotakis, by pointing out that Qatar is a natural gas producer, mentioned the importance of Greece, especially Alexandroupolis, in energy transportation. More recently, President of the United Arab Emirates Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed met Mitsotakis as part of his visit to Athens. In the meeting, Mitsotakis briefed Zayed on the infrastructure facilities being built in Greece for LNG import, storage, and regasification. He claimed that these efforts, combined with Greece’s strategic geographical location, make the country an energy hub for the Middle East and a bridge connecting the East to Europe.

U.S. interest in Alexandroupolis

Alexandroupolis saw several development projects worth 2.3 million euros in order to reach the capacity to serve Arleigh Burke-class U.S. destroyers. In the context of NATO and U.S. military shipments, numerous military vehicles were delivered through the port. These include Black Hawk, Apache, Sikorsky, Chinook, and Romeo helicopters, and M1 Abrams tanks. Only in the summer of 2022, 2,400 pieces of military equipment passed through the port, making this the largest number of U.S. weapons ever to pass through a single port.

Numerous other mechanized units were reported to have been sent to the port, some of which were then sent to the islands that Turkey claims should be demilitarized. In the first stage, the claimed intention by Greece and the U.S. was to transfer them to Ukraine. In addition to arms transfers, in the context of Operation Atlantic Resolve, the U.S. Army 3rd Armored Brigade Combat Team with 4,000 soldiers and 2,000 pieces of equipment deployed in the region. U.S. jets were sent to Alexandroupolis to replace those is Larissa.

Moving beyond NATO, in 2019, the U.S. provided funds for the dislodging of a sunken dredger ship from the port basin. This provided access to the full capacity of the port and opened the possibility of serving large vessels. In the same year, Greece and U.S. signed a protocol which extended the scope of the 1990 Greece-U.S. Defense Cooperation Agreement and provided the United States access to the Alexandroupolis port.

In 2020, the U.S. Congress released funds for the installation of precision approach radars (maritime domain awareness) throughout the Aegean Sea. Consequently, Alexandroupolis came to the agenda in terms of Greece-U.S. cooperation before the Russian invasion of Ukraine. However, the Russian-Ukrainian war accelerated the port’s development attempts and provided a legitimate explanation for the policies being carried out in the port.

On the other hand, the privatization of the Alexandroupolis port is on the agenda, and two of the four candidates planned to participate in the tender have ties to Russia. Considering that the Port of Piraeus is operated by a Chinese state-owned company and the Port of Thessaloniki is operated by Russia-backed companies, Greece maintains its relations with non-Western powers too. Knowing the U.S. and European sensitivity toward Alexandroupolis, Greece may use these two candidates as a trump card to obtain potential U.S. or European aid under the excuse of aligning foreign policy objectives.

Fruits of lobbying

Greece’s initiatives in Alexandroupolis are supported by the Greek, Armenian, and Jewish lobbies in the United States. A report published by the Jewish Institute for National Security of America (JINSA) focuses on Greece, particularly Alexandroupolis, in all seven solutions it proposes for resolving the energy crisis created by the Russia-Ukraine war. The report emphasizes the importance of solidarity between the Greek Administration of Southern Cyprus (GASC), Israel, Egypt, and Greece. In this context, the report calls for the U.S. to take the financial and diplomatic leadership in the axis of the Three Sea Initiatives to develop the railway and road infrastructure of Alexandroupolis and increase defense aid to Greece. In the report, there is no mention of Turkey, NATO’s easternmost corner.

Moreover, in an interview with the Greek daily Kathimerini, Jonathan Rue, director of foreign policy at JINSA, explained his perspective with the statement that Turkey has deliberately abandoned its traditional role as NATO’s southeast anchor against Russia and other threats and that Alexandroupolis, bypassing the Turkish Straits, became an important alternative to Turkey in securing a position for the NATO forces in the region.

Meanwhile, Greek lobbying efforts appear to have borne fruit as witnessed in the statements of Bob Menendez, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, who recently paid a visit to Alexandroupolis and gave a statement claiming that the port has unlimited possibilities for Greece and its allies. He also claimed that Turkey, a NATO member, is the biggest threat in the Eastern Mediterranean.

The U.S.-Turkey-Greece triangle

The developments in Alexandroupolis coincide with the U.S. viewing Turkey as an unreliable actor in relation to Russia – even as a “security threat,” according to Menendez. This further coincides with the timing of Greece becoming a U.S. backup plan for replacing Turkey. As an answer to the rapprochement between Moscow and Ankara, for some time now, Washington has been counterbalancing Turkey by supporting Greece. Moreover, the Russia-Ukraine war has exposed the importance of the passage to the Black Sea.

Turkey has full jurisdiction over the Turkish Straits, thanks to the Montreux Convention, and has the right to close the straits during a war. In that case, Alexandroupolis is an alternative for access to the Black Sea, bypassing the Turkish Straits.

Regardless of their actual purpose, the American bases in Greece, from Crete to Alexandroupolis, are viewed by Ankara as some sort of encirclement. What is more, the amendment of the Mutual Defense Cooperation Agreement between Greece and U.S. gave the U.S. the authority to use the naval base in Souda, Crete, the Stefanovikeio Air Base, the Litochoro Training Ground, the Georgula Barracks in Volos, and the Yannuli Barracks in Alexandroupolis. This has led Turkey to question why and against whom the U.S. proceeded with the extension of its bases in Greece. This line of reasoning was further enhanced when the U.S. temporarily removed its arms embargo on the Greek Administration of Southern Cyprus.

Ankara’s perception is aggravated by the Greek side’s provocative rhetoric. As a check against Greece’s expansionist ambitions in the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean Seas, Turkey has long warned against the Greek extension of its territorial waters in the Aegean Sea and the militarization of the Aegean islands. Greece responds to Ankara’s policy by portraying Turkey as the expansionist side, and alarming the U.S. and the EU on so-called Turkish aggression.

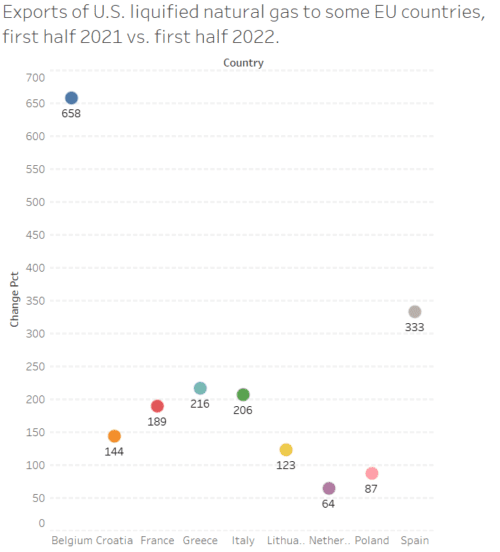

In doing so, Greece points out that Turkey cooperates with Russia in the defense industry and in terms of economic relations, portraying Ankara as NATO’s black sheep. While pushing for Turkey’s isolation within the Western bloc, Greece seeks to receive U.S. support in its claims regarding the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean Seas. Greece’s ultimate goal is to maximize the gains rooted in the momentum. In the case of Alexandroupolis, the increasing importance of LNG due to the embargos on Russian gas and the decline in U.S.-Turkey relations has resulted in the development of the city into an energy hub and a center for American military deployment.

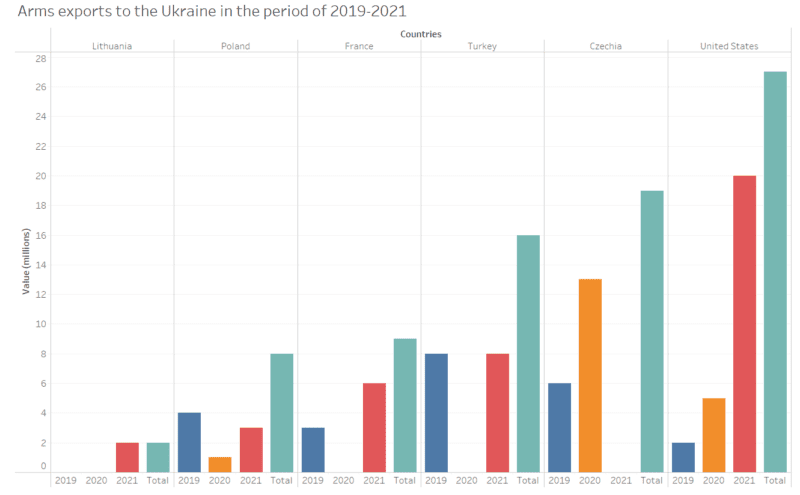

However, Turkey’s position on the war in Ukraine is very clear: Ankara supports Ukraine both diplomatically and through the supply of military equipment. Ankara has supplied almost 20% of military imports to Ukraine in the period 2019-2021 – a number that speaks for itself on Turkey’s position.

On the other hand, the improvement of relations between Moscow and Ankara is a response to the U.S. refusal to sell air defense systems to Turkey which resulted in Turkey’s purchase of the Russian S400s missile defense system. Thereafter, Turkey’s exclusion from the F-35 joint production program and the U.S. Senate’s negative approach to the modernization of Turkey’s current F-16 fleet and the purchasing of new F-16s as well as spare parts complicated the country’s defense ties with the United States. Turkey occasionally shows the U.S. that it is not without alternatives: when Hulusi Akar, Turkey’s Minister of National Defense, visited the U.K., his picture alongside the U.K.’s Eurofighter Typhoon was shared – a response to the U.S. Senate’s first negative decision on the F-16s, which was later changed.

Ultimately, the Turkish-Russian rapprochement is related to Turkey’s traditional active neutrality policy. The mechanisms of relationship-building are not the same as in the past and are highly influenced by Erdoğan and Putin’s exclusive mutual relationship; however, this doesn’t change the fact that NATO is indispensable for Ankara, as well as the other way around. Maintaining the ongoing relationship with Russia is not a major policy shift for Turkey. Ankara plays the game in accordance with the rules of a multipolar world. So, Turkey is neither anti-West nor pro-Russia – this has been Turkey’s regional geopolitical approach for some time.

Recommended

Notwithstanding, Putin recently announced a plan to turn Turkey into an energy hub for Europe. Erdoğan stated that Thrace in Turkey is the most suitable hub in the region. These developments might be read as the footsteps of an upcoming alternative to Alexandroupolis in Turkish Thrace. The overbalancing of Greece vis-à-vis Turkey is reciprocated by Russia with an increasing interest in Turkey which in turn leads to more provocative rhetoric from the Greek side. This, eventually led the situation to an impasse. Thus, U.S. decision-makers should consider the fact that they may be pushing Turkey toward Russia. The dispute which started with the U.S. refusal to sell military equipment to Turkey, today, has resulted in the U.S. selling more LNG to Europe and having an alternative access to the region. However, whether these gains are worth losing Turkey as an ally is open to question.